For Sunday January 10, 2016

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Isaiah 43: 1-7

Psalm 29

Acts 8:14-17

Luke 3:15-22

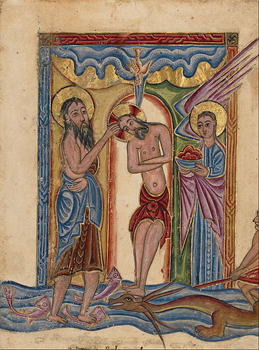

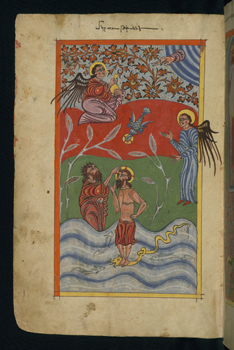

Epiphany. The word comes from the Greek, "epiphaneia," meaning "appearing" or "revealing." During this brief season between Advent and Lent, we leave mangers and swaddling clothes behind, and turn to stories of shimmering revelation. Kings and stars. Doves and voices. Water. Wine. Transfiguration.

In Celtic Christianity, Epiphany stories are stories of "thin places," places where the boundary between the mundane and the eternal becomes permeable. God parts the curtain, and we catch glimpses of his love, majesty, and power. Epiphany calls us to look beneath and beyond the ordinary surfaces of our world, and discover the extraordinary. To look deeply at Jesus, and see God.

The problem? I have never discovered a portentous star in the East. I have never seen the Spirit descend like a dove, or heard a divine Voice in the clouds. I've never watched water become wine, or seen Jesus's clothes blaze white on a mountaintop. Though I have professed belief in a self-revealing God all my life, I have not experienced him in any of the ways the Epiphany stories describe. As St. John puts it, I belong to "a people who walk in darkness."

|

My experience might be unique, but I doubt it. I don't know many 21st century Christians who bask in signs and wonders, who complain that God talks too much, or butts into their lives too often. But I know plenty of believers who experience God as hidden and silent. These are faithful people who long for epiphany — not just for a season, but for lifetimes.

So I stand at the edges of this week's Gospel reading — Luke's account of Jesus's baptism — and find myself afraid to leap. How shall I bridge the gap between an ancient Voice and a modern silence? Heaven opened. A dove descended. God spoke. Really? I want to believe this. I do.

But to accept the supernatural in Scripture is to plunge into a sea of hard questions. If God spoke audibly in the past, why doesn't he do so now? If he does, why haven't I heard him? Is God angry at me? Has he retreated? Changed? Left?

Or are the ancient stories of Epiphany figurative? Was the dove, in fact, just a dove, and the voice from heaven no more than a nicely timed windstorm? When we speak of epiphanies, are we really just trucking in metaphor? Perhaps God should be in scare quotes. I had a "spiritual experience." I felt "God." He "spoke" to me. Isn't it embarrassing nowadays to believe in miracles?

According to Christian historian John Dominic Crossan, the baptism story was an "acute embarrassment" for the early Church, too, but for reasons very different from our modern ones. What scandalized the Gospel writers was not the miraculous, but the ordinary. Doves and voices? All well and good — but the Messiah placing himself under the tutelage of a rabble-rouser like John? God's incarnate Son receiving a baptism of repentance? Perfect, untouchable Jesus? What was he doing in that murky water, aligning himself with the great unwashed? And why did God the Father choose that sordid moment to part the clouds and call his Son beloved?

I suppose every age has its signature difficulties with faith. When we're not busy flattening miracle into mirage, we're busy instead turning sacrament into scandal. After all, what's most incredulous about this story? That the Holy Spirit became a bird? That Jesus threw his reputation aside to get dunked alongside sinners? Or that God looked down at the very start of his Son's ministry and called him Beloved — well before Jesus had accomplished a thing worth praising?

|

Let me ask the question differently: what do we find most impossible to believe for our own lives? That God appears by means so familiar, we often miss him? That our baptisms bind us to all of humanity — not in theory, but in the flesh — such that you and I are kin, responsible for each other in ways we fail too often to honor? Or that we are God's Beloved — not because we've done anything to earn it, but because our Father has spoken?

Here's my real problem with Epiphany: I always, always have a choice — and most of the time, I don't want it. I expect God's revelations to bowl me over. I expect the thin places to dominate my landscape, such that I am left choice-less, powerless, sinless. Freed of all doubts, and pulsing with faith.

But no. God has not insulted humanity with so little agency; we get to choose. No matter how many times God shows up, I'm free to ignore him. No matter how often he calls me Beloved, I can choose self-loathing instead. No matter how many times I remember my baptism, I'm capable of dredging out of the water the very sludge I first threw in. No matter how often I reaffirm my vow to seek and serve Christ in all persons, I'm at liberty to reject you and walk away.

The stories of Epiphany are stories of light, and yet quite often, they end in shadow. The Visitation of the Magi leads to the Slaughter of the Innocents. Jesus's baptism drives him directly into the wilderness of temptation and testing. Soon after he's transfigured, he dies. There is no indication, anywhere in Scripture, that revelation leads to happily ever afters. It is quite possible to stand in the hot white center of a thin place, and see nothing but my own ego.

Yet we speak so glibly of faith, revelation, and baptism. As if it's all easy. As if what matters most is whether we sprinkle or immerse, dunk babies or adults. As if lives aren't on the line. Until Christianity became a state-sanctioned religion in the 4th century A.D, no convert received the sacrament of baptism lightly; he knew the stakes too well. To align oneself publicly with a despised and illegal religion was to court persecution, torture, and death.

I don't know about you, but I find so much of this maddening. How much nicer it would be if the font were self-evidently holy. But no — the font is just tap water, river water, chlorine. The thin place is a neighborhood, a forest, a hilltop. The voice that might be God might also be wind, thunder, indigestion, or delusion. Is the baby divine? Or have we misread the star? Is this the very life and body of God's Son? Or is it a mere hunk of bread? A jug of wine?

|

What I mean to say is that there is no magic — we practice Epiphany. The challenge is always before us: look again. Look harder. See freshly. Stand in the place that might possibly be thin, and regardless of how jaded you feel, cling to the possibility of surprise. Epiphany is deep water — you can't dip your toes in. You must take a breath and plunge. Yes, baptism promises new life, but it always kills before it resurrects.

What reason for hope, then? What shall we hang onto in this uncertain season of light and shadow? New Testament scholar Marcus Borg suggests that Jesus himself is our thin place. He's the one who opens the barrier, and shows us the God we long for. He's the one who stands in line with us at the water's edge, willing to immerse himself in shame, scandal, repentance, and pain — all so that we might hear the only Voice that can tell us who we are and whose we are in this sacred season. Listen. We are God's own. God's children. God's pleasure. Even in the deepest water, we are the Beloved.

Image credits: (1) Wikipedia.org; (2) Wikipedia.org; and (3) Flickr.com.