From Our Archives

For earlier essays on this week's RCL texts, see Dan Clendenin, When Hope and History Rhyme (2022); Debie Thomas, On Confession (2019); Dan Clendenin, The Pharisee and the Tax Collector (2016), Comfort and Critique: The Prophet Joel and a Plague of Locusts (2013), Lord Have Mercy: What’s Wrong About Being Right (2010), and Seven Little Words: The Only Prayer You’ll Ever Need (2007).

This Week's Essay

By Amy Frykholm, who writes the lectionary essay every week for JWJ.

Psalm 84:1-7: “How lovely is your dwelling place, O Lord of hosts.”

For Sunday October 26, 2025

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Psalm 65 or Psalm 84:1–7

2 Timothy 4:6–8, 16–18

Luke 18:9–14

We were hungry. We’d been to morning mass at Canterbury Cathedral. We’d heard a thought-provoking sermon, delighted in the cathedral choir, taken in the majestic heights and the almost silent crypt, and tried to ponder the depth of the history of Christianity in England. Now it was time to eat.

Before lunch, however, we thought we’d quickly dash up the road and visit the other two sites significant to the story of how Christianity was re-introduced to England in the sixth century. The first site was St. Augustine’s monastery. The second startled me in a way that interrupted my thoughts of lunch.

St. Martin’s is the oldest church in England still being used as a church. “In England?” our enthusiastic docent, Jeanne, said, “How about the oldest functioning church in the English-speaking world!” St. Martin’s is nestled in a small, green hiding spot, a half mile from the glorious Cathedral. I got the feeling that even on this summer day at the height of tourist season in Canterbury, even though this was a UNESCO World Heritage site, few people walked the extra paces to see it. While we were there, we saw only one other visitor. We walked through tumbled-down tombstones, worn smooth and nameless by time, and up the steps into the small rectangular building.

|

|

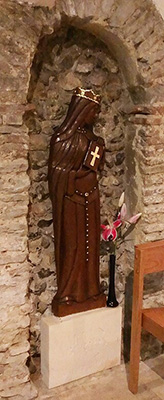

St. Bertha of Kent, Wooden Statue, South Wall of St. Martin’s Church, Canterbury.

|

No one knows when this building was built. It was “in Roman times,” Jeanne noted, adding that there is research underway to determine if this was perhaps the site of a Roman temple or a church abandoned after the fall of the Roman Empire. In the sixth century, when pagan Prince Aethelburt, whom the Frankish Princess Bertha was about to marry, offered it to his bride as part of their elaborate marriage agreement, it was a tiny ruin of a building. The Venerable Bede — widely regarded as the greatest of the Anglo-Saxon scholars — wrote that the church was dedicated to St. Martin of Tours, although in my mind it will always be St. Bertha’s. A teenaged bride from a dysfunctional family, she agreed with Aethelburt that she could bring her own confessor here, practice her own religion, and set up in this place that no one was using anyway. I’m sure it seemed a harmless enough arrangement.

Today, the little building is replete with bricked-over doors and windows, as different eras offered up their own ideas about coming and going. Jeanne walked us outside the building to show us what archeologists believe was the earliest entrance, a little door frame of stone invisible from the inside. There was a place where St. Bertha could have washed before worship and then entered.

The littleness of this door allowed me to perceive it as it might have been in 594 — a structure lost to time, lost in the woods, a “who cares” sort of place, where Queen Bertha would find her way alone. Through that door, I saw the intimacy of her faith, and felt the solitude that she would have carried. Even though a queen, she was at the margins of two cultures, situated between pagan and Christian.

“I want to be sure that Queen Bertha gets her due,” Jeanne said. “Over there,” she gestured in the direction of the Cathedral, “it’s all Augustine this and Augustine that. But it was a woman who brought Christianity back here.”

|

|

Ancient Entrance to the Chapel, St. Martin’s Church, Canterbury.

|

That may not be entirely true, as Jeanne herself admitted. There may have been Christians in England since the Roman times, and they had never left. They just didn’t possess cultural dominance — and that’s an important theme in this story. When we speak of bringing Christianity “back” to England, we aren’t talking about the faith itself — that business of the heart. We are talking about power, about relationship to empire. We are telling the story of how Christianity gained cultural dominance. Human hearts are involved in that story, but they aren’t quite as central as they might have been when Bertha entered through that tiny side door.

Bertha and her chaplain, Luidhard, eventually sent for Augustine, a monk charged with establishing more public structures for the church. When Augustine arrived in 597, he initially used St. Martin’s as his headquarters, had it enlarged, and baptized the converted king, Aethelburt. Later a tower was added — in my opinion a vain attempt to improve on what Bertha had initiated.

Jeanne was eager to share stories that were embedded in the very architecture of the building. When the Victorians installed a new roof in the late 19th century, they stumbled on a chrismarium (a vessel used to hold holy oils) that a vicar had hidden in the walls in the 16th century, when Henry VIII was plundering churches to melt down metals for his war efforts. When found, the chrismarium was claimed by the Cathedral and put on display there, but the docents of St. Martin’s lobbied to bring it back and put it on display in the tiny building.

Despite Christendom’s cultural dominance in so many places over the past 1000 years, I’ve often wondered if Christianity isn’t, at its best, a religion like Bertha’s — built of solitude, lived on the margins. In the midst of the talk about church decline, I’ve found myself wondering about religious atmospheres and places that might most deeply speak to my own heart.

|

|

St. Martin’s Church, Canterbury.

|

In my mind’s eye, I am drawn back to St. Bertha's again and again, to the quiet green, the ancient walls, the comings and goings. I find myself entering in my imagination through that side door, and wondering what my soul might do with exile and alienation and being wed to things that I don’t fully understand or desire. What Bertha brought to the island was not a public religion. What she brought was a personal faith, an intimate desire, an inner life that she requested space for.

For me, St. Bertha’s is the kind of place where “even the sparrow finds a home and the swallow a nest” (Psalm 84:3), where there is space for my innermost longings, where my heart finds an “early rain” (84:6). You can feel the ancient, earthy prayers rising up from the ground. When you come to St. Bertha’s, you don’t do so to feel the grandeur. You come to reconnect — to history, to the earth, to the Spirit that attends to the littleness of our lives as well as the arc of history. In the midst of all the talk about dominance and empire, it is a sanctuary where the soul might find an inner spring.

Weekly Prayer

Psalm 84

How lovely is your house!

My soul thirsts for, longs for your courts.

My heart and my flesh leap for joy

In your presence, life’s sovereignty

Just as the sparrow has found her proper nest

And the swallow a corner for herself

Where she may nurture and fledge her young

So I have found your altars

You who trail clouds of glory

To whom I look for my soul’s satisfaction

Happy are the ones whose hearts confide in you

Whose feet walk the pilgrim pathways

Passing the valley of weeping

They change it into a spring

And the morning rains cover it with blessing

The go from strength to strength, tower to tower

Appearing before you at Zion’s Mount

O you who trail clouds of glory—

Listen to me, incline your ear

And look upon my glistening face

For better is a day in your courts

Than a thousand days anywhere else

I would rather wait at the threshold of your house

Than dwell comfortable in the tents of the strong

For you are a warm sun, a glinting shield

Who beams grace, who shines glory

Never withholding goodness

From those who walk with integrity—

O you whose glory blazes behind you!

Happy is the one whose trust rests solid with youTranslated by Norman Fischer from Opening to You: Zen Inspired Translations of the Psalms (Viking, 2002), p.105.

Amy Frykholm: amy@journeywithjesus.net

Image credits: (1) Wikipedia.org; (2) Wikipedia.org; and (3) Wikipedia.org.