From Our Archives

For earlier essays on this week's RCL texts, see Dan Clendenin, Be On Your Guard (2022); Debie Thomas, Rich Toward God (2019); and Dan Clendenin, Christ is in All (2010).

This Week's Essay

By Amy Frykholm, who writes the lectionary essay every week for JWJ.

Ecclesiastes 1:14: “All is vanity, a chasing after the wind.”

For Sunday August 3, 2025

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Psalm 107:1–9, 43 or 49:1–12

Colossians 3:1–11

Luke 12:13–21

Rick felt confident the night before the race. He was staying at our house with his friend and trainer, Danny. The race was 100 miles. Runners would start at 4 a.m. at 10,200 feet of elevation and then ascend to 12,600 feet over a mountain pass called, ironically or inspiringly depending on your perspective, Hope. The 50-mile mark was at 10,300 feet, where racers would turn around for the climb back to 12,600 feet and the final 40 miles to the finish line. Only about half the runners finish the race in a given year, but Rick wasn’t worried about that. He did have some particular questions about the course (“Do most people change into dry socks after the river crossing?”), but finishing was an absolute given.

What he and Danny mostly discussed was: would Rick be in the top 10 or the top 20? Did he have a chance to come in like a dark horse and win the whole thing? They’d studied Rick’s splits for other races, and his times were far ahead of what was typical for this race. As we listened in, my husband and I stole glances at each other — worried they were not taking into adequate consideration the extreme altitude and rough terrain.

Race day started inauspiciously at 3 a.m., when Rick whacked his head in the dark on the low beam of our staircase. But once the race was underway, he was indeed fast. We followed him on the race app on our phones. Just as he’d predicted, he was in the top 10 and then dropped slightly back into the top 20. But after the second aid station, we couldn’t see Rick making any progress. His bib number on the app just stalled. We started to worry: had he gotten injured? Was there a technical problem with the app? Hours went by. We finally texted Danny, “What’s up with Rick? Is he OK?”

|

|

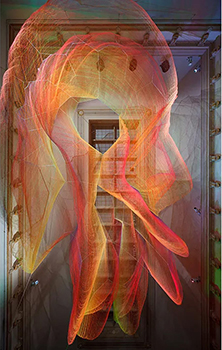

Janet Echelman, 1.8 (2015). Photograph by Ron Blunt/ Renwick Gallery/ SAAM.

|

Rick was struggling. He was struggling with the altitude, with the terrain, with keeping food down, with his body temperature. Just struggling. There was no more talk of top 10 or top 20. At 50 miles, Rick had given it all he had, and Danny made the long drive through the dark valley to pick him up on the far side of Mount Hope. Rick joined hundreds of other racers with the dreaded designation DNF—Did Not Finish.

To be honest, few things say to me “All is vanity, a chasing after the wind” (Ecc. 1:14) more than ultra running. I’ve been watching this race for years now. I’ve volunteered at aid stations; I’ve greeted racers at the finish line; I’ve cheered them on a lonely forest path in the middle of the night. And the more I watch this race, the more it baffles me. My friend Robin and her failing kidneys. My friend Jack’s 14 foot surgeries. My friend Brad vomiting through the night from mile 50 to mile 80, unable to hold down even a sip of water as his body rebelled. My husband once worked the aid station where most runners come through between three and five in the morning. “Grim,” he said. “Just grim.”

|

|

For 1.8, Janet Echelman used fibers developed originally for NASA spacesuits. Photograph by Ron Blunt/ Renwick Gallery/ SAAM.

|

One year I volunteered at the finish line from 2 a.m. to 5 a.m., and my sense of mystery about the whole enterprise deepened. I saw with my own eyes that the better a person performs in this particular race, the less glory is involved. People can have the best race of their lives and cross the finish line at 2:30 a.m. to the sound of perhaps two hands clapping. They run up the empty boulevard in the dark and silence. When they cross, a spouse or friend might be there to offer a hug. Then they limp off to a medical tent to have their vital organs tested. That’s it for rewards. Oh, and an oversized belt buckle.

So what accounts for this? “Vanity of vanities, says the Teacher, vanity of vanities! All is vanity” (Ecc. 1:2). Every year the race founder delivers a version of the same cheerleading speech that serves almost like scripture for this community of racers. “You are stronger than you think you are,” he says. “You can do more than you think you can.” Sure. But the question he never answers is, “So what?”

