From Our Archives

Debie Thomas, Down from the Mountain (2022); Debie Thomas, Lights and Shadows (2019); and Debie Thomas, The View from the Valley (2016).

This Week's Essay

Luke 9:40, "I begged your disciples to heal my son, but they could not."

For Sunday March 2, 2025

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Psalm 99

2 Corinthians 3:12-4:2

Luke 9:28-36, (37-43a)

This week brings us to the last Sunday in the season of Epiphany. It began after Christmas with the adoration of the pagan magi, bearing their gifts to the baby Jesus. It now ends before Lent with the transfiguration of Jesus, when the disciples "saw his glory" on the mountain.

The Greek word epiphaneia means disclosure, manifestation, unveiling or appearance. So, it's appropriate that Luke 9:28–36 for this week describes one of the greatest "epiphanies" ever — the transfiguration, transformation, or metamorphosis of Jesus, complete with blinding light, a heavenly voice, and visions of Moses and Elijah. The transfiguration of Jesus was so central to the gospel tradition that all three synoptic writers include it (Matthew 17:1–8 = Mark 9:2–10 = Luke 9:28–36).

28 About eight days after Jesus said this, he took Peter, John and Jameswith him and went up onto a mountain to pray. 29 As he was praying, the appearance of his face changed, and his clothes became as bright as a flash of lightning. 30 Two men, Moses and Elijah, appeared in glorious splendor, talking with Jesus. 31 They spoke about his departure,[a] which he was about to bring to fulfillment at Jerusalem. 32 Peter and his companions were very sleepy, but when they became fully awake, they saw his glory and the two men standing with him. 33 As the men were leaving Jesus, Peter said to him, “Master, it is good for us to be here. Let us put up three shelters — one for you, one for Moses and one for Elijah.” (He did not know what he was saying.) 34 While he was speaking, a cloud appeared and covered them, and they were afraid as they entered the cloud. 35 A voice came from the cloud, saying, “This is my Son, whom I have chosen; listen to him.” 36 When the voice had spoken, they found that Jesus was alone. The disciples kept this to themselves and did not tell anyone at that time what they had seen.

Decades after the transfiguration, 2 Peter appealed to this terrifying experience precisely to rebut criticisms that the early believers followed "cleverly invented stories." No, he says, they gave "eyewitness" accounts of actual events (2 Peter 1:16–18), even if the story, like so many stories in the gospels, was easier to describe than to explain.

Such is the ecstasy.

|

|

Healing of a boy with epilepsy, Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, 15th century.

|

But then comes the agony. In all three versions of the transfiguration, after going "up the mountain" for the ecstasy, "the very next day" the disciples "came down from the mountain," where they encountered a distraught father with an epileptic son. I still remember decades ago seeing a man have an epileptic seizure. I recently felt like the frightened father — my son had a seizure caused by a bike crash that landed him in a trauma center. An epileptic seizure is terrifying, and the gospel describes it perfectly: screaming, convulsions, rigidity, grinding teeth, and foaming at the mouth.

This encounter between the disciples and the father ended in failure — "he's my only child, and I begged your disciples to heal him but they could not." Then, when Jesus explained to them (yet again) his destiny of betrayal, suffering, and death, "they did not understand what this meant. It was hidden from them, so that they did not grasp it, and they were afraid to ask him about it."

They couldn't heal. They didn't understand. They were afraid.

So, the epiphany of the transfiguration was followed by hiddenness. The powerful disclosure resulted in ignorance, fear, and failure. In the Matthew 17 and Mark 8 versions of this story, despite the unveiling, there is also a command of secrecy: "Jesus gave them orders not to tell anyone what they had seen." What's the purpose of an epiphany if you are sternly warned to keep it a secret?

And finally, a bitter irony — after they failed to heal the little boy, in Luke's very next story, the disciples argued among themselves about who was the greatest, and bragged about preventing an exorcist from healing people. Really?!

