From Our Archives

For earlier essays on this week's RCL texts, see Dan Clendenin, Honoring Black History Month (2023); Debie Thomas, Salty (2020); Ruth Everhart, Would Jesus Have Marched? (2017); Dan Clendenin, Isaiah and Jesus: Critical Dissent as a Form of Faith (2014).

This Week's Essay

By Amy Frykholm, who writes the lectionary essay every week for JWJ.

Isaiah 58:1: “Shout out! Do not hold back!”

For Sunday February 8, 2026

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Psalm 112

1 Corinthians 2:1–16

Matthew 5:13–20

“Every person always has handy a dozen glib little reasons why he is right not to sacrifice himself.” These words appear in the opening chapter of The Gulag Archipelago, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s voluminous account of Stalin’s terrors. I don’t know about you, wherever you live, but I have lately found these words to be salient. There are at least a dozen reasons why now is not the right moment to raise my voice, why now is not the right time to defend my neighbor. Solzhenitsyn points to something instinctive in many of us — the propensity to avoid conflict, to keep our heads low, to retreat behind walls available for our own self-preservation.

In my small town with a large immigrant community, we’ve been living for months on rumors and sightings. We’ve had big (and contentious) community meetings about the role of immigration in our country and community. We’ve had time to wrestle with our personal fears, to wonder about our roles in unfolding events. Some have gathered and organized and practiced with like-minded people, ready to act when the moment arrives. I personally have spent hours at the front door of a local food pantry, picturing myself springing into action at the sight of an SUV or a man in a mask. I’ve run through a thousand scenarios a thousand times in my head. But in some ways, what appears on the news pages has still been relatively unreal to me. There has still been a place for abstract argument, for debate about heightened rhetoric, and reason not to sacrifice myself. Then Minnesota.

I have close ties to Minnesota and the Twin Cities. I grew up just across the border in South Dakota and went to college an hour south of Minneapolis. My sister works as a professor in St. Paul. Dozens of childhood and college friends live in the surrounding area. My husband was born in St. Paul, where his father pastored a Baptist church. Over the last few weeks, the calls and texts from Minnesota have been pouring in. “Pray for us,” one friend wrote.

My friends and relatives (and their friends and relatives) took to the streets in the bitter cold. They delivered food, filmed and documented arrests, organized school patrols, and raised money for neighbors who were sheltering in place. Ingebretsen’s, a traditional Norwegian grocery store from which my friend Mara orders a yearly lutefisk, held a mutual aid drive. There didn’t seem to be any hesitation in these actions. The moment for hesitation seemed to have long come and gone. The glib little reasons for inaction had disappeared.

|

|

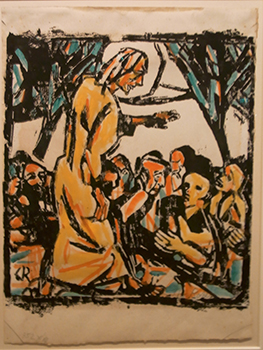

Christian Rohlfs, Bergpredigt (1916).

|

My sister’s Somali-born student — a US citizen — called from the detention center. “I am sorry, professor,” he said with a politeness that seemed out of place in the midst of his terror. “I won’t be in class today. I was picked up driving to campus.” She called the vice provost, checked in with the student’s family, and the school spent the day trying to orchestrate his release. My friend Ellen strategized how to protect her elementary school students. Danielle recorded the arrest of her neighbor. Kyle delivered groceries. “Make no mistake, things are horrible here,” my friend Jason said last week. “But the networks of community relationships that are emerging and deepening and expanding are beautiful and breathtaking. For me they are a real source of hope for what might be when this occupation ends.”

