For Sunday April 24, 2022

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Psalm 118:14-29 or Psalm 150

Revelation 1:4-8

John 20:19-31

From Our Archives:

For earlier essays on this week's RCL texts, see the essay by Debie Thomas, This is My Body; and then the four essays by Dan Clendenin: We Must Obey God Rather Than Men; Sent for Peace; Remembering Rosa Parks: The Radical Faith of a Rebel Christian; and The Disciple of Doubt.

Dan Clendenin founded JWJ in 2004.

"I am the resurrection and the life. Whoever believes in me will live, even though he dies."

And then, as if Jesus anticipated our own incredulity two thousand years later—our nagging doubts, our honest questions, and our lingering disbelief at such a preposterous claim, he asked Martha a very pointed question: "Do you believe this?"

If I had one post-Easter prayer, a single prayer that expressed my many fragmentary prayers, it would be to live as if this truth were true. To believe that God's resurrection life will conquer all the demons of death that threaten us — like the barbaric violence in Ukraine that has killed thousands and displaced 10 million ordinary citizens, the scourge of our global pandemic, our environmental degradation of the earth, and the corrosive effects of political nihilism around the world.

|

|

The Raising of Lazarus by Duccio di Buoninsegna (1255-1319).

|

I would pray to follow in Martha's faith, "Yes, Lord, I believe that you are the Christ, the Son of God, who was to come into the world." And to confess with Peter in the reading from Acts 5 that "the God of our fathers raised up Jesus." To hear Jesus's encouragement to Thomas in John 20 this week: "be not unbelieving but believing." And to experience what Paul calls "the power of his resurrection" in his letter to the Philippians.

In my experience, this has been easier said than done. In fact, one of the more counterintuitive aspects of the earliest Christians stories, and one that gives me an odd sort of comfort, is how they describe a broad-based antipathy toward Jesus. Many people found lots of reasons to disbelieve.

Some people complained that Jesus told people not to pay their taxes. His family thought he was crazy. One village ran him out of town. He scorned religious traditions. He broke the boundaries of class, gender and ethnicity. As a result of these and other offenses, John says that "many of his disciples turned back and stopped following him."

This widespread unbelief shouldn't surprise us. After two thousand years of simplistic cliches, pious platitudes, and ecclesial bureaucratism, we forget how bitterly divisive Jesus was. He was the "rock of offense" that the builders rejected, the "stumbling block" over which they tripped. Paul conceded that he was "foolishness" to the Greek intelligentsia. Jesus was Isaiah's "despised and rejected" messiah. From Rome's political perspective, this religious renegade deserved his criminal execution.

|

|

The Raising of Lazarus, illuminated manuscript, 1504.

|

The resurrection story in particular subverts any idea that Christianity can be dumbed down to a safe program of ethical uplift. It makes a stupendous claim, what the English poet Sir John Betjeman called "this most tremendous tale of all." For a post-modernist, the resurrection story is a dreadful and naive claim of an objectively true Grand Narrative that is valid for all people, times, and places.

It's a contemporary conceit to argue that illiterate peasants in a pre-scientific culture were so gullible that they believed in a crude superstition like the resurrection of the dead. Disbelief didn't begin with the eighteenth-century Enlightenment, nineteenth-century Darwinists or Marxists, with twentieth-century post-modernists, or contemporary atheists like Richard Dawkins, Daniel Dennett, and Sam Harris. Only our modern hubris could congratulate itself on such an anachronistic conclusion.

Many people doubted the rumors of resurrection. The first to disbelieve were those who were closest to Jesus. When the women told the eleven disciples that they had seen the risen Lord, Mark writes that "they did not believe it." Luke is more blunt: "They did not believe the women, because their words seemed to them like nonsense."

Two witnesses who were walking the seven miles from Jerusalem to Emmaus reported their encounter with the resurrected Jesus to the eleven, "but they did not believe them either." Jesus then "rebuked them for their lack of faith and their stubborn refusal to believe." Thomas became the most famous Doubter, while the last paragraph of Matthew ends with the observation that there were still "some who doubted."

When some Athenians in the Areopagus heard Paul proclaim the resurrection, "they sneered" at the "strange demons" he advocated, and ridiculed him as a "rag picker." Porcius Festus, the Roman governor of Judea under Nero, admitted that he was "at a loss" to know what to do with the prisoner Paul: "They did not charge him with any of the crimes I had expected. Instead, they had some points of dispute with him about a dead man named Jesus who Paul claimed was alive."

