From Our Archives

Michael Fitzpatrick, What Cannot Be Seen (2021); Debie Thomas, A House Divided (2018); and Dan Clendenin, Don't Lose Heart (2015).

For Sunday June 9, 2024

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Psalm 138 or 130

2 Corinthians 4:13–5:1

Mark 3:20–35

This Week's Essay

John 10:20, "He is demon-possessed and raving mad."

In my essay last week I considered the anger of Jesus in Mark 1:41 and 3:5 as a warning about "the dangerous illusion of a manageable deity." As the historian Garry Wills writes in his book What Jesus Meant, "what Jesus signified is always more challenging than we expect, more outrageous, more egregious." When we discover the early historical Jesus behind the so-called later Christ of faith, he becomes more rather than less mysterious to us. And so Mary Gordon calls Jesus "the irresistible incomprehensible."

The gospel for this week is another story about the outrageous, the egregious and the mysterious Jesus — not an angry Jesus, but a crazy Jesus. Just a few verses after Jesus "looked at them in anger" (3:5), he is accused of being demon-possessed, out of his mind, raving mad, beside himself, or of having lost his senses (3:20).

This accusation included a failed attempt at a family intervention: "His family went to take charge of him, for they said, 'He is out of his mind.'" When the crowd alerted Jesus that "your mother and brothers are looking for you," he brusquely dismissed his nuclear family. Who was his family? Anyone who does the will of God. John's gospel tells us that even his brothers did not believe in him.

Was Jesus mad? A lunatic? Certifiably crazy? Many interpreters have tried to reconstruct the mental health of Jesus 2,000 years after the fact, like the four-volume (!) study by the French physician Charles Binet-Sanglé (1868–1941) called La Folie de Jésus (The Madness of Jesus). These retrospective diagnoses draw predictably different conclusions — that Jesus was bipolar, a megalomaniac, a paranoid schizophrenic, a utopian fanatic, an epileptic, and so on. These efforts are obviously anachronistic, and a fruitless endeavor, but they do have the advantage of taking Mark's account seriously.

Other interpreters rebut the idea that Jesus was mentally ill. They assure us that Jesus was perfectly normal, and not a mad man. This view avoids psychological speculation, but it tends toward a safely innocuous Jesus, a meek and mild Jesus who was little more than a do-gooder. He was a Nice Guy, just like we learned from the flannel graphs in Sunday school. This interpretation risks sanitizing Mark's disturbing story — that family, friends, enemies, and authorities were deeply alarmed by the words and deeds of Jesus.

|

|

Luttrell Psalter, England c. 1325–1340 (British Library, Add 42130, fol. 80r)

|

I can easily imagine feeling deeply apprehensive in the presence of Jesus. Just reflect for a moment on the hysteria that Mark describes in the first couple pages of his gospel. "And again a crowd gathered, so that Jesus and his disciples were not even able to eat." Jesus "could no longer enter a town openly" because of the crush of the crowds. People were "amazed at his authority." They wondered aloud, "Who is this? What is this?" At one house "the whole town gathered at the door." News and rumors about Jesus "spread quickly over the whole region."

Instead of psychoanalyzing Jesus, I keep wondering why Mark begins his gospel with such unflattering accounts of Jesus as angry, mad, and even demon-possessed. Why was he such a threat to his family, the religious authorities, and the government? Why are we barely five pages into Mark's story when "they began to plot how they might kill Jesus?" Why do the villagers of Nazareth try to murder him by pushing him off a cliff? Why did the Roman Empire even take any notice of Jesus? How and why did he threaten its political power? Why did Rome execute this village rabbi in a faraway province as a political criminal?

In fact, I think we can connect the anger of Jesus last week (1:41 and 3:5) with the charges of madness this week (3:20). We just need to flip the script. It is the world that has gone mad, not Jesus, and he is rightly angered and aggrieved at this — the religious sanctimony, economic exploitation, political oppression, social exclusion, and the like. And when Jesus disrupts this cultural status quo, he is scapegoated as insane.

