Book Notes

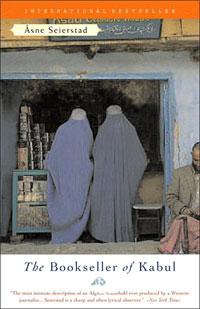

Åsne Seierstad, translated by Ingrid Christopherson, The Bookseller of Kabul (New York: Back Bay Books, 2002, 2004), 288pp.

Åsne Seierstad, translated by Ingrid Christopherson, The Bookseller of Kabul (New York: Back Bay Books, 2002, 2004), 288pp.

In November 2001, after the fall of the Taliban, the Norwegian journalist Åsne Seierstad befriended a bookseller in Kabul who invited her to his home for dinner. Before long they agreed for her to live in Sultan Khan's home for three months in order to write a book about about his family. The Bookseller of Kabul, an international bestseller translated into thirty languages, and the most successful nonfiction book in Norwegian history, chronicles Seierstad's first person narrative about her experiences of Afghan gender roles, education, politics, religion, and culture.

At first Seierstad thought she had met a remarkably liberated Afghan man. Sultan was an ardent bibliophile who loved books and ideas. In a country where three-quarters of the population is illiterate, he had amassed a collection of 10,000 books, including rare manuscripts, that he had squirreled away around town. He survived the Soviet communists and the Islamic fundamentalists, and spent time in jail for anti-Islamic behavior. He despised the Taliban who burned his books. His family was wealthy by local standards, his opinions about women appeared liberal, he bought his wife western clothes in Iran, and derided the burka as a symbol of his beloved country's backwardness and oppression.

At home Seierstad discovered an altogether different Sultan, and for the most part her narrative reads like a cultural expose. She begins by telling the story of how Sultan took sixteen-year-old Sonya as his second wife, much to the grief of his first wife Sharifa. At home Sultan was an unapologetic tyrant toward everyone in his family. His two wives and daughters slaved away at cooking and cleaning. He consigned his twelve-year-old son to sell candy in a dark and dank stall that he called "the dreary room." When a poor carpenter stole some post cards from his shop to feed his seven children, Sultan was merciless. The book alternates between describing the particular abuse in Sultan's home, and that in broader Afghan culture. A first-grader, for example, learns the alphabet by memorizing the following: "I is for Israel, our enemy; J is for Jihad, our aim in life; K is for Kalishnikov, we will overcome; . . . M is for Mujahedeen, our heroes; . . . T is for Taliban. . . "

The Bookseller of Kabul captures everyday life in a country ravaged by twenty years of war and characterized by deep cultural conservatism. In an ironic postscript to the book's wild success, Sultan has sued Seierstad and her publisher for libel in a Norwegian court. He insists that his hospitality was abused, his personal life was slandered, and that his family has been endangered, so he has, in good western fashion, demanded what his lawyer has called "redress and compensation."