For Sunday April 9, 2017

Palm Sunday

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Isaiah 50:4–9a

Psalm 31:9–16

Philippians 2:5–11

Matthew 26:14–27:66 or Matthew 27:11–54

A guest essay by Ron Hansen. Ron's many books include, most recently, The Kid (2016), Exiles (2008) and A Wild Surge of Guilty Passion (2011). Among his many honors are a Guggenheim Foundation grant, an Award in Literature from the American Academy and National Institute of Arts and Letters, two grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, and a three-year fellowship from the Lyndhurst Foundation. He is currently the Gerard Manley Hopkins, S.J. Professor in the Arts and Humanities at Santa Clara University, where he earned an M.A. in Spirituality in 1995.

Some years ago I was a participant in a month-long silent retreat with the Spiritual Exercises of Ignatius Loyola. The format was a so-called first week — for it can be much longer — of developing a sense of God’s presence in the world, our personal sin, and how to orient oneself to God and away from worldly attachments. Some retreatants spend the whole thirty days there.

|

|

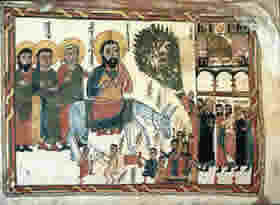

Jesus's Triumphal Entry, Medieval Syriac manuscript.

|

In the second week, retreatants develop a deeper friendship with Jesus, witnessing his preaching, his miracles, his way of being in order to imitate him more closely in our own lives. It was a rather joyful and comfortable place to be, and I could have stayed there much longer as I dreaded the third week and its contemplations on the persecution and execution of Jesus.

But I had a dream one night that I was casually bicycling on a road through the lovely woods with Jesus when we encountered a creek that was in flood. Jesus got off his bike and rolled his robe up over his knees in order to wade across. Looking over his shoulder, he saw that I was unmoving and said, “I have to go over to the other side. I am my death.”

|

|

The Condemnation of Christ and the Denial of Saint Peter, early fifth century, British Museum, London.

|

I recounted that dream to my spiritual director the next morning and he wisely understood it as my own metaphorical interpretation of Palm Sunday and of God’s decisive call for me to finally enter the third week of the exercises that I’d been resisting. But my director was troubled by “I am my death.” What did I think was meant? And it struck me then, as now, that in every Catholic site I have visited in America or internationally the principal image, even the focus in the church, was of a Jesus nailed to a cross and writhing in agony. His dying is ever present. I am my death makes perfect sense on an iconic level.

I seem to recall that in my childhood Palm Sunday and the Passion of the Lord were not joined as two gospel readings on the same day. The Passion read or dramatized from the Gospel of John was for the end of Holy Week. But the humiliation and suffering of the crucifixion are of such significance to Christianity that it was thought too important to somehow miss if one was otherwise obligated on Good Friday.

|

|

Mosaic of Christ before Pilate, Basilica of Saint Apollinare Nuovo, 6th century.

|

And so we have Jesus entering Jerusalem on a donkey via the Mount of Olives in a conscious imitation of the prophecy of Zechariah that God’s anointed one would arrive in that way, and also as a sarcastic comment on the arrogance and panoply of Roman officials entering the city. The triumphant, exultant exclamations of “Hosanna” from the followers of Jesus would of course in five days become jeers of derision with acclamations to go along with the judgments of the Sanhedrin to crucify him. And so our Palm Sunday begins in exhilaration and ends in regret and sadness.

In 2004 I was happily invited to Icon Studios in Los Angeles to view a preliminary cut of The Passion of the Christ with its director Mel Gibson present, along with about thirty representatives of the crew and media. I found it a wrenching, powerful, important film, and commented afterward that at various times in the watching you find yourself either weeping or praying.

| |

|

Cucifixion icon, Sinai, 8th century.

|

Carefully reading the four gospel accounts of the Passion can have the same result. But Holy Saturday, when Jesus lies dead, is given short shrift in our liturgies as it’s generally ignored in the passage from Good Friday to the Easter Vigil.

But on that long Ignatian retreat in Massachusetts, I attempted to contemplate Holy Saturday and felt I’d failed utterly. Although I’d been happy at the Easternpoint retreat house, developed a satisfying and prayerful daily routine, and loved walking along the Atlantic shore near Gloucester, waves bursting against its granite boulders, I found myself contemplating Holy Saturday on my twin bed in my cell, strangely bereft and crying and profoundly depressed, capable only of listening over and over again to Amadeus Mozart’s gorgeous “Ave Verum Corpus,” about the body of Jesus lying in state.

|

|

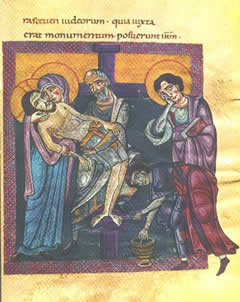

Descent from the Cross, 12th century, parchment, Nonantola (Modena, Italy), Abbey`s Library.

|

It was a day full of loneliness, grief, and gloom that I couldn’t explain. I confessed my failure the next morning to my spiritual director and he seemed shocked that I didn’t recognize what had happened to me, saying, “Don’t ask for a grace and not expect to get it.” I saw then that I’d been privileged to experience what the disciples of Jesus felt on Holy Saturday, their hopes dashed, their faith in ruins, all their former longings haunting them. Without the zest of Palm Sunday, without the grander future they’d anticipated — the grief was not just over the loss of a friend but of their reason for being.

We need to dwell on that and all the inspiring and upsetting events of Holy Week to fully appreciate the victory of Easter.

Image credits: (1) Christopher Haas, Department of History, Villanova University; (2) Museum of Antiquities, University of Saskatchewan; (3) Robert W. Brown, Dept. of History, University of North Carolina Pembroke; (4) Jugoslav Ocokoljić; and (5) Chiesa Cattolico di Torino.