For Sunday December 5, 2021

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Baruch 5:1-9 or Malachi 3:1-4

Luke 1:68-79

Phillipians 1:3-11

Luke 3:1-6

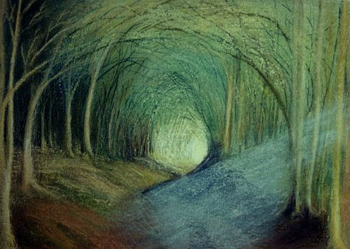

Advent is a good time to remember that the Bible we read and reverence is a wilderness text. A text borne of trauma, displacement, and loss. The ancient writers who penned sacred scripture — and the vast majority of characters who populate its pages — were not, by and large, history’s winners. They were the persecuted. The dislocated. The enslaved. The desperate. They lived through periods of famine, war, plague, and natural disaster. They suffered starvation, violence, barrenness, captivity, exile, colonization, and genocide. They were, in countless ways, the wretched of the earth. Brave, lonely voices, crying in the desert.

But what did they cry? They cried their sorrow, of course. In the shadowed valleys of the wilderness, they cried their rage, fear, horror, and pain. But here’s the remarkable thing: they also cried their hope. Their fierce, muscular hope in a God who cares. A God who vindicates. A God who saves. Something about the wilderness experience birthed in them a capacity for profoundly life-changing hope. Salvific hope. Hope beyond hope.

So perhaps it’s fitting that on this second Sunday in Advent, we are invited into the wilderness to listen to just such a voice — a voice of robust hope, crying out the truth of God’s faithfulness in the most bereft and desolate of places.

|

I’ve never seen John the Baptist featured in an Advent calender, but all four Gospels place him front and center in Jesus’s origin story. The baptizer clothed in camel’s hair is the only gateway we have to the swaddling clothes, angel's wings, and fleecy lambs we hold dear each December. As baffling as it may seem, the holy drama of the season depends on John's lone, abrasive voice, crying out in the wilderness.

“In the fifteenth year of the reign of Tiberius,” Luke writes, “when Pontius Pilate was governor of Judea, and Herod was ruler of Galilee, and his brother Philip ruler of the region of Ituraea and Trachonitis, and Lysanias ruler of Abilene, during the high priesthood of Annas and Caiaphas,” John hears God’s word in the wilderness. That’s seven seats of wealth, power, and influence in just one sentence. Seven centers of authority, both political and religious. Seven Very Important People occupying seven Very Important Positions. But God’s word doesn’t come to any of them. The story of the Incarnation begins elsewhere. It begins in obscurity, off the beaten path, appallingly far away from the halls of dominion and might.

Perhaps the first lesson of the wilderness, then, is a lesson about power. Our Gospel this week highlights a startling juxtaposition between those who experience God’s speaking presence and those who don’t. In Luke’s account, emperors, governors, rulers, and high priests — the folks who wield power — don’t hear God, but the outsider from the wilderness does. The word of the Lord comes to John, the one who gives up his hereditary claim to the priesthood, trading its clout and comfort for the privations and humiliations of the desert.

|

What is it about power that deafens us to the Word? Maybe Tiberius, Pilate, Caiaphas, and Herod can’t receive a fresh revelation from God because they presume to hear and speak for God already. After all, they’re in power. Doesn’t that mean that they embody God’s will automatically? If not, well, who cares? They already have pomp, money, military might, and the weight of religious tradition at their disposal. They don’t need God.

But in the wilderness? In the wilderness, there’s no safety net. No Plan B. No fallback option. In the wilderness, life is raw and risky, and our illusions of self-sufficiency fall apart fast. To locate ourselves at the outskirts of power is to confess our vulnerability in the starkest terms. In the wilderness, we have no choice but to wait and watch as if our lives depend on God showing up. Because they do. And it’s into such an environment — an environment so far removed from power as to make power laughable — that the word of God comes.

But Luke goes on. Not only is the wilderness a place that exposes our need for God. It’s a place that calls us to repentance. “John went into all the region around the Jordan,” Luke tells us, “proclaiming a baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of sins.” Elsewhere in the Gospels, we read that crowds streamed into the wilderness to heed John’s call. In other words, they left the lives they knew best, and ventured into the unknown to save their hearts through repentance. Something about the wilderness brought people to their knees. Something about the possibility of confession and absolution stirred and compelled them to turn their staid lives, routines, and rituals upside down.

Yes, I know that “sin” and “repentance” are loaded words. I know that we're wary of them, for good reasons. They are words which have been weaponized to frighten and diminish us. They are words that have been deployed in very narrow ways to pit us against each other, politically, economically, and culturally.

|

But here’s the thing: Advent begins with an honest, wilderness-style reckoning with sin. We can’t get to the manger unless we go through John, and John is all about repentance. Is it possible that this might become an occasion for our liberation? Maybe, if we can get past our baggage and follow John out into the wilderness, we’ll find comfort in the fact that we don’t have to pretend to be perfect anymore. We don’t have to deny the truth, which is that we struggle, and stumble, and make mistakes, and mess up. We can face the reality that we are fallible human beings, prone to wander, and incapable of living up to our own ideals. And — most importantly — we can fall with abandon and relief into the forgiving arms of a God who loves us as we are. We can live into the tenacious hope of our Biblical ancestors — the hope of restoration. The hope of abundant and overflowing grace. The hope of salvation.

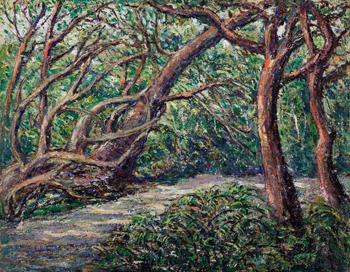

Finally, Luke suggests that the wilderness is a place where we can see the landscape whole, and participate in God’s great work of leveling. Quoting the prophet Isaiah, Luke predicts a day when “every valley shall be filled, and every mountain and hill made low, and the crooked shall be made straight, and the rough ways made smooth.”

|

Unless we’re in the wilderness, it’s hard to see our own privilege, and even harder to imagine giving it up. No one standing on a mountaintop wants the mountain flattened. But when we’re wandering in the wilderness, and immense, barren landscapes stretch out before us in every direction, we’re able to see what privileged locations obscure. Suddenly, we feel the rough places beneath our feet. We experience what it’s like to struggle down twisty, crooked paths. We glimpse arrogance in the mountains and desolation in the valleys, and we begin to dream God’s dream of a wholly reimagined landscape. A landscape where the valleys of death are filled, and the mountains of oppression are flattened. A landscape so smooth and straight, it enables “all flesh” to see the salvation of God.

So. Where are you located during this Advent season? How close are you to power, and how open are you to risking the wilderness to hear a word from God? What might repentance look like for you, here and now? Where is God leveling the ground you stand on, and what will it take for you to participate in that uncomfortable but essential work?

The word of the Lord came to John in the wilderness. May it come to us, too. Like John, may we become hope-filled voices in desolate places, preparing the way of the Lord.

Debie Thomas: debie.thomas1@gmail.com

Image credits: (1) Missale.net; (2) AdventDoor.com; (3) Art Is Hard; and (4) www.1stdibs.com.