From Our Archives

For earlier essays on this week's RCL texts, see Dan Clendenin, Lovers of Money (2022); Debie Thomas, Notes to the Children of Light (2019); Dan Clendenin, Shared Civic Values (2016), “Horror Grips Me:” Remembering Congo (2013), Faith and Wealth: Gospel Lessons, Wall Street Examples (2010), How Long, O Lord: Why the Delay in Divine Intervention (2007), and Portfolio Performance (2004).

This Week's Essay

By Amy Frykholm, who writes the lectionary essay every week for JWJ.

Luke 16:12: “And if you have not been faithful with what belongs to another, who will give you what is your own?”

For Sunday September 21, 2025

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Psalm 79:1–9 or Amos 8:4–7

Psalm 113

1 Timothy 2:1–7

Luke 16:1–13

Gerald was the produce manager at the local Food Town grocery store. One of his jobs was to separate out fruits and vegetables that were going bad. Every day he generated a cardboard box of slightly (or sometimes greatly) rotting fruits and vegetables, and for many years he carried this box to the dumpster.

But one day he got into a conversation with our priest, Ali, who oversaw the Community Meal. Between the two of them, they crafted a plan. What if, instead of carrying that box to the dumpster, he gave it to her instead? Then she could sift through the produce a second time and use whatever she could to make the Community Meal. From a cook’s point of view, this was a huge boon. Suddenly I (one of the cooks) had fresh fruits and vegetables to work with, and the quality of what I served went up dramatically.

Over 25 years, this small flash of inspiration became a thriving food rescue program with over 100,000 pounds of food brought to our little church every year from three regional grocers. We now have sophisticated pick-up and distribution routines and dozens of volunteers who help get “expired” but still good food into the hands of those who can put it to use.

But when Gerald and Ali first started talking, none of this existed. Some time later, Food Town closed, and Gerald went to work at the other national chain grocery store in town. He continued to sort fruits and vegetables, and Ali continued to pick them up. But now the volume was much higher. She would fill her car, and we would line the church hallway with boxes of produce to create a little “free grocery store.” Connections were made; the community was growing. One man said to me, “I haven’t eaten a cucumber since my grandmother was alive.” For the first time, our community’s Spanish-speaking neighbors came during meal times to “shop.”

|

|

Marinus van Reymerswaele, The Parable of the Unjust Steward (1540).

|

Back at the grocery store, however, controversy was brewing. Employees in other departments began wondering why they were carting perfectly good food to the dumpster when there was already someone willing to pick it up. The deli became involved, then the bakery and soon the meat department. There were also subtle, but growing, shifts in loyalty. Some employees wondered just how “bad” food needed to be before they could put it in the magic cart. Others began expressing disgruntlement, questioning why some people deserved free food at all. Soon enough, management entered the fray. Word came down from on high: no more food to St. George. In the parade of managers through the store (more than a dozen in ten years), there was a wide and impassioned spectrum of opinion. One manager told Ali, “I wouldn’t give you that food if you were pigs at the zoo.”

Some employees lost their jobs in the initial dust-up, including Gerald. Articles and letters were published in the local paper. The national corporation became directly involved. It was a mess. Gradually, once much water had passed under the bridge, compromises were reached. Meanwhile, a national conversation about food waste was growing. Grocery stores began to see it to their advantage to donate food that would otherwise be thrown away. New managers were trained in new practices. The story basically had a happy ending.

Not for Gerald, though. After he lost his job at the grocery store, he also lost his house and his marriage. He secretly lived in the local cemetery for seven years, camped out among the pines. Today he does have housing and a renewed and deep friendship with his ex-wife. He continues to eat at the Community Meal, where he is remembered and treasured for his role in starting the food rescue operation. There are many angles from which to look at this story, from which to distribute blame and credit, if that’s what we are intended to do.

|

|

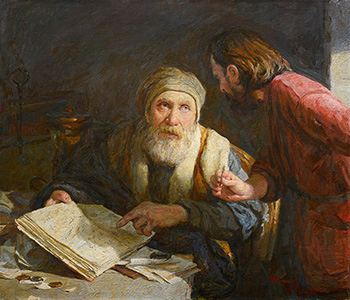

Andrei Mironov, Parable of the Unjust Steward (2021).

|

I thought of Gerald and Ali when I read the story of the so-called dishonest manager in Luke 16. The man has a job that, according to the story, he doesn’t perform particularly well. I imagine lots of small infractions over the years — a little skimmed off the top here, a bad deal there, missed or forgotten details elsewhere. Word finally reaches the owner that this manager is incompetent, if not outright unscrupulous. When the manager realizes he is about to lose his job, he comes up with a plan. In his post-work life, he’s going to need friends, people whose couches he can sleep on, people who owe him a little something and will be willing to return a favor.

