From Our Archives

Debie Thomas, True Religion (2021); Debie Thomas, Vain Worship (2018).

This Week's Essay

Acts 10:28, "God has shown me that I should not call anyone impure or unclean."

For Sunday September 1, 2024

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Psalm 45:1–2, 6–9 or Psalm 15

James 1:17–27

Mark 7:1–8, 14–15, 21–23

Back when my daughter was playing high school soccer, she had a team lunch at which a Jewish Mom gently reminded her daughter to remove the cheese from her Subway sandwich. "It's still not kosher," she laughed, "but at least it's a little better."

I admired Hannah's care to follow Jewish dietary laws to "keep kosher" by eating only what is "clean" — from the Hebrew word kasher. Following such dietary laws in particular, and the far larger body of laws, customs, and traditions in general (halakha), might seem trivial or superficial to us Gentiles today, but in ancient Israel they were not just important. They were commanded by God as ways for Jews to express their relationship to the Holy.

In Mark's gospel this week, such ritual purity or ceremonial compliance became a flashpoint in the mission and message of Jesus. The story challenges our own religiosity today with its depiction of how easily our sincerity can become sanctimony.

Dietary restrictions were only a small part of a much more comprehensive "holiness code" that regulated every aspect of personal and community life for Jews 3,500 years ago. By one count, there are 631 mizvot or "commandments" in the five books of Moses.

|

|

Jesus heals the woman with a

flow of blood. |

The purity laws of Leviticus 11–26, for example, regulated nearly every aspect of being human — birth, death, sex, gender, health, economics, jurisprudence, social relations, hygiene, marriage, behavior, the calendar, and ethnicity, for Gentiles were automatically considered impure. This holiness code describes clean and unclean foods, rituals after childbirth or a menstrual cycle, regulations for skin infections and contaminated clothing or furniture, prohibitions against contact with a human corpse or dead animal, instructions about nocturnal emissions, laws regarding bodily discharges, agricultural guidelines about planting seeds and mating animals, and decrees about lawful sexual relationships, keeping the sabbath, forsaking idols, and even tattoos. At the center of this purity system, both literally and symbolically, stood the Temple, where one performed rites of purification.

Why so many rules? Some of these purity laws encoded common sense or moral ideals that we still follow today, like prohibitions against incest. Others regulated hygiene and sanitation in a pre-scientific world. Still others symbolized Israel's unique identity that differentiated its holy people from pagan nations.

Ultimately, and at their best, the purity laws ritualized an exhortation from Yahweh in Leviticus 19:2: "Be holy, because I, the Lord your God, am holy." When Psalm 15 for this week asks, "Lord, who may dwell in your sanctuary?" the answer is that only people who are "pure" may approach a holy God.

|

|

Jesus heals a paralytic.

|

We don't know how much ordinary first-century Jews maintained ritual purity, but the Pharisees certainly did. We should not be judgmental about them; they were earnest in the extreme, which is why throughout the gospels they repeatedly criticized Jesus for his flagrant disregard for ritual purity. Jesus the Jew touched a leper, his disciples didn't fast, he ignored sabbath laws, he touched a woman with a discharge, handled a corpse, he healed two Gentiles, and desecrated the Temple.

But somehow — and this is what makes me nervous today — the sincerity of the Pharisees morphed into sanctimony. Their conscientiousness became a type of hypocrisy. Their vigilant efforts at true righteousness became a form of self-righteousness. It's an example of religion itself becoming "the greatest idol of them all," as Richard Holloway puts it in his book A Little History of Religion (Yale, 2016).

There's an interesting connection in the gospel and epistle readings for this week. Jesus warns us of "worshiping in vain" (Mark 7:7). Similarly, James 1:26–27 contrasts religion that is "worthless" with that which is "faultless," faith that is either "true" or "defiled."

In the gospel this week, perhaps the most important of all the "purity" texts, Mark recounts a clash between Jesus and the Pharisees about ceremonial purity. The Pharisees complained that his Jewish disciples ate with "unclean" or "unwashed" hands.

