For Sunday December 6, 2020

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Isaiah 40:1-11

Psalm 85:1-2, 8-13

2 Peter 3:8-15a

Mark 1:1-8

Where do you go for comfort? If I were to ask you to make a list of the places you associate with healing, restoration, nurture, and consolation, what sorts of places would you list? The woods? The ocean? A mountain retreat? A favorite corner of your home?

In our readings for this second week of Advent, comfort resides in a place we wouldn’t expect. A hard place. A paradoxical place. If you seek the comfort of God, these Scriptures tell us, head to the wilderness.

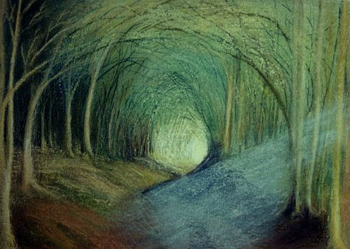

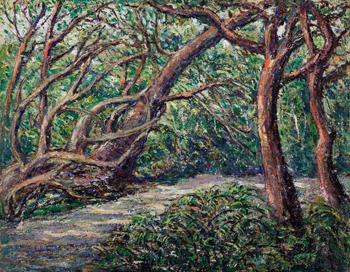

Just to be clear, the "wilderness" these texts describe is not the wilderness of a pristine national park, a well-tended shoreline, or the forest havens we associate with sleeping bags, campfires, and s’mores. The wilderness of the Bible is harsh and austere, bleak and inhospitable. Its weather patterns are unpredictable. Its water sources are scarce. There are no established trails to be found amidst its rocky crevices; if we want a path, we have to forge it by our own sweat, blood, and tears.

The wilderness of Scripture, moreover, isn’t a destination we choose by ourselves. Sometimes, we’re taken there against our will. By illness, or loss, or trauma, or hardship. The wilderness is a place of captivity. Of exile. We end up there when our careful plans fail. When someone we trust betrays us. When our beloved dies. When the faith we’ve practiced so effortlessly, suddenly dries up. The wilderness of the Bible is not by any stretch of the imagination a place we’d wish to inhabit.

|

Yet it is in this kind of hostile desert that God “speaks tenderly” to God’s people. It is when we “prepare the way of the Lord” in the wilderness, when we “make straight in the desert a highway for our God,” that the promise of consolation comes: “Comfort, comfort my people, says your God.”

Our reading from Second Isaiah describes an assembly of the heavenly host. The topic of conversation in the divine council is the situation of God’s children on earth -- the children of Judah who have been exiled from their homeland, their identity, their kin, and their temple. These are people who have been robbed, ravaged, demoralized, and crushed by their Babylonian captors, driven away from all that is safe and familiar. In every way imaginable, they are in the wilderness.

Likewise, in our Gospel reading, Mark describes John the baptizer appearing “in the wilderness,” proclaiming a baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of sins. John’s message, like Isaiah’s, is aimed at a people living under foreign rule (in this case, Roman), and suffering the loss of autonomy, dignity, and freedom that is part and parcel of empire.

As we move deeper into Advent, and consider what it means to wait for the coming of Jesus, these readings challenge us to consider hard questions about location. Why does Scripture ask us to dwell in the wilderness in the weeks leading up to Christmas? Why must God’s comfort come to us in such barren, desolate settings? Why is joy hidden in the desert? Here are some possible reasons:

First, the wilderness is a place that lays us bare. It's a place where we must contend with our own powerlessness. In the wilderness, there’s no safety net. No Plan B. No savings account or National Guard. In the wilderness, life is raw and risky, and our illusions of self-sufficiency fall apart fast. To locate ourselves at the outskirts of our own power is to acknowledge our vulnerability in the starkest terms. In the wilderness, we have no choice but to wait and watch as if our lives depend on God showing up. Because they do. And it’s into such an environment — an environment so far removed from power as to make power laughable — that the word of God comes.

|

Secondly, the wilderness softens us towards repentance -- the repentance that makes God’s consolation and comfort possible. When John the Baptist proclaims his baptism of repentance, he does so in the desert -- away from the temple, away from the city, away from everything his listeners consider routine and familiar. Why? Because something about the harsh, bewildering environment of the desert brings people to their knees. It shows them what is really in their hearts, and it allows their hardened exteriors to melt in penitence, sorrow, and hope.

