Book Notes

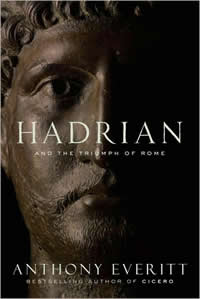

Anthony Everitt, Hadrian and the Triumph of Rome (New York: Random House, 2009), 392pp.

Anthony Everitt, Hadrian and the Triumph of Rome (New York: Random House, 2009), 392pp.

With critically acclaimed biographies of Cicero and Augustus to his credit, Anthony Everitt completes his triptych with a biography of the Roman emperor Hadrian (76–138 AD). It's a natural project for him in more ways than one. The book jacket indicates that he lives near Colchester — England's first recorded town, mentioned by Pliny the Elder in 77 AD, and founded by the Romans after they conquered Britain in 43 AD.

Orphaned at the age of ten when his father died, Hadrian became emperor of the empire's sixty million people in the year 117 when he was forty-one. His was the age of the Jewish revolt, the sack of Jerusalem and its temple, the Circus Maximus racecourse whose marble stands held 250,000 people, the eruption of Mount Vesuvius that buried Pompeii, the opening of the fabled Coliseum with its gladiatorial games, and militarist expansion that created an imperium sine fine (empire without end) that stretched from Spain to Persia and from North Africa to northern Britain.

"The prime challenge facing the biographer of Hadrian," Everitt admits, "is the inadequacy of the leading literary sources." As a consequence of this, in his narrative Hadrian does not even become emperor until halfway through the book, the focus being the larger background material of Roman life and politics. I appreciated Everitt's candor about what he considers historical fact or fiction in the ancient sources; he's more than willing to speculate, but he always tells you when he does. The result is a portrait of Hadrian as an architectural enthusiast (if amateur who irritated the experts), poet, dedicated hunter, constant traveler (he spent over half his twenty-year reign on the road), and deeply superstitious man of religion, magic, astrology, and Greek initiation rites. Although married to Sabina, Hadrian had a long and deep love for a young man named Antinous whom he met when the latter was fifteen years old. His villa near Tivoli contained at least forty statues of Antinous, and across the entire empire archaeologists estimate that there were at least 2,000 images of various sorts of Hadrian's boy love (115 of which survive).

Hadrian deserves special credit for two major accomplishments. First, and despite significant political opposition, he decisively stopped Rome's aggressive policies of military expansion, and even relinquished the lands of Armenia, Mesopotamia, Assyria, and Parthia that his predecessor Trajan had annexed. Second, Hadrian was a lover of all things Greek, and during his reign he managed through various means to unite the empire's Greek-speaking east and Latin-speaking west. Everitt thus concludes that Hadrian "has a good claim to have been the most successful of Rome's leaders." The book includes a comprehensive time line of Roman history and numerous black and white plates.