This isn’t a great plan. We can all imagine how long it will last and how it will end. But it’s the best idea he’s got. So he goes about changing the bills that the owner’s debtors have. If they owe 100 jugs of olive oil, he makes it 50. If they owe 100 containers of wheat, he cuts it to 80. Instant friends! In perhaps the most mysterious line of the parable (16:8), the owner “commends” the dishonest manager for this action, and we are left scratching our heads. Commends him for what exactly? Clever deviousness? Ingenious scheming?

The head-scratching is precisely the point. Jesus deprives us of the positions we so naturally take. When we hear parables, we are accustomed to identifying good guys and bad guys. The good Samaritan, the good father of the prodigal son. The bad Pharisee, the bad farmer building bigger barns. But in this case, with whom do we identify? The owner, about whose practices and business we know nothing? The manager, whose motives and relationships aren’t entirely clear? The debtors, who are glad to have a little skimmed off in their favor? Our habitual black and white thinking is of no use here.

Jesus continues to play with that problem in his ensuing commentary. “The children of this age are more shrewd in dealing with their own generation than are the children of light” (16:8). “Make friends for yourselves by means of dishonest wealth so that when it is gone they may welcome you into the eternal homes” (16:9). It certainly feels like there is a bit of slyness on Jesus’ part. He knows our tendency to collapse quickly into oppositional thinking, so he’s going to make this hard for us. I think of the poet Rumi’s lines, “Out beyond ideas of right-doing and wrong-doing, there is a field. I’ll meet you there.”

|

|

The Unjust Steward. Illustration from The Child's Own Book of Scripture: Pictures of the New Testament (c. 1870).

|

So out beyond right-doing and wrong-doing, what do we find? At least one thing we find is grace. In fact, it astonishes me that when the manager creates a plan to save himself, he uses grace. When the owner responds to the manager, what does he do? He demonstrates grace. There is even grace shown to us in our desire to keep reading the parable through a judgmental lens. Keep trying that, Jesus seems to say with a laugh. See where it takes you.

The more I read the parable, the more I see my own inner manager — trying to manage the unmanageable (life itself), using any means necessary. In one of his many thought-provoking sayings, Meister Eckhart writes, “The inner work one has to do is the practical realization of grace.” My inner manager always has a new scheme, a new attempt to get her needs met and to manage the affairs of others to her advantage. If I stop assigning the categories of blame and adopt the tool of grace, what might I learn about my own inner work?

Like many of Jesus’ parables, this might be a story about “the practical realization of grace” in both the inner life and the outer life, about the grace we need both inside and outside ourselves. It’s not a set of rules to live by. We aren’t going to receive an easy moralistic take-away. But we might find a willingness to open ourselves to the ever-ongoing work of grace in our lives.

Weekly Prayer

Howard Thurman (1899-1981)

I must let go.

For so long I have held to the habit of holding on. Even my muscles

Are tense; deeply fearful are they

Of relaxing lest they fall away from their place.

I cling clutchingly to my friends

Lest I lose them.

I live under the shadow of being supplanted by another.

I cling to my money, not so much by a wise economy and a thoughtful spending

But by a sense of possession that makes me depend on it for strength.

I must let go—deep at the core of me

I must have a sense of freedom— A sure awareness of detachment— of relaxation.I must let go of everything.

I must let go of pride. But—

What am I saying? Is there not a sense of pride

That supports and sustains all achievement,

Even the essential dignity of my own personality?

It may be that I must let go my dependence upon triumphing over my fellows, which

seems

To give me a sense of security in their midst.

I cringe from my pain; I do not relish

The struggle of life but I do not want to let go

Because the hurt and the tension of contest feed

The springs of my pride. They make me deeply aware.But I must let go of everything.

I must let go of everything but God.

But God—May it not be

That God is in all the things to which I cling?

That may be the hidden reason for my clinging.

It is all very puzzling indeed. When I say

I must “let go of everything but God”

What is my meaning?I must relax my hold on everything that dulls my sense of

God,

That comes between me and the inner awareness of God’s Presence

Pervading my life and glorifying

All the common ways with wonderful wonder.

“Teach me, O God, how to free myself of dearest possessions,

So that in my trust I shall find restored to me

all I need to walk in Thy path and to fulfill Thy will.

Let me know Thee for myself that I may not be satisfied

With aught that is less.”Howard Thurman (1899-1981) was an American philosopher, theologian, mystic, and Civil Rights leader who was a key mentor to Martin Luther King Jr. and whose work only grows in significance in contemporary contemplative movements. Among his many books are Jesus and the Disinherited (1951) and The Inward Journey: Meditations on the Spiritual Quest (1961). This poem is from Meditations of the Heart (Harper, 1953).

Amy Frykholm: amy@journeywithjesus.net

Image credits: (1) Psephizo: scholarship, serving, ministry; (2) Wikimedia.org; and (3) Look and Learn: History Picture Archive.