Amy Frykholm is the author of a book on sexuality and Christianity called See Me Naked: Stories of Sexual Exile in American Christianity. She is also an associate editor at Christian Century and holds a Ph.D. in literature from Duke University. She has written widely in essays and books about the relationship between American culture and religion. I came across See Me Naked last year, and resonated immediately with Amy's attempt to integrate faith and sexuality in ways that honor the complexity of both. I recognize so well the world her book describes, and I'm grateful to have this opportunity to explore it further.

Debie: Welcome to JwJ. Thank you for joining us.

Amy: Thanks for having me.

Debie: In your latest book, See Me Naked, you explore a range of topics having to do with spirituality, sexuality, and the body. Through your profiles of nine Christian Protestants grappling with their sexuality and their faith, you delve into subjects like abstinence, sexual abuse, pornography, prostitution, and homosexuality. Tell us about what prompted you to write this book. Did you feel you were entering into a conversation already-in-progress? Breaking a silence? Or something else?

Amy: At the moment that I began the book, which was at least ten years ago, I didn’t feel that the conversation on Protestant Christianity and sexuality was very advanced. The book had a gradual evolution, and I think our cultural conversation has been evolving as well. Purity culture, for example, has lost a lot of its cultural dominance, and I think this is a great development.

More personally, I noticed that I was fairly obsessed in my writing with the relationship between physical bodies and spirituality or religion. Obviously there was something in my own background that I needed to reckon with.

But I didn’t know how to do this, how to tell this story. I decided just to start interviewing people and asking them to tell me the story of the relationship between their religious lives and their sexual experience. It was a story most of the people I interviewed had never told before and that made the stories both raw and inviting.

Debie: "Exile" is a governing metaphor in your work. You describe the men and women in your book as exiles wandering in the wilderness. What is sexual exile? What does this particular wilderness look like for contemporary Christians?

Amy: I used the word “exile” to describe a really personal experience that, in the process of interviewing, I discovered was more universal than I had anticipated. That is, I had a long habit of walling off my sexual experiences from my religious life. They simply existed in two different realms, and I didn’t even imagine bringing them together or imagine that they had any relationship beyond shame and guilt.

One day I was sitting in a diner interviewing a devoutly religious man who had struggled with sexual addiction. Out the window, I saw a newspaper headline about Ted Haggard (the once celebrated pastor of a megachurch in Colorado Springs) whose “secret” sex life had just been exposed, and I realized that I had something in common with both of these men. We all had experienced what I came to call sexual exile — the body out roaming in the wilderness exiled from religious and spiritual ground.

Debie: You argue that sexual exile in America is a problem with specific Protestant roots. Would you say more? What are those roots?

Amy: American Protestants tend to think that religion is a question about belief. Do you believe or not? Belief is then imagined as a kind of cognitive assent to a proposition. For me, this way of orienting oneself religiously leads directly to sexual exile. We have associated this belief proposition with following a set of rules — rules that lead to a holy life. Rules then lead to judgment over whether one has properly followed them or not. And this leads, in my experience, to lacking even the ability to perceive how the body might be interacting with the world — again except through the realm of shame. I equate Protestant understanding of sexuality with how our culture handles dieting. Here’s a program to follow. Notice when you fail and try to do better. We now know that dieting doesn’t lead to weight loss. It just leads to deep confusion and a war between body and mind — not to mention spirit.

|

|

Adam and Eve, contemporary Ethiopia.

|

Debie: I wonder if this is part of a larger problem with American Christianity's relationship to its surrounding culture. Often the relationship is defensive and adversarial.

Amy: This is true. Protestants also have a tendency to see themselves at the margins of American culture — although closer examination would certainly challenge this idea. How do you know if you are a Christian? If you have a special belief and special rules that you follow that separate you from the culture, then you are a Christian. You demonstrate a purity where the “world” is sullied. In practice, Christians don’t actually act all that differently than non-Christians. When I studied the statistics and realized that “belief” had little effect on behavior, I was fascinated. But Christians often use statistics that point this out, not to question the paradigm, but just to shame ourselves and each other with more ferocity.

I thought that the statistics might suggest a profound disconnect between mind and body that needed some interrogation.

Debie: Early in the book, you describe the disconnect as a kind of Christian myth. Specifically, a myth that teaches us that "Christian sex" will protect us from heartache and plant us squarely in God's will.

Amy: Christian sex and so-called secular sex just aren’t that different. Christians have a tendency to project an ideal and then judge themselves according to that ideal. But the ideal has become ever more detached from reality. It fails us in pretty profound ways. I would argue that it drives us away from a central proposition of Christianity: incarnation. In the book, I describe the way that it drives people into the wilderness.

Debie: But exile and wilderness aren't necessarily negative metaphors for you.

Amy: In the Christian tradition, the wilderness is a powerful place where God can often be met, a place of strange and wonderful occurrences.

Debie: You chose to write your book in the form of stories. Why? How might storytelling offer a way through the wilderness? Or even a way through the cultural impasse of "us" versus "them?"

Amy: I noticed pretty quickly that almost all of the literature on this subject was prescriptive. Do this. Don’t do that. I could not write this kind of book. First of all, I do not consider myself any kind of expert on what other people should or shouldn’t do sexually. Secondly, I didn’t find this kind of literature particularly helpful, and it didn’t come anywhere near close to articulating what fascinated me. I remember reading Lauren Winner’s Real Sex when I started writing this book and thinking, “The sex in this book isn’t anywhere near real enough.” So how could we break out of the prescriptive mode?

