"They Say There's Another King, One Called Jesus"

For Sunday November 24, 2013

The Celebration of Christ the King

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Jeremiah 23:1–6

Luke 1:68–79 or Psalm 46

Colossians 1:11–20

Luke 23:33–43

For Roman Catholics and churches that follow the Revised Common Lectionary, this last Sunday of the liturgical year honors "Christ the King." It's a relative newcomer to the Christian calendar. Pope Pius XI introduced the feast on December 11, 1925 with his encyclical "Qua Primas" (In the first). That papal letter summarizes the Bible's teachings about the kingship of Christ.

According to Pius, Christ the King rules not only over the church, but over all the whole world — if not now, then at the end of time.

|

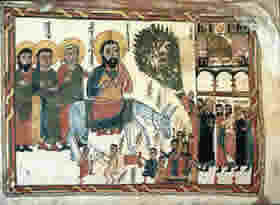

Jesus's Triumphal Entry, Medieval Syriac manuscript. |

Doesn't this feel like a setup for liturgical failure? For the worst sort of triumphalism? If so, blame Paul and not Pius.

Today the language of kingship is outmoded and offensive. There are good reasons for this. We don't live under kings, so the metaphor feels irrelevant. And we're rightly repulsed at how the reigns of kings meant a reign of terror for most subjects — massive wealth and power attained by cruelty and exploitation, which was then passed on by birthright to people who did nothing to deserve it.

Nonetheless, the language of kingship is embedded in the Christian story. The earliest followers of Jesus, and especially his detractors, used the language of kingship to describe who he was, what he said, and what he did.

Unless you want to follow Thomas Jefferson, and snip and clip the parts of the Bible that you don't like — creating a Bible in your own image, we're left with the language of kingship.

As in the game of golf, we're better off to play the Scriptures where they lie. The question then becomes what kingship means.

In the epistle for last week, Paul wrote to the church at Thessalonica (see Acts 17:1–8). His ministry there started in the local synagogue, then expanded to include "a large number of God-fearing Greeks and not a few prominent women."

Then came the detractors. Their accusations have the suspicious sound of historical reliability. A mob complained to city officials that the believers "defied Caesar's decrees" by saying that "there is another king, one called Jesus." Thessalonica erupted in riots.

Civic-minded Romans accused the early believers of sedition because of the overt political implications of their confession of "another king," a "kingdom of God," and a "citizenship in heaven." If Jesus is Lord and King, then allegiance to him is absolute and unconditional. Political heresy then follows — Caesar, Herod, Pharaoh, Pilate, and Mammon are not lords. At best, our allegiance to them is relative and conditional. At worst, they are posers to be deposed.

In the gospel for this week from Luke 23, Jesus is dragged to the Roman governor's palace for three reasons, all political: "We found this fellow subverting the nation, opposing payment of taxes to Caesar, and saying that He Himself is Christ, a King." Jesus died as a politically subversive criminal; his followers were subversive citizens.

Pilate met the angry mob outside the praetorium, then grilled Jesus alone back inside. "Are you the king of the Jews?"

"My kingdom is not of this world," Jesus replied. "My kingdom is from another place."

"You are a king, then!" mocked Pilate.

|

Mosaic of Christ before Pilate, Basilica of Saint Apollinare Nuovo, 6th century. |

"Yes, you are right in saying that I am a king."

Pilate went back outside, declared that Jesus was innocent, then had his soldiers beat, flog, and humiliate him with purple robes and a crown of thorns. "Hail, O king of the Jews!" they mocked.

Back outside, the mob hounded Pilate: "If you let this man go, you are no friend of Caesar. Anyone who claims to be a king opposes Caesar." Pilate thus found himself sandwiched between angering the mob and betraying his emperor.

He caved in: "Here is your king. Shall I crucify your king?"

"We have no king but Caesar!"

Pilate insulted the Jews one last time by fastening a notice to the cross, written in Aramaic, Latin, and Greek, which he knew would offend them: "Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews." They objected, of course: "Don't write 'The king of the Jews,' but that this man claimed to be king of the Jews."

It was too late: "What I have written, I have written," said Pilate. With his mockery of the Jews, Pilate wrote much more than he ever could have known or imagined.

Later believers would worship Jesus not only as king of the Jews, but also as "the king of kings" (1 Timothy 6:15, Revelation 19:16), the "king of the ages" (Revelation 19:3), and "ruler of the kings of the earth" (Revelation 1:5). But even all that doesn't plumb the depths of the full Christian confession.

If the language of kingship in the gospel offends us, the epistle to the Colossians makes your head explode.

It's impossible to reconstruct two thousand years after the fact, but it seems like the church at Colossae faced a syncretistic mishmash of spiritual teachings. Paul mentions philosophic speculations, ascetic practices about food and drink, and religious rituals based upon the lunar calendar or the Jewish sabbath. All these, Paul says, are a mere "shadow" compared to the "reality" that we experience in Christ.

Jesus wasn't just the son of a carpenter, says Paul, an itinerate rabbi, or a rogue "king" who angered Rome. He's not even merely "the head of the church." Yes, he's all these, but he's far more.

Cucifixion icon, Sinai, 8th century. |

The Colossian confession makes the language of kingship look pale and puny by comparison. For Paul, Jesus is the Lord of all creation and cosmos, whether "things in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or powers or rulers or authorities."

The other readings this week fill out this picture of Christ the king and Lord of the cosmos. He's the one who gathers rather than scatters (Jeremiah 23). Instead of waging war, "he makes wars cease to the ends of the earth; he breaks the bow and shatters the spear, he burns the shields with fire." (Psalm 46:9). Jesus the king welcomes the criminals (Luke 23:43).

In the mission and message of Jesus, says Paul, God will "reconcile to himself all things, whether things on earth or things in heaven." Peace and reconciliation for all of creation, not domination and exploitation, are thus signs of the kingdom of God in Jesus.

So don't blame Pius. Thank Paul, who wrote to the Colossians, "This is the gospel that you heard and that has been proclaimed to every creature under heaven."

Image credits: (1) Christopher Haas, Department of History, Villanova University; (2) Robert W. Brown, Dept. of History, University of North Carolina Pembroke; and (3) Jugoslav Ocokoljić.