For Sunday April 10, 2022

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Isaiah 50:4-9a

Psalm 31:9-16

Philippians 2:5-11

Luke 22:14-23:56 or Luke 23:1-49

My essay this week focuses on the Passion Sunday readings. If you’d like to read essays based on the Palm Sunday texts, here are two from our archives:

Sorrow and Love Flow Mingled Down: Palm Sunday

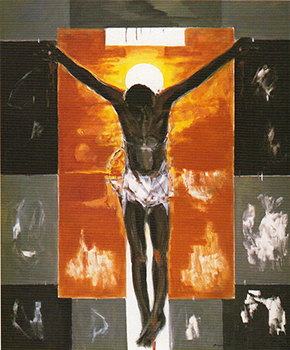

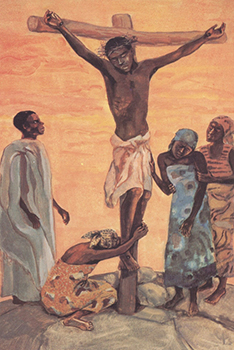

The longer I practice my faith, the more essential and all-encompassing Jesus’s Passion becomes. With each year that goes by, I feel pulled in the direction of the cruciform — the cross-shaped, the cross-centered, the cross-infused. Which is to say, I’m drawn to a God who suffers before he conquers. A bruised God who accompanies as well as saves. In short, I’m increasingly reliant on the painful mystery we call “Good” Friday: it is in dying that we will live. It is in surrendering that we might triumph. It is in the shape of a lonely, jagged cross that we'll find the salvation of intimacy with God.

In many ways, Holy Week holds within it our entire human story — all of the hope, tragedy, love, and joy that shapes our days. It reveals to us the horrors of injustice, but it also shows us the deepest love the world has ever seen. As we move from the intimacy of the Last Supper, to the agony of Gethsemane, to the desolation of Golgotha, we can find traces of our own stories — stories of friendship and betrayal, fervor and futility, hope and humiliation.

Of course, standing on this side of resurrection history as we do, it’s easy for us to skip past the cross at times, or to soften its sting with sentimentality. It's easy for us to forget that two thousand years ago, Jesus’s death held no religious meaning whatsoever. No veneer of holiness, no hint of redemption, and absolutely no connection to God. For Jesus's first followers, the cross was a state instrument of torture and death. Period. Imagine for a minute if the central symbol of our faith nowadays was an electric chair, or a lethal injection chamber, or a lynching tree.

|

Biblical historians tell us that it was not uncommon for the road to Jerusalem to be lined with crosses in Jesus’s day, each of them bearing a body. Anyone who took that road from their home to the market, or from the market to the temple, or from the temple to a friend’s house, would have no choice but to encounter those grim instruments of capital punishment on a regular basis.

Imagine what life was like for the people who lived in the shadow of those crosses. Imagine how their hopes shriveled under the constant threat and terror. Because of course, that was the point. The crosses were meant to intimidate. The crosses were the Roman Empire’s illustrated sermons, and the message of those sermons was crystal clear: “You can have your religion. You can worship whatever you want. But don’t forget, even for a minute, who really holds sway over your life. Go to your temple if it suits you, call on your God if it makes you feel good, but never, ever mess with the power structures that actually control your world. Don’t even think about resisting. If you do, we’ll hang you up, too.”

We know that the disciples’ great hope was that Jesus would lead them in a military revolution and overthrow their Roman oppressors. Jesus was the one who was supposed to pull down the crosses. Not die on them.

But that is precisely the binary that Jesus challenges when he takes up his cross, and it is precisely the binary we’re called to challenge as well. In a cruciform faith, we can no longer divide “human” things (loss, grief, pain and humiliation), from “divine” things (glory, triumph, invincibility, and power.) On the cross, Jesus insists that God is in the hard things, the low things, the scandalous things. The gritty, messy, broken things. God does not hold God’s self remote from the worst of this world. Immunity and invincibility are our fantasies. They have nothing to do with God.

