From Ritual Holiness to Human Compassion:

Jesus and the Politics of Purity

For Sunday August 30, 2009

Lectionary Readings

(Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Song of Solomon 2:8–13 or Deuteronomy 4:1–2, 6–9

Psalm 45:1–2, 6–9 or Psalm 15

James 1:17–27

Mark 7:1–8, 14–15, 21–23

At my daughter's soccer team lunch, Hannah gently reminded her daughter to remove the cheese from her Subway sandwich. "It's still not kosher," she laughed, "but at least it's a little better." I admired Hannah's care to follow Jewish dietary laws to "keep kosher" by eating only what is "fit" or "clean" (from the Hebrew word kasher). Following such purity laws (halakha) as a way to express your relationship with God might appear trivial, but in Mark's gospel we see how ritual purity and holiness codes formed the context of the mission and message of Jesus.

The dietary restrictions that Hannah observed comprise only a small part of a comprehensive and complex holiness code that regulated personal and community life for the Hebrew people 3,500 years ago. By one count there are 613 mizvot or "commandments" in the five books of Moses (the Torah). The Levitical purity laws regulated nearly every aspect of being human—birth, death, sex, gender, health, economics, jurisprudence, social relations, hygiene, marriage, behavior, and certainly ethnicity (Gentiles were automatically considered impure).

|

Jesus heals the woman with a flow of blood. |

The purity laws of Leviticus chapters 11–26 specify in minute detail clean and unclean foods, purity rituals after childbirth or a menstrual cycle, regulations for skin infections and contaminated clothing or furniture, prohibitions against contact with a human corpse or dead animal, instructions about nocturnal emissions, laws regarding bodily discharges, agricultural guidelines about planting seeds and mating animals, and decrees about lawful sexual relationships, keeping the sabbath, forsaking idols, and even tattoos.

Why so many rules? Some of these purity laws encoded simple common sense or moral ideals that we still follow today, like prohibitions against incest. Others regulated hygiene and sanitation. Still others symbolized Israel's unique identity that differentiated its people from pagan nations. Ultimately, though, the purity laws and holiness code ritualized an exhortation from Yahweh: "Be holy because I, the Lord your God, am holy" (Leviticus 19:2, NIV). When the Psalmist for this week asks, "Lord, who may dwell in your sanctuary?" the "proper" response is that only people who are ritually clean may approach a holy God (Psalm 15:1). At the center of the purity system, both literally and symbolically, stood the Temple, where one performed rites of purification.

Scholars debate how much or how little ordinary first-century Jews maintained ritual purity, but the Pharisees about whom we read so much in the gospels certainly did. Throughout the gospels they criticized Jesus because of his flagrant disregard for ritual purity. Jesus the Jew touched a leper (Mark 1:41), his disciples did not fast (Mark 2:18f), he ignored sabbath laws (2:23f), he touched a woman with a discharge and handled a corpse (5:21–42), and healed two Gentiles (Mark 7:24f).

In the gospel story this week, perhaps the most important of all the "purity" texts, Mark recounts a clash between Jesus and the Pharisees about food purity. Why, the Pharisees complained, did Jesus's disciples eat with "unclean" hands? Mark includes two parenthetical explanations to his Gentile readers who otherwise might have been clueless: "The Pharisees and all the Jews do not eat unless they give their hands a ceremonial washing, holding to the tradition of the elders. When they come from the marketplace they do not eat unless they wash. And they observe many other traditions, such as the washing of cups, pitchers and kettles" (Mark 7:3–4).

Then, in an aside that we might find trivial but his readers would have found shocking, Mark writes that "Jesus thus declared all foods 'clean'" (Mark 7:19). Nor should we miss the central accusation in this clash. The Pharisees considered Jesus and his followers as ritually unclean sinners who flaunted God's clear laws. In a sense they were right.

|

Jesus heals a paralytic. |

Given our human propensity for justifying ourselves and for scape-goating others, the purity laws lent themselves to a spiritual stratification or hierarchy between the ritually "clean" who considered themselves to be close to God, and the "unclean" who were shunned as impure sinners who were far from God. Instead of expressing the holiness of God, ritual purity became a means of excluding people considered dirty, polluted, or contaminated. In word and in deed Jesus ignored, disregarded and actively demolished these distinctions of ritual purity as a measure of spiritual status.

In Marcus Borg's view, Jesus turned the purity system with its "sharp social boundaries" on its head. In its place he substituted a radically alternate social vision. The new community that Jesus announced would be characterized by interior compassion for everyone, not external compliance to a purity code, by egalitarian inclusivity rather than by hierarchical exclusivity, and by inward transformation rather than outward ritual. In place of "be holy, for I am holy" (Leviticus 19:2), says Borg, Jesus deliberately substituted the call to "be merciful, just as your Father is merciful" (Luke 6:36, my emphasis).

"No outcasts," writes Garry Wills in What Jesus Meant, "were cast out far enough in Jesus' world to make him shun them — not Roman collaborators, not lepers, not prostitutes, not the crazed, not the possessed. Are there people now who could possibly be outside his encompassing love?"

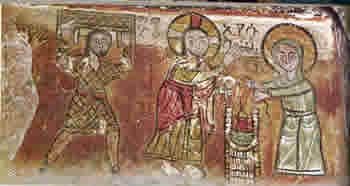

|

Jesus, the paralytic and the Samaritan woman at the well, 13th-century Ethiopia. |

I've found it humbling to ask what "outcasts" do I sanctimoniously spurn as impure, unclean, dirty, contaminated, and, in my mind, far from God. The mentally ill, people who have married three or four times, wealthy executives, welfare recipients, people who hold conservative political opinions, or maybe people with AIDS? How have I distorted the self-sacrificing, egalitarian love of God into self-serving, exclusionary elitism? What boundaries do I wrongly build or might I bravely shatter? I pray to experience what Borg calls a "community shaped not by the ethos and politics of purity, but by the ethos and politics of compassion."

For further reflection:

* Consider: when God hates all the same people you hate, you can be sure that you've created Him in your own image.

* Who are you tempted to exclude as impure and unclean?

* How do we embrace both holiness and compassion, instead of choosing one or the other?

* What does the hierarchy or stratification of impurity look like in your community?

* Watch the film An Uncommon Kindness (2003) about the Flemish priest Damien de Veuster, who ministered to the abandoned lepers on the Hawaiian island of Molokai.

Image credits: (1) United Theological Seminary; (2) PureChristians.org; and (3) Christopher Haas, Villanova University.