For Sunday October 22, 2017

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Exodus 33:12-23 or Isaiah 45:1-7

Psalm 99

1 Thessalonians 1: 1-10

Matthew 22: 15-22

For the month of October, Journey with Jesus is "Remembering the Reformation: 500 Years" with guest essays from five traditions: Catholic, Reformed, Anglican, Lutheran, and Orthodox. This week's essay is by Jane Shaw, Dean for Religious Life and Professor of Religious Studies at Stanford University. She is an Episcopal priest who was ordained in the Church of England.

This year we mark the 500th anniversary of the posting of Martin Luther’s 95 theses on the castle door in Wittenberg in 1517. When we think of the Protestant Reformation, we think first of the great reformers and theologians: Luther, Zwingli, and Calvin. But things were rather different in England, where there was no such figure leading the charge. Rather, successive monarchs and parliamentary acts determined the course of the reformation in that country.

This does not mean that the voices of reform had not been heard in England by the time that Henry VIII broke with Rome in the 1530s: the translation of the Bible into English, humanist scholarship, and tracts against the abuses of the late medieval church were all present and lively. Nevertheless, it is the case that the fortunes of those who both resisted and desired Protestant reform were swayed and shaped by the faith of the monarch.

After Henry died in 1547, the short reigns of Henry’s son, the Protestant Edward VI, and older daughter, the Roman Catholic Mary, meant that there was much change in a short period of time. It was only during the long reign of his younger daughter, Elizabeth I (1558 – 1603) that some sense of an enduring reformation and its parameters were established.

So, what was and is the legacy of the Protestant Reformation from an Anglican (or Episcopal) perspective?

|

|

Thomas Cranmer (1544).

|

First and perhaps most obvious is the Book of Common Prayer: this is the liturgy in English, devised and compiled by Henry VIII’s Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer, though he was unable to bring it into use until Edward’s more overtly Protestant reign. While the Protestants in continental Europe fought over matters like how one is saved and the exact meaning of the eucharist, Cranmer thought that all would be well if everyone prayed together, and so he created a prayer book for all to use. The only doctrinal statements to be assented to, for the laity at least, were the creeds of the early church. In this way, the practice of prayer took precedence over the statement of beliefs. Elizabeth I reinforced this idea by saying that she did not wish to make windows into her subjects’ souls.

Cranmer took the traditional monastic offices and reduced them to two — morning and evening prayer — which the parish priest says daily, on behalf of the whole parish, regardless of who is present. A Church of England priest friend of mine tells a story to illustrate this. In his parish in rural Sussex in the 1980s, he would ring the church bell every morning, say morning prayer (often on his own), and then go to buy the newspaper from his village shop. One morning, feeling a bit sick, he skipped the bell ringing and morning prayer, but later went to buy his newspaper. The shopkeeper chastised him: “No bell today, which means you didn’t say morning prayer for all of us.”

This means that, in the Anglican tradition, every day begins and ends with prayers of praise, confession and thanksgiving, the saying of psalms, and readings from the Bible. The beauty of Cranmer’s language, with prayers, known as collects, composed by him, or adapted from Latin or Eastern Orthodox sources or from the work of his contemporary Protestant reformers, has shaped the devotion of many generations across many countries.

As the British expanded their empire and engaged in missionary activity, so they took the Book of Common Prayer with them. By the end of the nineteenth century, the Book of Common Prayer was, as one commentator puts it, at “the height of its career,” translated into numerous different languages. In the twentieth century, it was subject to revisions in many countries, as modern reformers attempted to bring Cranmer’s language and theology up to date, and create worship that was culturally appropriate for their contexts.

|

|

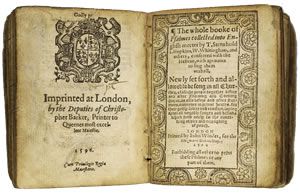

The 1596 Book of Common Prayer.

|

Anglicanism’s distinctive prayer book also gave birth to an extraordinary musical legacy. As early as the sixteenth century, composers started to set the canticles from morning and evening prayer to music, especially the Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis, from the Gospel of Luke, at evening prayer. Thus the tradition of evensong emerged. In cathedrals, parish churches, and college chapels throughout the Anglican Communion, choirs sing evensong to the glory of God daily. As other churches see a decline in attendance, evensong is enjoying a surge in popularity, as people come to appreciate the beauty of the music and liturgy, and of the architectural surroundings too. In England there is even now an app, so that you can find the nearest evensong to you— Choralevensong.org. Step into a cathedral any afternoon of the week, and you can hear music spanning across the centuries, from Thomas Tallis to Herbert Howells to Judith Weir. The enduring significance of evensong reminds us that beauty has always been central to the Anglican vision.

It is often said that the English Reformation created a kind of via media, avoiding the confessional wars of continental Europe. It is true that the Elizabethan theologian, Richard Hooker, forged a system which appealed to scripture, reason and tradition — and, like a three-legged stool, the edifice only stands up if all three legs are present. His contribution to the Elizabethan settlement of religion in the late sixteenth century was undoubtedly important, and Anglicanism has, as a result, a reputation of being ‘reasonable.’

In reality, that Elizabeth Settlement also sowed the seeds of exclusion, which, at least in part, led to the civil war of the seventeenth century, and saw the execution of the Archbishop of Canterbury and the King, and proscription of the Book of Common Prayer. When the Crown was restored in 1660, and the Church of England in 1662, the Church’s settlement this time relied on the exclusion of all those who could not accept either the Book of Common Prayer or the episcopate. Thus, a long and honorable tradition of dissenters emerged.

|

|

Michael Curry, the Presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church USA.

|

Many would say that Anglicanism has been constantly reformed. It both produced and wrestled with the learning of the Enlightenment in the eighteenth century; developed high church and evangelical revivals, as well as a new turn to issues of social justice, in the nineteenth century; saw the ‘independence’ of many churches around the globe in the twentieth century, and simultaneously created a familial network, known as the Anglican Communion, of which the Episcopal Church in the USA is a member.

What has emerged over nearly five centuries, with enduring popularity, is a sense of common prayer and ritual. When Anglicanism has been at its best, it has constantly attracted people to ponder the glory and love of God through the beauty of liturgy, the mystical tradition of prayer, thoughtful and intelligent preaching, music, literature, and art.

Note: See the volume in Princeton University Press's series called "biographies of books," by Alan Jacobs, The Book of Common Prayer, A Biography (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013).

Image credits: (1) Wikipedia.org; (2) Wikipedia.org; and (3) Wikipedia.org.