When I opened this week’s lectionary texts, I had just said to my husband, “Maybe I need to write about Minnesota.” Then I saw the first lines of Isaiah 58: “Shout out! Do not hold back!” I had to laugh. The admonitions went on. “Is this not the fast that I choose: to loose the bonds of injustice, to undo the straps of the yoke, to let the oppressed go free, and to break every yoke? Is it not to share your bread with the hungry and bring the homeless poor into your house; when you see the naked to cover them and not to hide yourself from your own kin?” (Isaiah 58:6-7).

While there are many other places where the scriptures counsel silence and even the secret doing of good deeds, this isn’t one of them. Here the idea is to make the light as visible as possible, to shine in the darkness. The text is clear about what exactly light is, how exactly we should go about shining in the darkness. “They will rise in the darkness as a light,” Psalm 112 says. “Their hearts are steady; they will not be afraid.”

|

|

Ad Meskens, Fresco van de Bergrede in de Basilica y Real Santuario de Nuestra Señora de la Calendaria (2023).

|

And so, Minneapolis has become a city on a hill. My friends and their neighbors are no longer asking themselves in any abstract sense what it means to be salt and to be light, what it means to let their lights shine (Matthew 5:13–14). There is no time for that.

In his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, Solzhenitsyn stated, “Everything that is far away and does not threaten, today, to surge up to our doorstep, we accept — with all its groans, stifled shouts, destroyed lives, and even its millions of victims — as being on the whole quite bearable and of tolerable dimensions.” When it washes up on our shore, however, what is bearable and tolerable suddenly shifts.

The scriptures are far away in time and space; the “groans” and “stifled shouts” of the circumstances that gave rise to these powerful passages are barely audible through the ages. And even in our own time and place, we have difficulty knowing how to respond to the “millions of victims” in the context of our own small lives. This is not so much a confession of sin as it is an admission of our fundamental humanness, our limitations, and our frailties.

|

|

Maurice Denis, Baptistry Interior of Saint Nicasius Church of Reims (1934).

|

So many people I know, including myself, have expressed hopelessness and helplessness during this past year, a sense of paralysis, a loss of knowing how to act in a world that seems unrecognizable. We are debilitated by the pace of change. But these passages, collectively, let us know that our sense of helplessness is a mirage. We carry with us, as the whole of our tradition teaches us, a responsibility to our neighbors, to strangers, and to our enemies that lies just outside our door. I can’t answer for you what it means to be a “repairer of the breach, a restorer of streets on which to live” (Isaiah 58:12). Here where I live, however, I know I am relying on the example of others, including the people of Minnesota.

Think of it: thousands upon thousands of these ordinary people, from all backgrounds, not thinking about right and wrong, not posting on social media, not trolling people who disagree with them, but going about the business of shining their own individual lights on their own streets and in their own neighborhoods. This is the righteousness that “exceeds that of the scribes and the Pharisees” (Matthew 5:20). Maybe we need to add an important piece to Solzhenitsyn’s astute observation: maybe when anguish rolls up onto our doorsteps where we can truly see it, righteousness also reveals itself in a new light.

Weekly Prayer

Saint Francis of Assisi (1182-1226)

The Peace Prayer of Saint Francis

Lord, make me an instrument of your peace.

Where there is hatred, let me sow love;

Where there is error, truth;

Where there is injury, pardon;

Where there is doubt, faith;

Where there is despair, hope;

Where there is darkness, light;

And where there is sadness, joy.

O Divine Master, grant that I may not so much seek

To be consoled as to console;

To be understood as to understand;

To be loved as to love.

For it is in giving that we receive;

It is in pardoning that we are pardoned;

It is in self-forgetting that we find;

And it is in dying to ourselves that we are born to eternal life.

Amen.This prayer is attributed to Saint Francis of Assisi, but the author is unknown. One account says the prayer was found in 1915 in Normandy, written on the back of a card of Saint Francis. But it certainly emulates his longing to be an instrument of peace, reconciliation, and redemption in our fallen world.

Amy Frykholm: amy@journeywithjesus.net

Image credits: (1) Wikimedia.org; (2) Wikimedia.org; and (3) Wikimedia.org.