I know that for us 21st century Christians, “sin” and “repentance” are loaded words. Many of us, particularly those of us who grew up experiencing the Church's teaching on sin as a weapon, hesitate in its presence. We associate "sin" with guilt, self-loathing, and hellfire. We approach it with fear rather than confidence.

But whether we like it or not, Advent begins with an honest, wilderness-style reckoning with sin. As Isaiah describes it, the God who comforts is also the God who judges. The God who forgives is also the God who convicts. This is not because God is cruel, capricious, or withholding, but because God knows how deeply sin distorts and damages our souls. God sees what sin does to people suffering on the margins. God sees what it does to those who wield power. God sees what sin does to Creation itself.

Is it possible that acknowledging our sin might become an occasion for relief? Maybe, if we can get past our baggage and risk the desert, we will find comfort in the fact that we are hopelessly enslaved to something we cannot fix on our own. Maybe, confessing our need for deliverance will lead us to a place of profound comfort. A place where God, who alone has both the power and the will to forgive us, can make us whole.

|

What is sin? Growing up, I was taught that sin is "breaking God's laws." Or "missing the mark," as an archer misses his target. Or "committing immoral acts." These definitions aren't wrong, but they assume that sin is a problem primarily because it angers God. But God's temper is not what's at stake; sin is a problem because it kills us. Sin is estrangement, disconnection, sterility, and disharmony. Sin is a frightened resistance to an engaged life. It is a walking death, and the God who wishes to comfort us cannot do so when we are dead to God, the world, and ourselves. In the wilderness, on our knees, at the very end of ourselves, we learn the meaning of resurrection.

Lastly, the wilderness is a place where we can see the landscape whole, and participate in God’s great work of leveling inequality and oppression. Our reading from Isaiah describes a day when “every valley shall be filled, and every mountain and hill made low, and the crooked shall be made straight, and the rough ways made smooth.”

Unless we’re in the wilderness, it’s hard to see our own privilege, and even harder to imagine giving it up. No one standing on a mountaintop wants the mountain to be flattened. But when we’re wandering in the wilderness, and immense, barren landscapes stretch out before us in every direction, we’re able to see what privileged locations obscure. Suddenly, we feel the rough places beneath our feet. We experience what it’s like to struggle down twisty, crooked paths. We see arrogance in the mountains and desolation in the valleys, and we begin to dream God’s dream of a wholly reimagined landscape. A landscape so smooth and straight, it enables “all flesh” to see the salvation of God.

|

Our reading from Isaiah suggests that this great leveling, this great reversal of high and low, rich and poor, full and empty, arrogant and humble, must happen before the Lord appears to gather his flock in his arms. The “highway” that will bring God into our midst is the highway we must pave through this leveling, this toppling, this sustained insistence on justice, healing, reparation, and liberation. If we don’t consider this Good News, then we need to interrogate where we’re located. Are we the mountains that must be brought down? Or the valleys that will be filled?

Our Advent texts this week assume that we are a people in exile. A people wandering in the wilderness. Is this true? Where are you located during this holy season? How close are you to power, and how open are you to risking the wilderness to hear a word from God? What might repentance look like for you, here and now? Where is God leveling the ground you stand on, and what will it take for you to participate in that uncomfortable but essential work?

Comfort awaits us in the desert. God promises to come to us in the wilderness. May we believe this. May we wander and be found. Like the prophets who came before us, may we become brave voices in hard places, preparing the way of the Lord.

Debie Thomas: debie.thomas1@gmail.com

Image credits: (1) Missale.net; (2) AdventDoor.com; (3) Art Is Hard; and (4) www.1stdibs.com.