Philip of Caesarea

By Dan Clendenin

For Sunday May 3, 2015

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Acts 8:26–40

Psalm 22:25–31

1 John 4:7–21

John 15:1–8

In February of 2005, I took a ten-day trip to Ethiopia with a group from my church. That now feels like a long time ago — ten years. But I still cherish several powerful memories.

I'll never forget the firewood girls. Barefoot and bent over at the waist, they carried seventy-five pound bundles of eucalyptus saplings, seven feet wide, down the mountain to the center of Addis Ababa ten miles away, all for a few pennies. The women firewood carriers are such a common sight in Addis that you can read about them in the Lonely Planet guidebook.

Then there's the food, in particular Ethiopia's national dish called injera — a huge circle of spongy flat bread that's made from a very pungent sourdough. When we got home, I was so happy to discover a local Ethiopian restaurant with real injera!

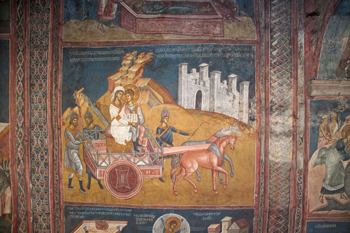

|

Philip teaches the Ethiopian eunuch, Decani Monastery, Kosovo, 14th century. |

We also went to the famous churches in the desert village of Lalibela, about 300 miles north of Addis Ababa. Lalibela is home to eleven underground "cave churches" from the 13th century that were carved out of solid rock. They include sophisticated drainage systems, catacombs, and hermit caves. Their roofs are at ground level. These churches are still places of worship, a destination for pilgrims, and also a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The rock-hewn churches of Lalibela, and even older ones in Tigray from the sixth or seventh century, witness to Ethiopia's ancient Christian tradition. Ethiopia was the first nation to declare Christianity its state religion in 330 (Armenia makes the same claim). Ethiopian artists produced the oldest known illuminated gospel anywhere, and the oldest Ethiopian manuscript of any type — the Garima Gospels from c. 500.

This rich tradition began with the story in Acts 8 about the encounter between the Ethiopian eunuch and Philip the evangelist. The geographical boundaries of Ethiopia then and now are different, but that hardly matters. When that unnamed, newly baptized believer returned home, he took with him what Luke calls "the good news about Jesus." It's a fascinating example of how far and how fast that good news spread — from Jerusalem some 3,000 miles south into sub-Saharan Africa.

There are two Philips in the New Testament, not to be confused. Philip from Bethsaida in Galilee is listed as one of the twelve apostles by all three synoptic writers. This Philip makes several appearances in the gospels, especially in John, and then disappears from the story.

Then there's Philip the Evangelist, as tradition now calls him, from the coastal city of Caesarea Maritima. He makes three appearances in the Biblical narrative, all in Luke's book of Acts.

It's telling that one of the first stories about the early church describes "the daily distribution of food" to widows. Care for the poor was a distinctive sign of the first believers. But we shouldn't romanticize.

Human nature being what it is, Luke also writes that some widows complained that they weren't getting their fair share of food. That was bad enough, but there was also an ethnic-linguistic twist to their argument — the Hellenistic Jews made their complaint against the Hebraic Jews.

|

Philip baptizes the Ethiopian eunuch, Decani Monastery, Kosovo, 14th century. |

To solve this problem, the leaders asked the community to choose some people who were "known to be full of the Spirit and wisdom." Thus did "The Twelve," as Luke calls them, commission "The Seven." Philip was one of the seven believers who was commissioned to solve a nasty dispute. He must have been a fair-minded, no-nonsense sort of person.

Churches have lived with the logic of this decision ever since. In order not to neglect the so-called spiritual responsibilities of "prayer and the ministry of the word," the Twelve appointed the Seven to specialize in the more practical matters of food distribution. And thus our contemporary division of church ministry into the priestly-pastoral and the diaconal-practical.

Philip's next appearance, in Acts 8, indicates how fluid the boundaries of ministry were back then, and why we shouldn't be dogmatic about gifts, titles and functions. Philip the deacon now does the work of a pastor.

When a "great persecution broke out against the church in Jerusalem," the believers "scattered throughout Judea and Samaria." Philip was one of those who fled for the tall grass. This logistics trouble shooter now preaches, performs miracles, and baptizes converts in Samaria, earning the moniker "evangelist" — a word used here and only two other times in the New Testament.

After an encounter with a sorcerer named Simon, and prompted by the Spirit, Philip hit "the desert road" to the south. On his way, he met an Ethiopian eunuch who was a finance minister for the Queen of Ethiopia. This man, a white collar sexual minority from the highest echelon of government, was a long way from home.

Philip "told him the good news about Jesus," and then baptized him. When the Ethiopian parted company with Philip, he "went on his way rejoicing." Once home in ancient Ethiopia, this newly baptized believer sewed the seeds of what grew into one of our oldest and richest Christian traditions.

Once again, "the Spirit took Philip away." Luke says that he "preached the gospel in all the towns" until he got back to his own house in his own town of Caesarea, about 60 miles from Jerusalem.

Then what happened? Nothing much. He disappears from Luke's narrative. Philip seems to have settled down into domestic obscurity.

Years later, he reappears in Acts 21, where Luke reintroduces him as "Philip the evangelist, who was one of the Seven." His house is big enough for his family of six to host Luke, Paul, and their traveling companions for an extended stay. Unlike many early believers who sold their lands and fields, Philip remained a property owner.

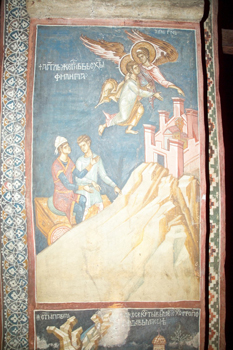

|

The Spirit snatches Philip away, Decani Monastery, Kosovo, 14th century. |

Luke also says that Philip had "four unmarried daughters who had the gift of prophecy." Philip encouraged the ministerial gifts of these women — prophecy, like other women who are called "prophets" in the Bible: Miriam and Deborah, Huldah and Anna, and even Isaiah's wife.

Philip then disappears from the biblical story for good — but not from Christian tradition, where his legacy lived on.

Philip was esteemed by his community. He was always open to the Spirit. He did whatever needed to be done. He lived the good news of Jesus by word and by deed — solving problems like food distribution, preaching and baptizing, and hosting travelers in his home. He nurtured his daughters's gifts. And when the time came, he was just as happy to pull down the flag and rest at home.

He reminds me of one more experience that I had in Addis Ababa. One day we visited the Sisters of Mercy "Home for the Destitute and Dying." It was a day of oppressive heat. The place was horribly overcrowded with people of extreme and complex needs, both physical and spiritual. It was easy to feel depressed. For many visitors, it's just overwhelming.

Then we met our host, Sister Ignacia of Slovakia. She was a prophetic woman who was powerful in word and deed. Sister Ignacia radiated equanimity as she ministered to screaming kids, teenage mothers with newborn babies, the severely retarded, and adults dying of AIDS. At their orphanage, 400 HIV-positive children experienced the love of God.

She welcomed us with genuine kindness — yet another tour group of gawkers, truth be told. And as we stood in a circle, she led us in the Lord's Prayer.

Prophet, priest, problem solver, minister to the poor, and host. I was awed by Sister Ignacia's palpable sense of grace, strength, and joy. Just being in her presence made me feel good, despite all the chaos. Like Philip, she represented all that's good about the good news of Jesus.

Image credits: (1) BLAGO_Fund, Inc.; (2) BLAGO Fund, Inc.; and (3) BLAGO Fund, Inc..