Book Notes

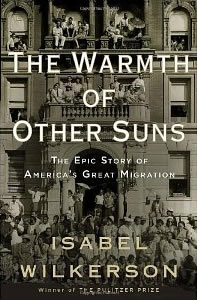

Isabel Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns; The Epic Story of America's Great Migration (New York: Random House, 2010), 622pp.

Isabel Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns; The Epic Story of America's Great Migration (New York: Random House, 2010), 622pp.

Social scientists call it America's "Great Migration," and it explains why when I lived in the suburbs of Detroit I heard distinctly southern accents. Both a cause and an effect that shaped our country, between 1915 and about 1970 six million blacks migrated from the south to the American north and west. Wilkerson calls it the biggest under reported story of the twentieth century. When the migration began, about 90% of blacks lived in the south; sixty years later only 50% of them did. The black population in Chicago swelled from 44,000 to over a million. Detroit's skyrocketed from 1.4 percent to 44 percent.

Wilkerson, who won a Pulitzer Prize in 1994 as the Chicago bureau chief for the New York Times, interviewed 1200 migrants for her book. She humanizes this history by telling the stories of three individual migrants who represent the three main paths that blacks took out of the south — up the Atlantic seaboard to the northeast, up the spine of the country to the cities of the midwest, and then west mainly to California. She even re-enacted these stories by driving from the south to California. Between alternating chapters about these three people, she intersperses straightforward social scientific analysis from history, economics, politics, and culture.

When Ida Mae Brandon Gladney (b. 1913) left her sharecropper's shack and the cotton fields with her husband George in late October of 1937, she had never been outside of Chickasaw County, Mississippi. She died in Chicago in 2004. George Swanson Starling (1918–1998) left the citrus fields of Eustis, Florida on April 14, 1945. He had completed two years of college, a miracle for that time and place, then after a stint in Detroit he settled in Harlem where he spent fifty years with his wife Inez as a rail car baggage handler. Robert Joseph Pershing Foster (1919–1997) was a surgeon from Louisiana who couldn't operate in white hospitals or on white patients, even though he had served in the army and lived in a "parallel universe" of black aristocracy. Once he resettled in California, he became a noted physician to the likes of singer Ray Charles.

Wilkerson does not romanticize these personal journeys. Migrants discovered a new and virulent strain of "hyper-racism" in the north and west that led to all sorts of difficulties and disillusionments in housing, education, health care, and employment. Not only whites (especially European immigrants), but old-time blacks resented the new arrivals. Much of the book, especially her portrayal of life in the south during Jim Crow (lynchings, terror, torture, violence, apartheid), makes for painful reading. We all owe a debt to these brave people who fled what Wilkerson calls a "feudal caste system" and forced America to move beyond two hundred years of racism.