From Our Archives

Debie Thomas, The Gift of Rest (2021); Debie Thomas, Rest a While (2018); Debie Thomas, Come Away with Me (2015).

For Sunday July 21, 2024

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Psalm 89:20–37 or Psalm 23

Ephesians 2:11–22

Mark 6:30–34, 53–56

This Week's Essay

Four months ago in March, my wife and I joined a dear friend in "sitting shiva" for her deceased father. Shiva is the seven-day Jewish period of mourning when friends and relatives gather to remember their loved one who has died. It's a formalized way to process grief and to offer comfort, through ritual, liturgy, Scripture, prayer, and story-telling. There were about sixty of us in the Zoom room to share tears of laughter and sorrow.

Half way through the service, I experienced a jolt when we recited together Psalm 23 for this week, that most beloved of all passages in Scripture: "The Lord is my shepherd, I shall not want, He makes me lie down in green pastures. He leads me beside quiet waters and restores my soul." If I had shut my eyes on that Zoom call, I could have easily imagined myself worshipping in any church in the world. How remarkable, I thought, that this Jewish service should be so "Christian."

As I reflected on Ephesians 2:11–22 for this week, I had a brilliant glimpse of the obvious. And upon further reflection, I also realized how tragically typical my thinking was, and how thinking like mine across the last two millennia has led straight to anti-semitism. Reciting Psalm 23 did not make my friend's shiva "Christian." No, the opposite was true — my Christianity was Jewish. Jesus was a Jew. Duh.

As a Gentile, I had it backwards. Christians are not the "we" and Jews "them." It would be more theologically accurate for Jews to see themselves as "us" and Gentiles like me as "them." That, in essence, is what Paul tells the Gentile believers in Ephesus. And he extends this logic, and goes much further, rejecting all such us-against-them rhetoric and we-they antagonisms in favor of one new and harmonious humanity.

The Old Testament text for this week makes a clever and important play on words. We read how King David, who enjoyed his own regal "house" (= palace), wanted to build a "house" (= temple) for Yahweh. But that was not to be. Instead, Yahweh would build a "house" ( = dynasty) for David: "When your days are over and you rest with your fathers, I will raise up your offspring to succeed you, who will come from your own body, and I will establish his kingdom. He is the one who will build a house for my name, and I will establish the throne of his kingdom forever… Your house and your kingdom will endure forever before me; your throne will be established forever."

|

|

God covenants to make Abraham a father of many nations, Marc Chagall, 1931.

|

The Psalmist for this week repeats this Davidic promise: "I will maintain my love to David forever, / and my covenant with him will never fail. / I will establish his line forever, / and his throne as long as the heavens endure" (Psalm 89:28–29). The first story-tellers of Jesus go to great lengths to identify these Davidic promises with Jesus himself. He is the long-awaited Jewish messiah and Son of David. He inaugurated the forever kingdom.

All of the first followers of Jesus were, quite naturally, only Jewish. Most people in the decades after the death and resurrection of Jesus construed his followers as a sect of Judaism, which in fact it was. Even the so-called anti-semitism in the Gospels, says Paula Fredriksen in her book Augustine and the Jews (2008), is a misleading anachronism. Horrendous anti-semitism would come later, but initially, says Fredriksen, the denunciation of Jews by fellow Jews in the gospels is a type of "fraternal name calling" within Judaism. The acrimony and denunciations, she says, "were one of the most unmistakably Jewish things about the Jesus movement."

But bit by bit and across the years, as already foreshadowed in the Gospels themselves, Gentiles began to follow Jesus. Recall the pagan magi who worshipped baby Jesus, the Samaritan woman at the well, the Roman centurion, the man with the unclean spirit in Mark 5, the Syrophonecian woman, and the physician Luke. Recall too how Mark explained Jewish customs about ritual purity to his Gentile readers in order for his story to make sense to them.

This raised an obvious question. How was this even possible? How could impure and unclean Gentiles fit into the Jewish story of salvation? In his remarks to the Gentile believers at Ephesus, Paul uses the most unflattering language to describe the dilemma of the Gentiles. Just remember, he says, you uncircumcised Gentiles were "separate from (the Jewish) Christ, excluded from citizenship in Israel, foreigners to the covenants of the promise, without hope and without God in the world." Gentiles, he says, are "far away" in space and time to the Davidic promise of salvation that was fulfilled in Jesus.

|

|

King David, stone stele, by Marc Chagall.

|

Paul uses a different metaphor to make this point when he writes to the Gentile believers in Rome. The Jews are "natural branches." Gentiles are "a wild olive shoot" that has been "grafted in among the others and now shares in the nourishing sap from the olive root" (Romans 11:17). "You (Gentiles) do not support the (Jewish) root, but the root supports you." Or as Jesus himself bluntly puts it to the Samaritan woman at the well, "salvation is from the Jews" (John 4:22). Gentiles do well to remember their honorary, guest status.