This week I also felt like the disciples. I couldn't heal. I didn't understand. I failed to see anything redemptive. Our neighbors have a toddler who was born with a rare and dreadful genetic skin disorder called epidermolysis bullosa. She just spent seventeen days in the ICU after she suddenly stopped eating and drinking, and started having dramatic outbursts. Her doctor is one of the best specialists in the country, and also a deeply compassionate man. But like the distraught father watching his child have a seizure, begging in vain for healing, the parents are understandably overwhelmed with pain and fear. And like the disciples, I felt useless and helpless in the presence of a suffering child.

|

|

Healing of the epileptic boy, the Jruchi Gospels II, National Center of Manuscripts, Tbilisi, Georgia (1667).

|

It would be nice if we could "bottle the lightning" of a transcendent experience like the transfiguration so that we could eliminate our fears, our failures, our pain and ignorance. But that's not how life works. Nor is it what we see in the gospels. "Listen carefully," Jesus told the disciples in the very midst of the transfiguration, "betrayal, suffering, and death await me in Jerusalem."

In Acts 9, Paul was blinded by a flash of light on the Damascus road. His dramatic encounter with the divine truly altered western history. But that "epiphany" did not lead to perfection. Paul remained notably circumspect about our mortal lives. He wrote of his "conflicts without and fears within." Notwithstanding the divine light, we only see "through a glass darkly." Whatever was "unveiled," we still know "only in part." Our groanings are "too deep for words." We "don't know how to pray," says Paul. We don't understand our deepest desires (Romans 7:14ff). In contrast to the pseudo-apostles in 2 Corinthians who made fantastic claims, Paul would only "boast about my weaknesses." The heavenly treasure is held in earthly "jars of clay."

|

|

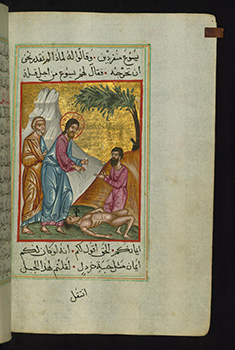

Healing of the epileptic boy by the Coptic monk Ilyas Basim Khuri Bazzi Rahib, c. 1684.

|

In Acts 10, Peter had a visionary "disclosure" in which God commanded him to eat unclean animals. Although the Jewish purity laws forbid him to associate with "dirty" Gentiles, he came to the radical conclusion that "God has shown me that I should not call any man impure or unclean. I now realize how true it is that God does not show favoritism." But despite this powerful epiphany, Peter later back tracked, and lapsed into hypocrisy by refusing to eat with Gentiles, and so Paul publicly rebuked him (Galatians 2:11). Peter's transfiguration was followed by failure.

In 2 Corinthians 3 for this week, Paul compares and contrasts two transfigurations — that of Moses in Exodus 34, and the transfiguration of Jesus. Even though the face of Moses shown with radiance and glory, I resonate with Paul's description of the Israelites. He says that "their minds were made dull," and that "a veil covered their hearts." However brilliant the light, it was nonetheless "fading." How true even today.

But Paul also concludes with an invitation and a promise. He uses the same word for us that the gospels use for Jesus. Just as Jesus experienced a metamorphosis on the mountain (Mark 9:2), Paul says that we too experience our own metamorphosis (2 Cor. 3:18) when, bit by bit, we behold the glory of God.

For now our metamorphosis is partial and imperfect, just like it was for the disciples. After all, it is only Epiphany. But Easter is out there on the horizon, signaling that one day "the veil will be taken away," finally and fully and forever, and then we will see God face to face.

Weekly Prayer

Christian Wiman (b. 1966)

Prayer

For all

the painpassed down

the genesor latent

in the very grainof being;

for the lordlessmornings,

the smearof spirit

words intuitand inter;

for allthe nightfall

nevernessinking

into meeven now,

my prayeris that a mind

blurredby anxiety

or despairmight find

herea trace

of peace.From Once in the West: Poems (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2014).

Christian Wiman is the author, editor or translator of more than a dozen books of poetry and prose. He teaches religion and literature at the Yale Institute of Sacred Music and at Yale Divinity School. His most recent book is Zero at the Bone: Fifty Entries Against Despair (2023).

Dan Clendenin: dan@journeywithjesus.net

Image credits: (1) Wikimedia.org; (2) Wikimedia.org; and (3) Wikimedia.org.