Think once again about those crosses that lined the road to Jerusalem. Think about the fundamental passivity those crosses were meant to instill in the people who gazed up at them. And then think about Jesus willingly taking up one of those crosses and saying, “I will not stop for you. I will not choose safety at the expense of injustice and evil. I will not save my own skin while you keep killing the people I love."

|

My uncomfortable truth is that I often live in such fear of suffering and death that I use up a huge amount of my mental, spiritual, and physical energy trying to stave off both. To be fair, contemporary western culture encourages me to do this. What would Jesus say, I wonder, to a culture that glorifies violence but cheapens death? What would he say to a global economy that rapes and pillages the planet, instead of stewarding it with tenderness and wisdom? What would he say to a notion of personal liberty that encourages me to insist on my “rights,” while ignoring my civic and spiritual responsibilities?

What would he say to my own frightened heart, that flees from all things cruciform, prioritizing self-protection over everything else that matters in this life?

The cross is not about remaining passive and fearful. The cross is not about admitting defeat. The cross is not about opting out. The cross is about shaking things up. The cross is about rattling the system to its core. The cross is about enduring whatever might happen to us when we confront, resist, and protest the injustices we see around us.

Here and now, the cross is about saying: “It’s not enough that my children are safe on the streets if yours are not. It’s not enough that I have clean air to breathe when my neighbors two towns over do not. It’s not enough that I’ll have dinner to eat tonight if you will not. It’s not enough that my zip code grants me prestige and security while yours does not. It’s not enough that I feel welcomed and nourished by the church if you do not.”

To live a cruciform life is to live in the center of the world’s pain. Taking up the cross means recognizing Christ crucified in every suffering soul and body we encounter, and pouring our energies into alleviating that pain. It means accepting — against all the lies of our culture — that we will die, and following up that courageous acceptance with the most important question we can ask: how shall we spend this one, brief, singular, God-breathed life?

Shall we hoard it in fear, or give it away in hope? Shall we push suffering aside at all costs — and in doing so, push Jesus aside, too? Or shall we live cruciform lives, accompanying the one we call “Savior” down the only road that actually leads to hope and healing?

For those of us who've grown up in the church, the actual scandal and strangeness of Jesus’s death has maybe long faded away. But the bottom line is: God died. Jesus willingly took the violence, the contempt, the apathy, and the arrogance of this world, and absorbed them all into his body. He resisted the powers — terrifying as they were — and in doing so, declared solidarity for all time with those who are abandoned, colonized, oppressed, accused, imprisoned, beaten, mocked, and murdered. He took an instrument of torture and turned it into a vehicle of hospitality and communion for all people, everywhere. He loved and he loved and he loved — all the way to the end.

|

For me, the temptation to resist the cruciform is just about constant. The world tells me all the time that I don’t have to do this hard thing. I don’t have to take this faith business so seriously. I don’t have to engage deeply or take any real risks. I don’t have to die.

It’s true. I don’t. There is a spectator version of Christianity out there, and people do live it. But I can’t pretend that it’s the version Jesus calls me to. I can’t fool myself that standing on the sidelines will grant me immunity, or safety, or meaning, or joy. Because it won’t. On the contrary, it’s death and death alone that leads to resurrection.

Needless to say, none of us live — or can live — the cruciform life perfectly. We get tired. We get overwhelmed. We lose hope. But Holy Week reminds us that our bedrock is not death. Our bedrock is resurrection. Christianity is not masochism. Suffering is not our end goal. The cross is the instrument of solidarity and resistance that carries us from a shallow half-life to the abundant, glorious life of the children of God.

So. As we enter into the drama and pathos of Jesus's last days, let’s remember that the essential question is not, “How badly are we willing to suffer?” The essential question is: “How badly, fiercely, urgently, do we want to live the resurrection?”

Debie Thomas: debie.thomas1@gmail.com

Image credits: (1) Vanderbilt University Library; (2) Vanderbilt University Library; and (3) Vanderbilt University Library.