The accusations of madness and demon-possession remind me of a famous "saying" by the desert dweller St. Anthony the Great (251–356). He was one of the first believers to flee the madness of the cities for the solitude of the desert. No one would have considered these eccentric monks to have been well-adjusted to a corrupt culture. They were outliers, both literally and figuratively. But they were unapologetic. Abba Anthony said, "A time is coming when men will go mad, and when they see someone who is not mad, they will attack him saying, 'You are mad, you are not like us.'"

Similarly, many people would consider the farmer-poet Wendell Berry (born 1934) to be both angry and insane. And they would be right. Nor would he object to the charges. Berry was born to a family that had farmed Kentucky land for five generations. After studies and travels took him to the University of Kentucky, Stanford, France, Italy, and the Bronx, in 1965 he bought his own farm near his birth place.

He's been tilling the earth and upsetting the status quo ever since. Over fifty books of poetry, novels, essays, and short stories have earned him numerous awards as one of the leading truth-tellers of our day. The "dominant theme of our time," he says, is the violence done against human life and the land.

|

|

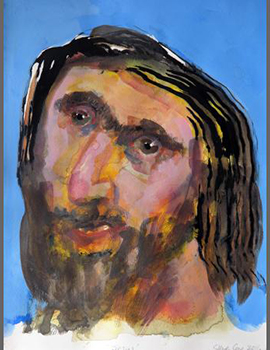

"Insane Jesus" by Steve Cox.

|

Ever since the Industrial Revolution we have had to face the "fundamental incompatibility between industrial systems and natural systems, machines and creatures." He invokes the Amish as "the only communities that are successful by every appropriate standard." He romanticizes the Jeffersonian ideal of small landholders, logging with horses instead of mechanical skidders.

Berry has a series of poems about the Mad Farmer. In 16 poems from 1970 to 2013, the Mad Farmer expresses his grief and anger at the madness of contemporary culture — late stage techno-capitalism, violence to the land, the destruction of our communities. He proposes a counter-cultural vision of a more sane way to live. These poems are manifestos or even ravings by the angry farmer. By the normal canons of culture, the Mad Farmer is crazy, but also unrepentant. Says the Mad Farmer, "To be sane in a mad time / is bad for the brain, worse / for the heart. The world / is a holy vision, had we clarity / to see it — a clarity that men / depend on men to make."

Weekly Prayer

Wendell Berry (born 1934)

Manifesto: The Mad Farmer Liberation Front

Love the quick profit, the annual raise,

vacation with pay. Want more

of everything ready-made. Be afraid

to know your neighbors and to die.And you will have a window in your head.

Not even your future will be a mystery

any more. Your mind will be punched in a card

and shut away in a little drawer. When they want you to buy something

they will call you. When they want you

to die for profit they will let you know.

So, friends, every day do something

that won't compute. Love the Lord.

Love the world. Work for nothing.

Take all that you have and be poor.

Love someone who does not deserve it. Denounce the government and embrace

the flag. Hope to live in that free

republic for which it stands.

Give your approval to all you cannot

understand. Praise ignorance, for what man

has not encountered he has not destroyed. Ask the questions that have no answers.

Invest in the millenium. Plant sequoias.

Say that your main crop is the forest

that you did not plant,

that you will not live to harvest. Say that the leaves are harvested

when they have rotted into the mold.

Call that profit. Prophesy such returns.

Put your faith in the two inches of humus

that will build under the trees

every thousand years. Listen to carrion — put your ear

close, and hear the faint chattering

of the songs that are to come.

Expect the end of the world. Laugh.

Laughter is immeasurable. Be joyful

though you have considered all the facts.

So long as women do not go cheap

for power, please women more than men. Ask yourself: Will this satisfy

a woman satisfied to bear a child?

Will this disturb the sleep

of a woman near to giving birth? Go with your love to the fields.

Lie down in the shade. Rest your head

in her lap. Swear allegiance

to what is nighest your thoughts. As soon as the generals and the politicos

can predict the motions of your mind,

lose it. Leave it as a sign

to mark the false trail, the way

you didn't go. Be like the fox

who makes more tracks than necessary,

some in the wrong direction.

Practice resurrection.

Dan Clendenin: dan@journeywithjesus.net

Image credits: (1) RE|KNEW; and (2) William Mora Galleries.