Book Notes

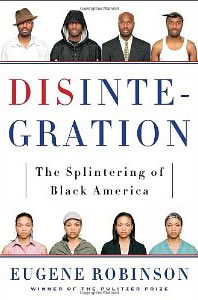

Eugene Robinson, Disintegration: The Splintering of Black America (New York: Doubleday, 2010), 254pp.

Eugene Robinson, Disintegration: The Splintering of Black America (New York: Doubleday, 2010), 254pp.

There are 40 million African Americans in the United States. For decades, perhaps centuries, they have enjoyed and endured a single interpretive narrative of a people with a homogeneous class and culture. Whatever the truth of such a monolithic black America, says Eugene Robinson, it is now long gone and never to return. Instead of a single narrative, black America has experienced a radical "disintegration" that is both hopeful and dispiriting. Indeed, a 2007 Pew poll found that a stunning 37% of blacks agreed with the statement that "blacks today can no longer be thought of as a single race because the black community is so diverse." Robinson proposes that black America has fragmented into four distinct groups that are "increasingly distinct, separated by demography, geography, and psychology. They have different profiles, different mind-sets, different hopes, fears, and dreams."

There's an enormous black middle class that has entered America's mainstream. This is a heroic story that qualifies as nothing less than a "miracle." In 1967, only 25% of black households had a median income of more than $35,000; by 2005, that figure had nearly doubled to 45.3%. The percentage of black households earning more than $75,000 increased from 3.4% to 15.7%. In education, during the same time period, high school graduation rates for blacks increased from 29.5% to 83%, for all intents and purposes, says Robinson, achieving "full parity" with white graduation rates of 87%.

Then there's a black elite that he calls transcendents, like Oprah, Obama, Condi Rice and Colin Powell. There have always been isolated, individual black elites, but now there are enough of them to comprise a "critical mass" that wields influence in every sector of society. Third, there are emergents, made up of two distinct groups — immigrants from Africa and the Caribbean, and then blacks in biracial marriages (which only became legal in all states in 1967). A Pew study found that in 2008, 22% of black males and 9% of black females married "outside their race." Of special interest are the children of emergents, for whom Jim Crow racism is not a bitter, shared experience, but a story learned from history books. Finally, there are the abandoned, symbolized in the events of Katrina and the movie Precious. The abandoned are "profoundly isolated," and because of this have created their own "cultural ecosystems." They need nothing less than an aggressive "domestic Marshall Plan."

Robinson is the perfect person to write this book. He's been a journalist for The Washington Post the last thirty years, a Pulitzer Prize winner, and a Harvard Nieman Fellow. He's lived through the changing social demographics about which he writes. He's read broadly and deeply in history, politics, culture, and social science, but what really drives this book is its frank discussion about unspoken issues. I especially enjoyed Robinson's casual writing style, and the many stories he tells of his own African American experience, whether interviewing the president of the United States or driving through a blighted ghetto. This book, along with Gwen Ifill's The Breakthrough: Politics and Race in the Age of Obama (2009), makes for required reading on the state of race in America.