Book Notes

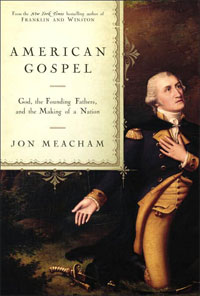

Jon Meacham, American Gospel; God, the Founding Fathers, and the Making of a Nation (New York: Random, 2006), 399pp.

Jon Meacham, American Gospel; God, the Founding Fathers, and the Making of a Nation (New York: Random, 2006), 399pp.

Some atheists and agnostics argue to remove "in God we trust" from our currency. Conservatives on the religious right work for prayer in our public schools. Secularists fear religious zealotry, and believers abhor moral anarchy. In this popular level historical overview of the relationship between church and state, religion and politics, Jon Meacham, the managing editor of Newsweek and a practicing Christian, argues against both extremes. There is, he insists, a well-defined historical common middle ground, what he calls a "sensible center," that best serves the many and varied interests of our country. Meacham writes to help us recover that successful effort of our founding fathers to "assign religion its proper place in civil society." He writes with the hope that we can move beyond discord and division to both reverence and tolerance.

It is "wishful thinking" rather than sound history to imagine that America was founded as a specifically "Christian nation." Meacham does a good job of showing how and why this falsehood propagated by conservative Christians is not true. George Washington, for example, is not known to have taken communion, and one bishop who knew him was confident he was not a believer. Jefferson's scissored-down New Testament is well known. In the realm of what Meacham calls "public religion" the founding fathers thus assiduously avoided any sectarian bias. They strongly protected the right of every citizen to freely exercise "private faith," or no faith at all, as each individual conscience saw fit. Such was the paradox between political liberty and religious faith: "Many, if not most, believed; but none must."

But understood in a broad, generic sense, America is a very religious if not specifically "Christian" nation. On the whole, Meacham thinks the benefits of this legacy have outweighed the costs. Even today it would be silly, and impossible as a practical matter, to deny or try to eradicate this collective cultural consensus that we have inherited. The Declaration of Independence thus argues that rights are God-given and not granted by the state, even though this "God" is deliberately and vaguely defined, and the Constitution never mentions him. Or again, if you look at the image on the back of a dollar bill you see one of our three national mottoes, the "Eye of Providence" above an unfinished pyramid with the phrase, "God has favored our undertakings" (Annuit Coeptis) — taken not from any Biblical literature but from the poet Virgil. In another line of argument, Meacham appeals to the likes of Homer and William James to observe that all human beings are naturally religious, and that to deny this impulse is both wrongheaded and futile. He considers it natural and probably healthy for our country that virtually all presidents and our most important leaders make public if deliberately vague appeals to the Almighty, from Lincoln and FDR to Martin Luther King, Jr.

Meacham makes copious use of quotations from primary resources (documented in 80 pages of end notes). A long appendix provides nine examples of divergent primary documents on the public role of religion in America—for example, a letter from George Washington to a Jewish congregation, a treaty between America and Muslim Tripoli ratified by the Senate in 1797 that declared "the government of the United States is not in any sense founded on the Christian religion," and a letter from the nineteenth-century free thinker Robert Ingersoll that defines the "religion" (his word) of secularism. At times the book is so general that Meacham only skips across the mountain tops. One chapter begins with the Civil War, devotes a few pages to Darwin, and finishes with Wilson. But that's a minor quibble for an otherwise excellent popular treatment of the "shrewd compromise" that our founders made between protecting private faith and insuring public freedom.