It's no wonder that Paul describes the inclusion of Gentiles as a mystery. "This mystery is that through the (Jewish) gospel the Gentiles are heirs together with Israel, members together of one body, and sharers together in the promise in Christ Jesus" (Ephesians 3:6). Gentiles who were "far away" have been "brought near" in Jesus. The foreigners have been made fellow citizens, the aliens have been adopted into God's family.

And so Peter's shock in Acts 10–11 about acceptance of the Gentiles — "God has shown me that I should not call any person unclean;" and in Acts 15 the consternation of the Jewish followers of Jesus upon hearing that Gentiles were converting — should those Gentile converts be required to follow the law of Moses?

Paul summarizes the meaning and message of Jesus in a single word: "He himself is our peace." Beyond the many antagonisms of religion, ethnicity, race, class, and gender (we could extend this tragic list), Jesus "made the two one and has destroyed the dividing wall of hostility. His purpose was to create in himself one new man out of the two, thus making peace, and in this one body to reconcile both of them to God through the cross, by which he put to death their hostility" (Ephesians 2:14–18).

In the mission and message of Jesus, hostilities have ended, peace has come. Writing from Rome, the theologian Justin Martyr (c. 100–165) summarized this movement from hostilities to peace: “We who once took most pleasure in accumulating wealth and property now share with everyone in need; we who hated and killed one another and would not associate with men of different tribes because of their different customs now, since the coming of Christ, live familiarly with them and pray for our enemies.”

|

|

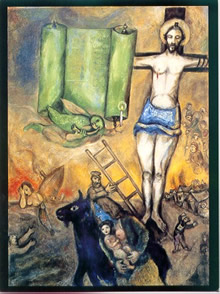

Marc Chagall, "Yellow Crucifixion" (1943).

|

Such is the radically egalitarian standing of all humanity before a loving and impartial God who created all things and all people. In this one, new humanity, Paul tells both the Colossians and the Galatians, "there is no Greek or Jew, male or female, circumcised or uncircumcised, barbarian, Scythian, slave or free, but Christ is all, and is in all" (Colossians 3:11; Galatians 3:28).

Paula Fredriksen thus argues that Paul, who described himself as both a "Hebrew of Hebrews" (Philippians 3:11) and "apostle to the Gentiles" (Romans 11:13), never "intended to replace Judaism outright with brand-new Christianity." From first to last, she says, Paul remained thoroughly Jewish. He hoped to convert Gentiles into "honorary" Jews, not to convert Jews into Christians. The tragic irony of this, and the main point of Fredriksen's book, is that "the parting of the ways between Christianity and Judaism was by no means inevitable."1

For further reflection:

* See Jacob Neusner, A Rabbi Talks with Jesus (revised edition 2000), Judaism in the Beginning of Christianity (1997), and Judaism When Christianity Began: A Survey of Belief and Practice (2002).

* Read Acts 10–11 about Peter's conversion to acceptance of Gentiles, and Acts 15 about the consternation of the Jewish followers of Jesus upon hearing that Gentiles were converting.

[1] On Fredriksen's book see Peter Brown, "A Surprise from Saint Augustine,"" NYRB (June 11, 2009), pp. 41–42.

Weekly Prayer

Prayer of Mother Teresa and Brother Roger

Oh God, the father of all,

you ask every one of us to spread

Love where the poor are humiliated,

Joy where the Church is brought low,

And reconciliation where people are divided. . .

Father against son, mother against daughter,

Husband against wife,

Believers against those who cannot believe,

Christians against their unloved fellow Christians.A prayer jointly written by Mother Teresa and Brother Roger of Taize. From Kathryn Spink, Mother Teresa: A Complete Authorized Biography (New York: HarperCollins, 1997), pp. 152-153.

Dan Clendenin: dan@journeywithjesus.net

Image credits: (1) Time, Inc.; (2) Galerie Art, Czech Republic; and (3) Jeremy D. Popkin, University of Kentucky.