From Our Archives

For earlier essays on this week's RCL texts, see Dan Clendenin, War No More (2022); Debie Thomas, On Behalf of Everyone (2019) and then the essays by Dan Clendenin, To Convert, Begin Now (2016); "I Am Giving Thee Worship with My Whole Life," (2013); The Last and Best Word (2010); and The Last Sentence of the Bible (2007).

This Week's Essay

Acts 16:26, "All the doors were opened, and everyone's chains were unfastened."

For Sunday June 1, 2025

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Psalm 97

Revelation 22:12–14, 16–17, 20–21

John 17:20–26

We were in the highlands of the Republic of Georgia on a muddy spring day in 2021. Georgia was one of the only places in the world that was accepting tourists in the second year of the pandemic, so we wore our masks and went. My husband and I had always wanted to go to Georgia because we had both been students at Kuban State University in the early 1990s in southern Russia. We’d gazed at the towering snowy peaks of the Caucuses Mountains from the north and longed to see them from the Georgian side on the south.

We took a group tour van up to the remote village of Ushguli in the Svaneti region and wandered around the streets in the rain. Wet and cold, we piled into a local cafe for steaming bowls of dumplings. We were joined at a long wooden table by two young Russian artists.

|

|

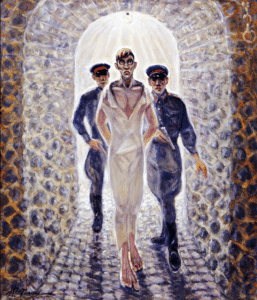

In the NKVD's Dungeon" by Ukrainian artist and gulag survivor Nikolai Getman (1917–2004), who spent eight years in Siberia.

|

We talked about their lives and the conditions that they found themselves in under Vladimir Putin’s regime. “Jail,” they said half jokingly, “is where we go to network.” One of them remarked, “We tell each other, ‘If you haven’t been to jail recently, you don’t love your country.’” They told half-funny and half-tragic tales of being freed from jail under a variety of circumstances, sometimes for reasons they could only vaguely understand, sometimes through connections with random people in power. They were in a system that didn’t make sense, they knew it, and they’d decided to respond with fearlessness. At that time, going to jail was a way that they could disrupt state power and contest its constant surveillance and harassment of them. They could turn the state’s attempts to control them into a form of protest.

This was less than a year before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine; three years before Alexei Navalny was murdered in prison; and three years before the torture and death of Ukrainian war journalist Viktoriia Roshchyna. I’ve thought of the couple we met in Georgia often since. I wonder if they fled Russia or if they were conscripted to the front lines. I wonder if they, like so many other Russian artists and intellectuals, are living in Armenia or Georgia or Kazakhstan. I wonder if they are in prison.

I thought of them again as I watched students and random residents in my own country picked up, detained, and imprisoned in acts of state power that were uninterested in justice or law or due process.

This week’s lectionary text from Acts starts with a slave girl who is described as being enslaved both by owners — who dictate her actions and her value — and by an inner spirit that tells her what to do and what to say. This image of a person lacking in both interior and exterior freedom is contrasted with Paul and Silas. They have inner freedom, but when they use this inner freedom to rebuke the system that enslaves her, they are also caught up in that system and sent away to “the innermost cell” of the jail (Acts 16:24).

|

|

"Escape" by Nikolai Getman (1917–2004).

|

They are arrested, not because they had done something wrong, but because they had gone against the economic interests of people in power. These people say in essence, “Don’t shine a light on our corruption. Don’t interfere with the good thing we’ve got going here.” We see the arbitrariness of this concept of law — how what is lawful is determined by what those in power find expedient.

And we observe how those with less power are made to do the bidding of the powerful. The mob acts as an enforcer. And like Hitler’s willing executioners, others, like the jailer, are drawn in by “just doing their jobs.”

This is the context in which we are led to observe Paul and Silas’s inner freedom. The songs that they sing, for example, while imprisoned: I imagine the almost haunting sound of these songs coming from that innermost cell. And then, when they are mysteriously freed from their chains, along with everyone else in the prison, they don’t run away. They choose to stay, demonstrating that their freedom ultimately has little to do with walls and chains.

I find these same dynamics of inner and outer freedom mirrored in a composite and metaphoric form in Psalm 97. We begin with “clouds and thick darkness” (97:2), a time of uncertainty, the way forward not clear. Then there are flashes of light, “lightenings that light up the world” (97:4), but only for a moment, before returning to darkness yet again. We begin to see how another order exists beyond the one that is being run by “those who make their boast in worthless idols” (97:7). We begin to sense that the law of freedom is found in this alternative, a place where we are rescued from those who would lock us up. This is how “light dawns” (97:11), and the day comes slowly. Unlike the flashes of light, the dawning inner light grows and sustains us.

|

|

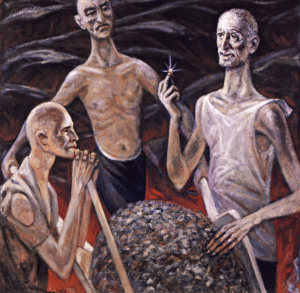

"Yakutsk Diamonds" by Nikolai Getman (1917–2004).

|

I’ve been reading Nadezhda Mandelstam’s account of the last days of her husband — the imprisoned poet Osip Mandelstam — during the Stalinist Reign of Terror. She describes a tyrannical social system designed to imprison people, whether or not they were ever literally sent to prisons, labor camps, or into exile. Neighbors were compelled by fear to report on their neighbors. Everyone was listening in on everyone else and wondering who would betray them.

As she reflects on how this kind of psychological pressure makes people respond, she sees in Osip an inner freedom that no amount of pressure can break. This freedom is rooted in love and in careful observation of the world around him, in a sense that his own inner life, expressed in his poetry, is more powerful than any political force. While the cruelty and deprivation of the labor camp finally broke him physically, he wrote poetry until the very last days of his life.

Weekly Prayer

Osip Mandelstam (1891-1938)

And I was alive in the blizzard of the blossoming pear,

Myself I stood in the storm of the bird–cherry tree.

It was all leaflife and starshower, unerring, self–shattering power,

And it was all aimed at me.What is this dire delight flowering fleeing always earth?

What is being? What is truth?Blossoms rupture and rapture the air,

All hover and hammer,

Time intensified and time intolerable, sweetness raveling rot.

It is now. It is not.(May 4, 1937)

Translated by Christian Wiman

Osip Mandelstam (1891–1938) was a Russian poet and essayist who lived during and after the revolution and the rise of the Soviet Union. He died in a labor camp in 1938. This is believed to be one of the last poems he wrote. From Stolen Air: Selected Poems of Osip Mandelstam, selected and translated by Christian Wiman (CCCO, 2012), p. 71.

Amy Frykholm: amy@journeywithjesus.net

Image credits: (1–3) Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation.