From Our Archives

Debie Thomas, Today (2022); Debie Thomas, When He Opened the Book (2019); Dan Clendenin, One Body, Many Parts (2013); and Sara Miles, Today is Here (2010).

This Week's Essay

For Sunday January 26, 2025

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Psalm 19

1 Corinthians 12:12-31a

Luke 4:14-21

The gospel for this week has given me a serious case of spiritual whiplash. Luke's story begins with an adoring crowd, but then it ends with a violent mob. In Luke, this is the first public appearance of Jesus, after a longish introduction about his genealogy, birth, baptism, and temptation. What is Luke telling us with such a dark and dramatic reversal at the beginning of his gospel?

As the rumors about Jesus spread throughout "the whole countryside," writes Luke, "everyone praised him." A few verses later, he repeats himself: "All spoke well of him and were amazed at his gracious words." This echoes what he has already said about the shepherds, who were "amazed" at the things being said about the baby in the manger, and Mary and Joseph who were "astonished" at the boy Jesus in the temple.

The story for this week takes place in Nazareth, "where Jesus had been brought up." So, he was among his friends and family who had known him for thirty years. He was simply "Joseph's son" in a village of about 500 people. In particular, Luke says four times that this story takes place in the synagogue, the literal and symbolic epicenter of Jewish religious and political identity.

On the sabbath day, Jesus went to the synagogue "as was his custom." He then did something strange and enigmatic. He took the scroll of Isaiah 61, read it out loud, and then said that he himself — this ordinary hometown carpenter, was the embodiment of Isaiah's messianic promise to bring God's good news to the poor, the prisoners, the blind, and the oppressed." He came to "proclaim God's favor" to everyone. No wonder the hometown crowds were amazed and astonished.

|

|

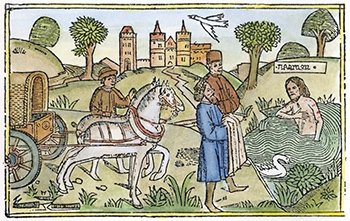

Namaan the Syrian, The Cologne Bible, 1478-1480.

|

But Jesus deflected their adoration, much as in John 2:24 when "he did not trust himself" to the crowds even though they believed in him and his miracles. He looked beyond the superficial excitement. His hometown of Nazareth knew about his miracles in Capernaum some thirty miles away. And perhaps there was a tinge of jealously and envy, for Capernaum was Jesus's second home and where he lived as an adult. Jesus acknowledged what had remained unspoken, that Nazareth wanted their own miracles, just like Capernaum, especially after he had identified himself as the miracle worker of Isaiah 61.

Then comes the whiplash. Yes, you will see miracles, says Jesus, but they will be for the pagan outsider Gentiles rather than for you chosen insider Jews. He then gave two examples — from their own Hebrew Scriptures, no less! — about how God had blessed two impure and unclean Gentiles — a destitute widow in Zarephath in the region of Sidon, whose son was raised from the dead (1 Kings 17), and Naaman the military commander of enemy Syria, who was healed from leprosy (2 Kings 5). Even worse, these two stories featured their national "heroes" Elisha and Elijah.

At this point, the superficial praise turned to violent hostility. "All the people in the synagogue were furious when they heard this. They got up, drove Jesus out of the town, and took him to the brow of the hill on which the town was built, in order to throw him down the cliff." One translation says that the crowd was "filled with rage." They tried to kill Jesus.

Luke is the only Gentile author in the Bible, so he has some skin in this game. Whereas the very first sentence of Matthew calls Jesus "the son of David, son of Abraham" — a quintessential Jew, Luke's genealogy describes him as "the son of Adam" — that is, Jesus is not just the king of the Jews, he's the son who represents all of humanity.

|

|

Samaritan woman at the well, 6th century mosaic, Ravenna, Italy.

|

For Jesus, the election of the Jews did not mean the exclusion of the Gentiles. Throughout the gospels, the Jewish Jesus embraced the unclean Gentiles — the Roman centurion, the Canaanite woman and her demon-possessed daughter, and Samaritans like the leper in Luke 17, the woman at the well in John 4, and the good Samaritan of Luke 10.

He was similarly dismissive about religious orthodoxies and litmus tests. Ritual purity? Jesus "declared all foods clean." Keeping the sabbath? "The sabbath was made for man, not man for the sabbath." And the sanctity of the synagogue? Jesus desecrated the temple and called it a "house of prayer for all nations." The religious gatekeepers complained that his disciples ate with "unwashed hands," and derided him as a glutton and drunkard who befriended "dirty" people. They were more right than they knew.

My takeaways from Luke's strange story are twofold.

First, I'm reminded of our perennial temptation to sanitize and sentimentalize Jesus. We're forever trying to domesticate the deity. Yes, Jesus inspires, but he also infuriates. In her memoir Reading Jesus, the literary critic Mary Gordon calls Jesus the "irresistible incomprehensible." He is the stone that makes us stumble, the rock of offense. No wonder that John reported how "many of his disciples turned back and no longer followed Jesus," and that his own family did not believe in him, but rather tried to apprehend him as insane. There is a sort of admirable honesty in leaving Jesus.

Similarly, in his book What Jesus Meant, the historian Garry Wills says that "what Jesus signified is always more challenging than we expect, more outrageous, more egregious." For Wills, Jesus was a homeless "man of the margins." Jesus is a sign of contradiction and a threat to political power who in his mission as the Son of God "took up the burden of all humankind" — not just for the elect Jews. Even if scholars found the "true and original" Jesus "behind" the Bible texts, says Wills, he would appear more rather than less incomprehensible to us.

|

|

The Gentile magi with Jesus, 3rd-century sarcophagus, Rome.

|

My second takeaway comes from Jesus's examples of the widow of Zarephath and Namaan of enemy Syria. As Wills observes, Jesus saved his harshest criticisms for those self-appointed gatekeepers who wanted to exercise spiritual authority over others and claim insider status. He regularly broke religious rituals, mocked external purity, and violated social taboos to demonstrate that God in his lavish and indiscriminate love never excludes people because they are unclean, unworthy, or unrespectable: "No outcasts were cast out far enough in Jesus's world to make him shun them." In short, concludes Wills, "tremendous ingenuity has been expended to compromise these uncompromising words. Jesus is too much for us."

So, beware of the flannel graph Jesus. It might offend the religious insiders, but Jesus came to include the outsiders in God's love. In 2025, to quote Rilke, let us live our lives "in ever-widening circles, that reach out across the world, each one bigger than the last one," for it's on the spiritual fringes, in places like Elijah's Sidon and Elisha's Syria, that we just might experience the miracles that we say we want Jesus to perform for us.

Weekly Prayer

"To Saint Peter Claver"

Daniel BerriganHeal us Jesuits; the overly content, the malcontent,

the skilled and sere of heart, the secret weepers,

the self-defeated, the defaulters, the proud of place

drinking the empty wind of honor. Help the workhorses

slow; speed the laggards, give back to routine and rote

their lost soul.

Institution, constitution, order, law—O

kiss the dead awake!

Your Holy Spirit, come!From Daniel Berrigan, And the Risen Bread; Selected Poems, 1957–1997 (1998). From Wikipedia: "Saint Peter Claver (1581–1654), S.J., was a Spanish Jesuit priest and missionary born in Verdú who, due to his life and work, became the patron saint of slaves, the Republic of Colombia and ministry to African Americans."

Dan Clendenin: dan@journeywithjesus.net

Image credits: (1) Amazon.com; (2) WilliamBryantLogan.com; and (3) Wikipedia.org.