I only begin to make sense of this race when I look at its failures and its losses. If ever there was a race that is not run to be won, this is it. “Some wandered in the desert wastes,” reads Psalm 107, “finding no way to an inhabited town; hungry and thirsty, their soul fainted within them.” From the trail, racers might see the distant lights of the town. Perhaps mentally they know that each step brings them closer to those lights. Maybe they even believe the founder that they can do more than they think they can, though their souls do in fact grow faint within them. “They will run and not grow weary?” (Isa. 40:31). Fat chance. You will grow weary. You will be battered down. You will be faint. The race is, among other things, a metaphor for what happens when you come to the end of your resources, to the end of your self, when you confront the great naked, middle-of-the-night silence that seems to want to own you and take you into itself. There’s a soul inquiry in those moments that goes far beyond any race-day hype.

|

|

At the exhibit at the Renwick Gallery in 2015, artificial wind gusts moved the net. According to Echelman, "The piece aims to show how interconnected our world is, when one element moves, every other element is affected.” Photograph by Ron Blunt/ Renwick Gallery/ SAAM.

|

Maybe in the agony and even foolishness of ultra racing, racers’ own hidden life is sought. Not their accomplishments, not their bragging rights, nothing that can be measured by the standards of the society. A small death, as the Buddhists call it, to instruct them on the path to death itself. And then maybe there are hidden riches, because certainly all of the earthly and material riches have been poured out. “Emptiness makes water run uphill,” writes Meister Eckhart. There are no words for these kinds of encounters and discoveries. People don’t talk about them when they tell their friends the story of the race. Those insights stay in the darkness by the side of the road.

At the beginning of Julian of Norwich’s account of the sickness that led to her revelations of divine love, she writes, “I wished that the sickness would be so hard as to the death, so that I might in that sickness undertake all the rites of holy church, even myself believing that I would die, and all creatures might suppose the same that saw me.” Drawn as I was to Revelation of Divine Love, I was haunted by this desire of hers. I sought to be well. I wanted resources in my life that would lead to healing and wholeness, not to brokenness. I almost stopped reading Julian at this point, thinking she would lead me off course.

But the more I meditated on this desire, the more I wondered: maybe she was looking for a path out of herself and out of her society and even her religion, out of its habits and structures and certainties. Why did she want to be sick? So that she could “undertake all the rites of holy church.” If she was sick unto death, then the priest would come and give her last rites: the very last thing that the church could do for her. After that was uncharted territory. After that was maybe something that she could not know in her healthy body with her society still dictating every choice she made. Maybe on the far side of last rites was the freedom and intimacy with God that she craved.

Perhaps this lost, empty self, this brokenness, whether found in a running race or found in the ordinary paths of living, is the treasure that lies on the other side of vanity. Your life, your true life, the one you’ve been seeking, is hidden in Christ, in the broken one (Col. 3:3).

Weekly Prayer

Pablo Neruda (1904-1973)

And it was at that age… Poetry arrived

in search of me. I don't know, I don't know where

it came from, from winter or a river.

I don't know how or when,

no, they were not voices, they were not

words, nor silence,

but from a street I was summoned,

from the branches of night,

abruptly from the others,

among violent fires

or returning alone,

there I was without a face

and it touched me.I did not know what to say, my mouth

had no way

with names,

my eyes were blind,

and something started in my soul,

fever or forgotten wings,

and I made my own way,

deciphering

that fire,

and I wrote the first faint line,

faint, without substance, pure

nonsense,

pure wisdom

of someone who knows nothing,

and suddenly I saw

the heavens

unfastened

and open,

planets,

palpitating plantations,

shadow perforated,

riddled

with arrows, fire and flowers,

the winding night, the universe.And I, infinitesimal being,

drunk with the great starry

void,

likeness, image of

mystery,

felt myself a pure part of the abyss,

I wheeled with the stars,

my heart broke loose on the wind.Translated by Alastair Reid.

Pablo Neruda (1904–1973) was a Chilean poet and diplomat who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1971. Neruda was exiled from 1948–1951 when communism was declared illegal in Chile. Later he served as a diplomat and an advisor to President Salvador Allende. When Allende was overthrown in a coup d’état that made way for Augusto Pinochet’s regime, Neruda was already dying of cancer. Colombian novelist Gabriel Garcia Márquez called Neruda “the greatest poet of the 20th century in any language.”

Amy Frykholm: amy@journeywithjesus.net

Image credits: (1–3) Smithsonian Magazine.