From Our Archives

Debie Thomas, I Have Longed (2022); Debie Thomas, The Way of the Hen (2019); Edwina Gateley, "Do Not Be Afraid," (2013); and Pam Fickenscher, Don't Fear the Thief (2010).

This Week's Essay

Luke 13:31, "Herod wants to kill you."

For Sunday March 16, 2025

Second Sunday in Lent

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Psalm 27

Philipians 3:17-4:1

Luke 13:31-35

The Nobel laureate Thomas Mann once observed that "in our time the destiny of man presents its meanings in political terms." In other words, there's little meaning outside of politics. There's no other narrative. We have no destiny that is not political. Consequently, the apolitical person is disparaged as disengaged, irrelevant or unpatriotic.

That sort of thinking is as powerfully prevalent today as it was a hundred years ago with Mann, and it's precisely what the readings this week repudiate. They remind us that however important politics and presidents are, the people of God see a bigger picture. They form an alternate community, tell different stories, have a bigger vision, and imagine a greater destiny.

In Luke 13:31, the Pharisees warn Jesus, "You better get out of here, Herod wants to kill you." Eventually, this is what happened, when Jesus was tried and executed before Herod in Luke 23. This warning came at the end of his life, and it's virtually identical to another one at the beginning of his life, when Joseph had a dream in which angels warned him to take his baby and flee to Egypt, for "Herod wants to kill him." (Matthew 2:13).

The name Herod is mentioned nearly 50 times in the New Testament. In fact, there are six different Herods, and they all work to make the subversive kingdom of God subservient to the political power of the state. But all these Herods, whether ancient or modern, are right about one thing; if Jesus is Lord, then caesar is decidedly not lord.

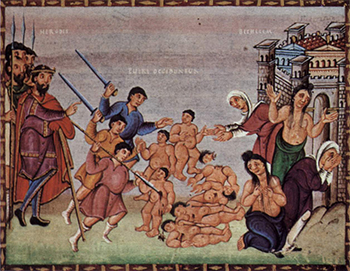

The death threat at the birth of Jesus came from Herod the Great, who slaughtered the children of Bethlehem. The threat in Luke 13 was made by his son Herod Antipas, who murdered John the Baptist. There's a third death threat to Jesus from Herod Archelaus in Matthew 2:22. Herod King Agrippa arrested early believers, executed James, and imprisoned Peter. His son Herod Agrippa II interrogated the prisoner Paul. Finally, there's Herod Philip the Tetrarch in Mark 6:17.

|

|

Herod the Great's Massacre of the Innocents, 10th century "Codex Egberti".

|

And so, a simple but important point that we can extrapolate from the six Herods — from beginning to end, from his birth to his death, there was a deep antagonism between Jesus and the political powers of his day. These Herods disabuse us of any romantic notions about politics. They remind us that the life of Jesus was embedded in the realpolitik of his day.

Luke's gospel this week is the most famous encounter. Herod Antipas was not a man to be trifled with. Nonetheless, despite the warning from the Pharisees that Herod wanted to kill him, Jesus responded with a dismissive insult: "go tell that fox that nobody will stop me from fulfilling my mission in Jerusalem." He mocks Herod as a weaselly poser or pompous pretender.

Jesus threatened the political powers, not because he sought to control what they controlled, says the historian Garry Wills, but because "he undercut its pretensions and claims to supremacy." This becomes even more obvious if we fast forward to the end of Lent and the arrest of Jesus. Today we hear this as a religious story, but in its own day it was explicitly political.

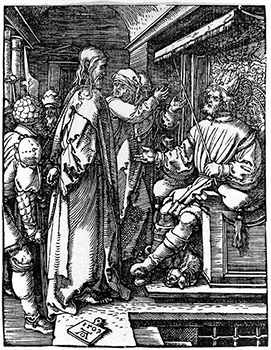

Jesus was dragged before Pontius Pilate and then Herod Antipas for three reasons, all of them political: "We found this fellow subverting the nation, opposing payment of taxes to Caesar, and saying that He Himself is Christ, a King." (Luke 23:1–2). Simply put, he was an enemy of the state.

Pilate met the angry mob outside the praetorium, then grilled Jesus alone back inside. "Are you the king of the Jews?"

"My kingdom is not of this world," Jesus replied. "My kingdom is from another place."

"You are a king, then!" mocked Pilate.

"Yes, you are right in saying that I am a king."

Pilate then had his soldiers beat, flog, and humiliate Jesus with purple robes and a crown of thorns befitting a man whom he miscalculated was a political upstart: "Hail, O king of the Jews!"

Back outside, the mob hounded Pilate: "If you let this man go, you are no friend of Caesar. Anyone who claims to be a king opposes Caesar." Pilate thus found himself caught between angering the mob and betraying his emperor.

He caved in: "Here is your king. Shall I crucify your king?"

