From Our Archives

Debie Thomas, Don't You Care? (2021); Debie Thomas, Crossing to the Other Side (2018) ; and Debie Thomas, Listening for the Questions (2015).

For Sunday June 23, 2024

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Psalm 9:9-20

2 Corinthians 6:1-13

Mark 4:35-41

This Week's Essay

2 Corinthians 6: 11, "Our heart is opened wide."

It's been said that we want our heroes without blemishes and our villains without redemption. Consider, for example, the bitter rhetoric that justifies the Israeli-Palestinian violence. From such a perspective, there's a binary world of black and white, friends and enemies, the godless and the godly, the innocent and the guilty. In this worldview there is no room for gray. This is the sort of world that's described in two of the readings for this week.

Those of us who went to Sunday School remember flannel graph stories about David and Goliath in 1 Samuel 17. David was the youngest of Jesse's eight sons, relegated to errand boy status, while his older brothers battled the Philistines as manly warriors. Twice the writer describes David as "only a boy." He was "ruddy and handsome." When his brothers berated him, he responded plaintively, "Can't I even speak?" Saul's armor was so big on him that he couldn't move. Then there was his famous slingshot that he wielded — whap! — to slay the nine-foot Goliath who had "defied the armies of the living God." The moral of this Sunday School version was that God uses insignificant people and unlikely means to accomplish improbable feats.

But this sanitized version omits a horrifying detail. David "took hold of the Philistine's sword and drew it from the scabbard. After he killed him, he cut off his head with the sword" (17:51). David then displayed Goliath's head in Jerusalem, brandished it before King Saul, and kept his sword in his tent as a sort of totem. By decapitating Goliath, David wanted to "show the whole world that there is a God in Israel. All those gathered here will know that it is not by the sword or spear that the Lord saves; for the battle is the Lord's, and he will give all of you into our hands" (17:46–47).

David's God will have you beheaded. The purpose of decapitation is to humiliate, traumatize, and terrorize your enemy. It is also what Daniel Benjamin and Steven Simon call a "public sacrament," a "way of making the violence holy." It is "an act redolent with the sense of sacrifice and the literal execution of God's law, which to the jihadist means death for infidels and apostates." Decapitation epitomizes the black and white world with its bold line between good and evil, with God most certainly on your side of the line.

|

|

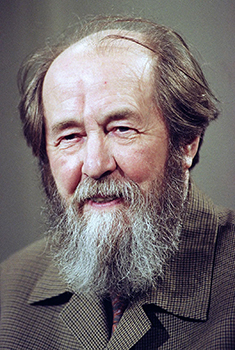

Alexander Solzhenitsyn (1918-2008).

|

David the warrior is also David the poet of Psalm 9 for this week. The experts might quibble, but I would call Psalm 9 an imprecatory psalm. David calls down curses, judgment and calamity on his evil enemies. He hopes that they perish and are destroyed, and that God will "blot out their name forever and ever." He wishes them "endless ruin." He longs for their cities to be destroyed, and the very memory of them to vanish. He reminds his enemies that "he who avenges blood remembers." David concludes his psalm, "Strike them with terror, O Lord!

As I grappled with these two terrifying texts this week, I thought of the words of Jesus: "You have heard that it was said, 'Love your neighbor and hate your enemy.' But I tell you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, that you may be children of your father in heaven." These ancient historical descriptions need not be read as contemporary moral prescriptions. I also thought of two inspirational stories that urge us to move beyond the black and white world of divine vengeance for my enemies.

If anyone might justify divine judgment for unjust persecution, the Soviet dissident and Nobel laureate Alexander Solzhenitsyn (1918–2008) would be a good candidate. In 1945 he was sentenced to ten years of imprisonment and internal exile for criticizing Stalin in a private letter. The publication of his Gulag Archipelago in 1973 outraged the Soviet government for its exposure of the Soviet penal system. With 30 million copies sold in 35 languages, Time magazine called it the most important book of the 20th century. Solzhenitsyn was stripped of his citizenship, and banished to twenty years of exile in Europe and Vermont.

But imprisonment and exile didn't embitter Solzhenitsyn. He even says that he was thankful for prison, because it gave him a deep insight into human nature. Instead of a binary world of black and white, he famously described what he learned: "If only it were so simple! If only it were true that there exist evil people insidiously committing evil deeds, whom it is necessary simply to separate out and destroy… When I lay there on rotting prison straw... it was disclosed to me that the line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either — but right through every human heart — and through all human hearts. This line shifts. Inside us, it oscillates with the years. And even within hearts overwhelmed by evil, one small bridgehead of good is retained. And even in the best of all hearts, there remains… an un-uprooted small corner of evil."

