From Our Archives

For earlier essays on this week's RCL texts, see Michael Fitzpatrick, The Great Congregation (2023); Debie Thomas, "What Are You Looking For?" (2020); Dan Clendenin, Three Days with Jesus (2017), Coming Back for More: Why Go to Church? (2014), and The Outrage of Outsiders: Why So Many People Dislike Christians (2008).

This Week's Essay

By Amy Frykholm, who writes the lectionary essay every week for JWJ.

John 1:33: “I myself did not know him.”

For Sunday January 18, 2026

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Psalm 40:1–12

1 Corinthians 1:1–9

John 1:29–42

A few years ago I signed up for a painting workshop called “Exploring Divine Love through Paint” taught by Angela Hummel, who was at the time a PhD candidate at the Iliff School of Theology in Denver. I am no visual artist, but I was attracted to the idea of experimenting with color in my endless quest to glimpse the nature of God. Paint is an unfamiliar language for me, so I thought — as often happens when you work with a foreign language — I might see something I don’t usually see.

Hummel began the day with a poem attributed to Rabi’a Basri, an eighth-century Sufi poet whom I had never heard of, even though she is considered one of three preeminent Qalandars (most holy people) of the Sufi tradition. This version of the poem comes from Daniel Ladinsky’s Love Poems from God, a compilation of mystical poetry from both Christian and Muslim traditions.

Would you come if someone called you by the wrong name?

I wept, because for years He did not enter my arms;

then one night I was told a

secret:

Perhaps the name you call God is

not really His, maybe it

is just an

alias.

I thought about this, and came up with a pet name

for my Beloved I never mention

to others.

All I can say is—

it works.

|

|

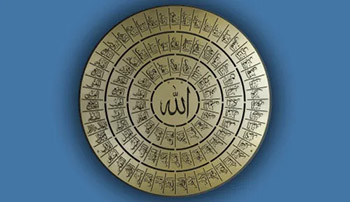

99 Names of God in the Islamic Tradition.

|

I was struck by two things in this poem. One was the idea that the name I call God might not actually be God’s name. I can think of many ways that I call God by the wrong name — names derived from history, culture, tradition, personal failings, even theology. If I am working with the wrong name or the wrong names, then is it a wonder that I so often feel a distance between me and God?

But the other thing that struck me is Rabi’a’s solution. She doesn’t try to identify the right name derived from yet another external source. Instead, she dives into her own inner experience to find what Ladinsky renders as a “pet name,” an affectionate, intimate name that is capable of expressing her devotion.

Even then she doesn’t claim that she’s found the right name for God. By deriving her own name for the Beloved and keeping that name to herself, she’s found something “that works.”

This week’s lectionary readings wrestle with both divine names and divine naming. In the first lines of Isaiah 49, the prophet says, “The Lord called me before I was born” (Isaiah 49:1). It bears remembering that the word “Lord” in Hebrew is often substituted with HaShem, which can be translated as “the Name.”

|

|

The Tetragrammaton (YHWH), the Main Hebrew Name of God Inscribed on the Page of a Sephardic Manuscript of the Hebrew Bible, 1385.

|

This substitution is made for two reasons. One is because the Hebrew name “Lord” is considered too holy to be uttered. The other is because humans forget that the names we use for God are all substitutes, poor approximations, maybe even, as Rabi’a says, “wrong.” Hebrew keeps this reminder in front of us at all times, and when HaShem is substituted, it makes us even more mindful of the names we are choosing. This wisdom is echoed in other spiritual traditions as well. I keep thinking of the opening lines of the Tao Te Ching: “The Name that can be named is not the eternal name.”

Like all people, before I had a human name, I was in communication with the divine Name. This mysterious Name, the passage says, gave me a name. When I think about this, I sincerely doubt this name was Amy — although that’s the one I went out into the world with. I learned to answer to it, but I often feel like I could apply Rabi’a’s words to my own name. Would you come if you were called by the wrong name? I keep calling myself by the wrong name and so I keep not arriving. I feel the prophet’s confession, “I have labored in vain; I have spent my strength for nothing and vanity” (Isaiah 49:4). Somehow, I feel that I’ve been working with the wrong names.

This week’s Gospel is full of names. John the Baptist names Jesus “Lamb of God.” This naming leads to other naming. Rabbi, Teacher, Messiah, Anointed One, Chosen One — they follow in a string, moving from Aramaic to Hebrew to Greek to English. The passage ends with Jesus naming Simon with the Aramaic word Cephas, which the text tells us becomes Peter in Greek.

|

|

Lamb of God Mosaic in Presbytery of Basilica San Vitale, A.D. 547, Ravenna, Italy.

|

Did Simon feel a shock of recognition when Jesus said, “You are to be called Cephas,” the Aramaic word for rock (John 1:42)? Or did he wonder: how could that possibly be my name? Was Cephas a version of the name he had been called in his mother’s womb or was it something he had yet to live into, something he had yet to become?

Peter’s journey perhaps demonstrates that learning to call our spiritual realities by their right names is not so much the arrival at a destination as it is a path that we follow. In The Message of Micah, Howard Thurman writes that to walk humbly with God, he must “come to grips with who I am, what I am as accurately as possible: a clear-eyed appraisal of myself.” This feels a little like trying to find the right name, even if it isn’t a name that ever forms itself in syllables.

Thurman continues, “And in light of the dignity of my own sense of being, I walk with God step by step as God walks with me. This is I, with my weakness and my strength; this is I, a human being myself. And it is that that God salutes. So that the more I walk with God and God walks with me, the more I come into a full-orbed significance of who I am and what I am.”

This strikes me as the purpose of naming and being named: it involves a gradually more “full-orbed” understanding of who we are and what we are. “This is I,” a mystery, a complexity, a named, misnamed and yet renamed creature, a human being myself, in search of the Name.

Weekly Prayer

C.S. Lewis

He whom I bow to only knows to whom I bow

When I attempt the ineffable Name, murmuring Thou,

And dream of Pheidian fancies and embrace in heart

Symbols (I know) which cannot be the thing Thou art.

Thus always, taken at their word, all prayers blaspheme

Worshiping with frail images a folk-lore dream,

And all men in their praying, self-deceived, address

The coinage of their own unquiet thoughts, unless

Thou in magnetic mercy to Thyself divert

Our arrows, aimed unskillfully, beyond desert;

And all men are idolaters, crying unheard

To a deaf idol, if Thou take them at their word.

Take not, O Lord, our literal sense. Lord, in thy great

Unbroken speech our limping metaphor translate.C.S. Lewis (1898–1963) was a Professor of Medieval and Renaissance Literature at Oxford and Cambridge universities. In 2013, on the 50th anniversary of his death, he was honored with a memorial stone in the Poets’ Corner of Westminster Abbey, alongside Chaucer, Shakespeare, Milton, Handel, Dickens, and many others.

Amy Frykholm: amy@journeywithjesus.net

Image credits: (1) Abrahamic Study Hall; (2) Wikipedia.org; and (3) Wikipedia.org.