Stories complicate questions, I think. They offer layers of meaning, moments of choice. Stories allow us to see how a person was shaped by various forces in their environment and how that in turned shaped choices they made. Stories also turn us away from the prescriptive through the very fact that they are multiple. Individual stories can be read in multiple ways and multiple stories complicate individual assumptions.

I also turned to stories because I thought that they might give us what Parker Palmer calls in The Courage to Teach a “third thing” to give our attention to. The subject of sexuality and religion is hampered by so many cultural and social taboos, such poor ground, such fear of vulnerability, that I hoped these stories might provide “third things” — resources for a richer conversation.

Debie: In many ways, I see your book as an attempt at reclamation. You reclaim words we've surrendered to the secular media or the porn industry. Words like pleasure, desire, eroticism, sensuality, intimacy, and attraction. What has the Church lost in shunning these words? What would Christians gain by recapturing them?

Amy: When I wrote that I wanted to reclaim the word “pleasure,” it felt dangerous to me. I don’t know if that was true or not, but it felt true at the time. We are afraid of pleasure. I was afraid of pleasure. Pleasure really gets a bad rap in religious circles, so I was surprised to read recently in Michel de Montaigne (a very devout 15th century writer and “father” of the modern essay) an argument similar to mine. “When pleasure is taken to mean the most profound delight and an exceeding happiness, it is a better companion to virtue than anything else.” My turn to pleasure and desire and attraction was a call to pay attention. The erotic is a call to love, a call of love. If we pay attention to that call, we learn something holy. Even in the confession of sin, we say, “that we may delight in your will.” We learn delight through pleasure.

Debie: I suppose the challenge in re-integrating spirituality and sexuality is that our sexuality is both robust and delicate. Erotic energy is beautiful and life-giving, but it's also dangerous. How do we honor those tensions? How do we balance pleasure with discernment? Creative and healthy sexual formation with sound moral formation?

Amy: I love that phrase “robust and delicate.” I think that’s right. I would suggest that the answer is again in paying attention. We often turn to sexual stimuli — like food or television or alcohol — not to pay attention, but to divert our attention. This is not what I am talking about, and I don’t think it is a particularly promising path for re-integration. Attention would lead us to ask: is this loving? Am I learning to love? Is this particular way of being in the world leading me to love? What is my body aware of in this moment that my mind is closed to?

I would allow more space for failure than our current religious culture allows us. It is a process to learn to love another person or to learn to love ourselves. I was speaking about this book in an undergraduate class at a Christian college once, and a young man asked me if it was OK for a husband and wife to engage in certain sexual practices. I was struck by how accustomed he was to getting prescriptive advice from people like me and how much he wanted that advice. But I couldn’t give it to him. I had to admit that the process of learning to love another human being wasn’t something that could be taught by books — mine or anybody else’s. That’s work you have to do in your own body engaged with the body of another person. And that work is, well, delightful.

|

|

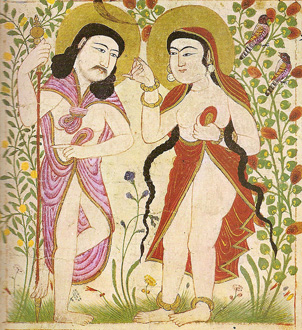

Adam and Eve, 13th century Persia.

|

Debie: Many of the people you interviewed for the book told sexual coming-of-age stories. Specifically, they described what it was like to grow up in Christian churches where sex was only discussed — if it was discussed at all — in the context of rules, rules, rules and shame, shame, shame. What do you think a healthier approach to sexual formation could look like in the Church?

Amy: I would love for us to find another place to begin the conversation other than, “Is it OK to…?”

I researched a story for The Christian Century on a curriculum for sexual formation called “Our Whole Lives.” I loved the complexity of the questions it led young people into. For example, there was a striking lesson on consent, where young people practiced saying “yes” and “no” to various things, and I think everyone in the room was viscerally aware in a new way of how difficult a question like consent is. This was a wonderful introduction to fearless sexual formation, accompanied by a religious community.

Debie: Maybe the first "sexual" word we need to reclaim as Christians is "Incarnation." You've argued that American Protestantism is particularly weak in its imaginative understanding of Incarnation. Which is so ironic, given its centrality to Christian theology. We're squeamish about bodies. Jesus's body. Our bodies. What would it look like to reclaim the body as a vehicle for the holy?

Amy: God may not be too put off by our unwillingness to accept the radical conditions of love. That is — whether we cognitively accept God’s physical grace, it is still being conveyed through our bodies. I love this line from the French critic Hélène Cixous, who I don’t think imagined that it was about Incarnation: “my body knows unheard-of songs.” In the book, I suggested this might be called a sexual ethic of wonder: we meet sexuality with more questions than answers, more space to be changed than fear.

Debie: I wonder if what we fear most about embodiment is vulnerability. Jesus made himself vulnerable in the flesh. But isn't this where spirituality and sexuality meet? Both require openness. Trust. Vulnerability.

Amy: Yes. And again yes. Somebody asked me if I was essentially saying that we just needed to talk about sex more. I don’t think this is it. Sexuality is tender and delicate. It may grow in the dark for good reasons. But when we observe the possibility of the body and sexuality as vehicles of grace, I think we find ourselves more alive in the world. And when we are more alive, we are more open, and when we are more open, more love can flow through us.

Debie: Amy, thank you so much for talking with us. Your work on this subject is courageous and essential, and we're grateful to you for engaging in it.

Amy: Thank you, Debie, for continuing this conversation.

Image credits: (1) Wikipedia.org and (2) Wikipedia.org.