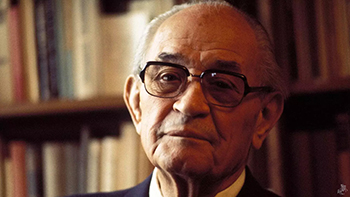

Then there is the German Lutheran pastor Martin Niemöller (1892–1984). Matthew Hockenos wrote what he calls a "revisionist" biography of Niemöller precisely to remind us that even our greatest heroes are imperfect. The title of his book, Then They Came for Me; Martin Niemöller, The Pastor Who Defied the Nazis (2018), comes from Niemöller's famous poetic confession, the exact origins of which remain a mystery:

First they came for the Communists, and I did not speak out – Because I was not a Communist.

Then they came for the Trade Unionists, and I did not speak out – Because I was not a Trade Unionist.

Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out – Because I was not a Jew.

Then they came for me – and there was no one left to speak for me.

As Hockenos shows, by his own admission, and for a long time, resistance is exactly what Niemöller did not do. Whereas Solzhenitsyn was given an insight about human nature, Niemöller was badly mistaken about God's nature.

Martin Niemöller was both deeply Christian and fervently nationalist. For him there was a connection between throne and altar, patriotism and spirituality. Serving in the navy for nearly ten years as a submarine commander in World War I fulfilled a childhood dream. After Germany's humiliating defeat, he detested the liberal, democratic Weimar Republic. He voted for Hitler and the Nazi Party twice (1924, 1933). He longed for the good old days of the traditional monarchy. Even when he was imprisoned he volunteered to rejoin the German military in World War II. And even though he spent eight years in prison as Hitler's "personal prisoner," that was only because he objected to Hitler's interference in the Lutheran church; he had little to say about his treatment of Jews, or his economic, domestic, or foreign policies.

|

|

Martin Niemöller (1892-1984).

|

Only around 1933 to 1934 did Niemöller begin to repudiate his ultranationalist and antisemitic views, and articulate his personal responsibility for not resisting more, along with the collective guilt of the entire nation for the Holocaust. And so two times in his biography Hockenos tells the story of how in 1945 Niemöller took his beloved wife Else back to Dachau to show her the cell where he had been imprisoned. Standing in front of the crematorium, they saw a simple plaque that read, "Here in the years 1933 to 1945, 238,756 people were cremated."

Niemöller later recalled that when he read the plaque, "a cold shudder ran down my spine." It wasn't just the number of people murdered that haunted him, it was the dates. Dachau opened in 1933. At that time Niemöller was a free man and a prominent pastor. "My alibi accounted for the years 1937 to 1945" [in prison], he said, "but God was not asking me where I had been from 1937 to 1945 but from 1933 to 1945… and for those [earlier years] I did not have an answer."

And yet Niemöller did change, even radically so, compared to his earlier self. In his later years the militant German nationalist became an ardent global pacifist. He traveled the world as an ecumenical ambassador. His message by that time was threefold: "the futility of war, the importance of church engagement in public affairs, and the need to build a worldwide Christian brotherhood."

"It look me a long time to learn," said Niemöller, "that God is not the enemy of my enemies. He's not even the enemy of his own enemies."

Weekly Prayer

Saint Francis of Assisi (1182–1226)

The Peace Prayer of Saint Francis

Lord, make me an instrument of your peace.

Where there is hatred, let me sow love;

Where there is error, truth;

Where there is injury, pardon;

Where there is doubt, faith;

Where there is despair, hope;

Where there is darkness, light;

And where there is sadness, joy.

O Divine Master, grant that I may not so much seek

To be consoled as to console;

To be understood as to understand;

To be loved as to love.

For it is in giving that we receive;

It is in pardoning that we are pardoned;

It is in self-forgetting that we find;

And it is in dying to ourselves that we are born to eternal life.

Amen.We do not know the author of this classic prayer, and it was not until the 1920s that it was even ascribed to Saint Francis. By one account the prayer was found in 1915 in Normandy, written on the back of a card of Saint Francis. But it certainly emulates his longing to be an instrument of peace, reconciliation and redemption in our fallen world.

Dan Clendenin: dan@journeywithjesus.net

Image credits: (1) Britannica and (2) Die Tagespost.