Book Notes

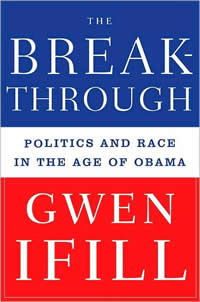

Gwen Ifill, The Breakthrough; Politics and Race in the Age of Obama (New York: Doubleday, 2009), 277pp.

Gwen Ifill, The Breakthrough; Politics and Race in the Age of Obama (New York: Doubleday, 2009), 277pp.

Few public figures are better positioned to write a book on race and politics than Gwen Ifill (b. 1955). As the moderator and managing editor of Washington Week and senior correspondent of The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer, for thirty years the affable and articulate journalist has reported on the sweeping changes in American politics that culminated in what she calls the "Obama effect." As an African-American woman she has also lived this story. The professional and the personal collided with this book, which was released on Inauguration Day (January 20, 2009), when critics charged her with promoting and in turn benefiting from Obama's election.

Obama is only the "leading edge" of radical changes that have redefined the role of blacks in American politics. Today, for example, there are over forty black city mayors. In 2008, 43% of white Americans voted for Obama, an incredible figure when you consider that John Kerry received only 41% in 2004. But there are barriers and boundaries everywhere you turn in this house of mirrors. Obama did his best to run something like a "post-racial" campaign, but Ifill shows that American society remains far from color blind.

Ifill's book is almost entirely anecdotal. She devotes one chapter each to four "case studies" of the new generation of black politicians — Obama, Artur Davis, a congressman from Birmingham, Alabama; Cory Booker, mayor of Newark, New Jersey; and then Deval Patrick, governor of Massachusetts. She then explores four themes — the complex relationship of generation change, in which younger black politicians must relate to their older forbears who carried the torch during the days of the civil rights movement when many of them weren't even born; race and gender — which group is more disadvantaged, and which identity helps or hurts more; legacy politics, in which a younger generation enjoys the advantages and negotiates the disadvantages of a parent politician (eg, Jesse Jackson, Jr.); and then the "politics of identity" that examines how the new generation walks the tightrope of being "too black" for whites and/or "too white" for blacks.

The many stories in Ifill's book show that there's no such thing as a monolithic "black politics." Rather, there are multiple layers, nuances, challenges and opportunities. For the up and coming generation of political super stars, some times race helped them, often it hurt them, but for all of them it always mattered. Not a single person that Ifill interviewed said that race did not matter. My only complaint about this book is that we learn almost nothing about Ifill's own personal experiences as a highly public black woman. Rather, the book reads like a version of her television pieces, scrubbed clean of any private reflections of a deeply personal nature. But since this is only Ifill's first book, I'm hoping for more good things from her.