Peter found it necessary to deny that he preached a "cleverly invented tale." Paul describes believers in Corinth who argued that "there is no resurrection of the dead" for anyone at all — believers who did not celebrate Easter. In the first pagan account of Christianity, Pliny the Younger wrote a letter to the Roman Emperor Trajan (c. 112 AD) in which he refers to their "depraved, excessive superstition."

|

|

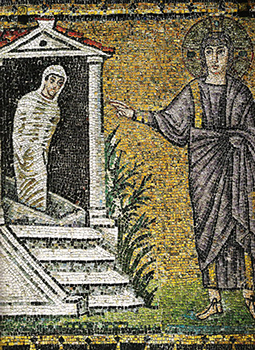

The Raising of Lazarus, sixth-century mosaic, Sant' Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna, Italy.

|

Disbelief in the resurrection, among both the followers and detractors of Jesus, shapes part of our origin story. But gradually, somehow, among a growing movement of people from all segments of society, doubt and confusion gave way to a deep-seated conviction. As is often the case with many important aspects of life, this conviction about the resurrection was easier to describe than to fully explain. Paul called it unfathomable and inexpressible. It remains a fascinating question how a despised and insignificant Jewish sect became the first and largest global religion.

There eventually emerged a consensual tradition of "first importance" that Paul said he had received, preached, and passed on to others — that Christ died, was buried, raised on the third day, and that he appeared publicly to many people. "This is what we preach, and this is what you believed," Paul wrote to the Corinthians. By that definition, other interesting and important matters were relegated to secondary importance.

And so Jesus's question to Martha ricochets down through history to us today: Do you believe this? And if you do, what difference does it make? What would resurrection faith look and feel like in the twenty-first century? What would it mean to live as if this truth were true?

Resurrection is a future hope that is presently unseen. But this future hope isn't a cop-out or a fantasy that makes us withdraw from the world; it's a concrete orientation that shapes everything we do and are. In the Ukraine right now, president Volodymyr Zelensky has reminded us of how hope in a hopeless situation exerts a powerful force. As we wait for the Not Yet of final resurrection, we live in the Already of what Jesus called an "abundant life."

Acts 5:20 for this week calls us to live "the full message of this new life." I love that pregnant phrase. In his poem The Mad Farmer Liberation Front, the poet-farmer Wendell Berry urges us to "practice resurrection." We can practice resurrection in many different ways (as his poem illustrates). Here's a good beginning:

* welcome the stranger

* visit the prisoner

* shelter the homeless

* feed the hungry

* forgive one another

* care for the widow

* imitate the children

* speak up for those who have no voice

* honor and protect the dignity of every human being

In short, to practice resurrection, choose life!

On this side of resurrection, we experience God's power and inner transformation as a significant beginning, something that is real, true, and discernible. Paul describes it with the Greek word metamorphosis. He said that it was "the life that is truly life indeed." But it is only an inauguration and not a culmination, a partial beginning rather than a total fulfillment.

|

|

The Resurrection of Lazarus, 12th-13th century, Athens.

|

When Paul mentions the "power of the resurrection," he includes "the fellowship of his sufferings." He spoke openly of his own "conflicts without and fears within." He said that now our knowledge is partial, only a part of a part, like a "dim reflection" in a murky mirror (literally, "in a riddle"). We "groan inwardly and are burdened," and still live in the long shadow of the preacher Qoheleth.

Paul uses two metaphors to make this point, one from farming and one from finance. In this life we experience the “first fruits” of the Spirit's power and presence, not the full harvest. Or again, right now we receive only a partial down payment of God's full resurrection power, but this partial deposit is a promissory note for our full redemption in the future.

I like how Frederick Buechner puts it in his book A Room Called Remember (1984): "There is deliverance, to use that beautiful old word, and Christians are people who through such now-and-then, here-and-there visions as they've had, through Christ, have been delivered just enough to know that there's more where that came from, and whose experience of the little deliverance that has already happened inside themselves and whose faith in the deliverance still to happen is what sees them through the night."

A Weekly Prayer

I Thank You God by e.e. cummings (1894-1962)

i thank You God for most this amazing

day:for the leaping greenly spirits of trees

and a blue true dream of sky;and for everything which is natural which is infinite which is yes (i who have died am alive again today,

and this is the sun's birthday;this is the birth day of life and love and wings:and of the gay great happening illimitably earth)

how should tasting touching hearing seeing breathing any—lifted from the no

of all nothing—human merely being

doubt unimaginable You?

(now the ears of my ears awake and

now the eyes of my eyes are opened)

Edward Estlin Cummings’ works include some 3,000 poems, two autobiographical novels, four plays, and numerous essays. He is famous for his idiosyncratic spelling, punctuation, syntax, spacing, capitalization, and line breaks.

Dan Clendenin: dan@journeywithjesus.net

Image credits: (1) Wikimedia.org; (2) Wikipedia.org; (3) Wikipedia.org; and (4) Wikimedia.org.