Mark includes two parenthetical explanations to his Gentile readers,who otherwise might have been clueless: "The Pharisees and all the Jews do not eat unless they give their hands a ceremonial washing, holding to the tradition of the elders. When they come from the marketplace they do not eat unless they wash. And they observe many other traditions, such as the washing of cups, pitchers and kettles." To state the obvious, both a person and an object can be pure or impure, clean or unclean.

Then, in an aside that would have shocked his Jewish readers, Mark adds that "Jesus thus declared all foods 'clean.'" What?!

Notice the central accusation in this confrontation. The Pharisees argued that Jesus and his followers were ritually unclean sinners who flaunted God's holy laws. They were "dirty" and "impure." In a sense they were right. But Jesus drew an important distinction. At least seven times he contrasts merely human "traditions" or "rules" with the commands of God. And so, even today, to be "Pharisaical" is to be a hypocrite.

|

|

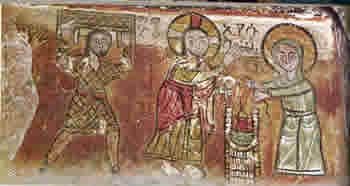

Jesus, the paralytic and the Samaritan woman at the well,

13th-century Ethiopia. |

Given our human propensity to justify ourselves and to scape-goat others, the purity laws lent themselves to a spiritual stratification or hierarchy between the ritually "clean" who considered themselves to be close to God, and the "unclean" who were shunned as impure sinners who were far from God. Instead of legitimate ways to express and honor the holiness of God, ritual purity became a means of excluding people who were considered to be dirty, polluted, unwashed, or contaminated. In word and in deed Jesus ignored, disregarded and actively demolished these distinctions of ritual purity as a measure of spiritual status.

The New Testament scholar Marcus Borg argued that Jesus turned this purity system with its "sharp social boundaries" on its head. In its place he substituted a radically alternate social vision.

The new community that Jesus announced would be characterized by interior compassion for everyone, not external compliance to a purity code, by egalitarian inclusivity rather than by hierarchical exclusivity, and by inward transformation rather than outward ritual. In place of "be holy, for I am holy" (Leviticus 19:2), said Borg, Jesus deliberately substituted the call to "be merciful, just as your Father is merciful" (Luke 6:36).

I love how the historian Garry Wills puts it in his book What Jesus Meant: "No outcasts were cast out far enough in Jesus' world to make him shun them — not Roman collaborators, not lepers, not prostitutes, not the crazed, not the possessed. Are there people now who could possibly be outside his encompassing love?" The answer is no.

I've found it humbling to ask what "outcasts" do I sanctimoniously spurn as impure, unclean, dirty, contaminated, and far from God. How have I distorted the egalitarian love of God into self-serving, exclusionary elitism? What boundaries do I wrongly build or might I bravely shatter? I pray to experience what Borg calls a "community shaped not by the ethos and politics of purity, but by the ethos and politics of compassion."

When I was in grad school I discovered a prayer by Kierkegaard that my wife printed in calligraphy for me. For many years it hung in my office.

Kierkegaard's prayer warns me of self-deception (James), and of confusing the "rules made by men" with "the commands of God" (Jesus).

Herr! gieb Uns blöde Augen

für Dinge, die nichts taugen

und Augen voller Klarheit

in alle Deine Wahreit.Lord! Give us weak eyes

for things that do not matter

and eyes full of clarity

in all your truth.

Weekly Prayer

Thomas à Kempis (1380-1471)

Grant me, O Lord, to know what I ought to know,

To love what I ought to love,

To praise what delights thee most,

To value what is precious in thy sight,

To hate what is offensive to thee.

Do not suffer me to judge according to the sight of my eyes,

Nor to pass sentence according to the hearing of the ears of ignorant men;

But to discern with a true judgment between things visible and spiritual,

And above all, always to inquire what is the good pleasure of thy will.Thomas Hammerken was born in Kempen, Germany and distinguished himself as a priest, monk, and writer. His chief contribution is his manual of Christian discipleship entitled The Imitation of Christ.

Dan Clendenin: dan@journeywithjesus.net

Image credits: (1) United Theological Seminary; (2) PureChristians.org; and (3) Villanova University.