"We have no king but Caesar!" And with that response we have an ancient version of Mann's observation that there is no destiny or meaning outside of the political status quo. As Daniel Berrigan put it in his commentary on 1 Kings, there's one and only one political imperative: extra imperium nulla salus, "outside the empire there is no salvation."

|

|

Jesus Before Herod Antipas, Albrecht Dürer, 1509.

|

In the epistle this week, Paul says that he gave us a "pattern" and "example" to follow, namely, that "our citizenship is in heaven." Once again, today we hear this as a religious phrase, but in Paul's day it was overtly political. The language sounds pious in the worst sense of the word, that believers are "so heavenly-minded they're no earthly good." But for Paul the implications were more political than spiritual.

In his commentary on Acts, the Yale historian Jaroslav Pelikan observed that pagans accused the earliest believers of sedition because of the overt political implications of their confession of a "kingdom of God" and a "citizenship in heaven." By confessing Jesus as Lord, they rejected caesar as king. Loyalty to Christ the king was absolute and unconditional, whereas fidelity to the Roman state was relative and conditional.

Finally, there is Abraham. Genesis 15 describes how his descendants would live for four hundred years as "strangers in a country not their own." This language of "resident aliens" was echoed by New Testament writers to describe believers. If Jesus said that his kingdom was "not of this world," then his followers were "aliens and strangers" in this world — Ephesians 2:9, Hebrews 11:13, 1 Peter 2:11.

The Epistle to Diognetus (c. 130) puts this perfectly: the Christians "dwell in their own countries, but simply as sojourners. As citizens, they share in all things with others, and yet endure all things as if foreigners. Every foreign land is to them as their native country, and every land of their birth as a land of strangers."

The political theorist Michael Walzer of Princeton makes a simple observation in his book In God's Shadow; Politics in the Hebrew Bible (2012). He argues that while the Hebrew Bible contains a lot about politics, it isn't really interested in politics. Rather, it presents us with a radical anti-politics. Since God is sovereign, caesar is secondary.

The prophets, for example, are poets of social justice and the most important form of public speech in Israel, but they're not political activists with any program. With their emphasis on divine intention as opposed to human wisdom, the prophets exemplify the Hebrew Bible's "radical denial of the doctrine of self-help." The prophets "disdain" politics. In contrast to Greek philosophers, "the Biblical writers never attach great value to politics as a way of life." Politics is simply "not recognized by the Biblical writers as a centrally important or humanly fulfilling activity."

|

|

Herod Archelaus, in the 1493 Nuremberg Chronicle

|

For example, the political panorama of 1–2 Kings includes the reigns of forty kings and one queen (Athaliah) in the 400 years from the death of David to Israel's exile to Babylon. Only two kings received unqualified approval by the narrator (Hezekiah and Josiah). With rhetorical regularity, over thirty times the narrator renders the ominous judgment that a king "did evil in the eyes of the Lord." Instead of glorifying political power, this 400-year history of politics is unremittingly negative — in keeping with the dire warning in 1 Samuel 8. That's remarkable when you consider that these are Israel's sacred writings, and that such negative conclusions about royal power must have put the author at some risk.

In place of a radically relativized politics, says Walzer, the Hebrew Bible commends an ethic or way of life. Micah 6:8 comes to mind: do justice, love kindness, walk humbly with your God. Speak out for those who have no voice. Protect the weak, feed the poor, free the slaves, and welcome the alien. The sovereign God calls each one of us to a larger community that's characterized by "fellow feeling." That is, we trust ourselves to God alone and are responsible for each other.

Garry Wills uses the same language in his book What Jesus Meant. He writes, "the program of Jesus's reign can be seen as a systematic antipolitics." There's no such thing as a "Christian" politics, he says, and efforts by both Democrats and Republicans (or any other party) to co-opt Jesus for their cause distort the gospels.

The Jesus of the gospels, says Wills, proposes no political program, but instead something far more strenuous, something "scary, dark and demanding." No state or political party can indulge in the self-sacrifice that Jesus demands when he calls us to lovingly serve the least and the lost. But self-sacrificing love for my neighbor is precisely the message of the Lenten season.

Weekly Prayer

Daniel Berrigan (1921–2016)

I can only tell you what I believe; I believe:

I cannot be saved by foreign policies.

I cannot be saved by the sexual revolution.

I cannot be saved by the gross national product.

I cannot be saved by nuclear deterrents.

I cannot be saved by aldermen, priests, artists,

plumbers, city planners, social engineers,

nor by the Vatican,

nor by the World Buddhist Association,

nor by Hitler, nor by Joan of Arc,

nor by angels and archangels,

nor by powers and dominions,

I can be saved only by Jesus Christ.

Dan Clendenin: dan@journeywithjesus.net

Image credits: (1) Wikimedia.org; (2) Wikimedia.org; and (3) Wikipedia.org.