For Sunday November 15, 2015

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

1 Samuel 1:4–20 or Daniel 12:1–3

1 Samuel 2:1–10 or Psalm 16

Hebrews 10:11–14 (15–18), 19–25

Mark 13:1–8

About a month ago when I turned sixty, I finished a book by Marcus Borg called Convictions: How I Learned What Matters Most (2015). Borg wrote about thirty books across his career. In some ways, he wrote the same book over and over. Convictions was his last one, published just before he died at the age of seventy-two from idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Borg was one of a very few New Testament scholars who wrote simple books for a general audience. He wasn't embarrassed to declare his passion for a life of faith. He shared his own journey from a conservative Lutheran upbringing to a "progressive" Christianity. And he was both forceful and irenic in presenting his views.

Convictions originated with his seventieth birthday, and a sermon that Borg gave for the occasion. He begins by reflecting on that milestone. Turning seventy, he wrote, "has not been grim." He says that turning sixty was much harder. It felt old. Ouch!

|

|

Hannah and Elkanah, the Winchester Bible, 12th century.

|

"At seventy I primarily feel gratitude. Each extra day feels like lagniappe, a Cajun French word that means 'something extra' — like the cherry on top of the whipped cream on top of the hot fudge on top of the ice cream. I enjoy my days more than I ever have. At seventy, life is too short to spend even an hour feeling preoccupied or grumpy or out of sorts."

I experienced my own mixed feelings at milestone sixty. I can only aspire not to feel grumpy for even an hour (maybe when I turn seventy?). At sixty, I have a greater sense of the limits imposed by life. I now know that not every problem can be fixed. That pain and suffering run deep, and nobody gets a free pass. I get discouraged watching the nightly "news" with its surreal mix of the tragic and the trivial.

When I turned fifty, I had a big party. This birthday was more deliberately downscale. I had a few friends over for dinner. I did my first-ever triathlon with my son. And thanks to a friend, we gathered our family at the beach.

What I most felt about turning sixty was a deep sense of gratitude. I resonated with what Borg wrote about turning seventy. I feel increasingly grateful for the gift of life, with all its blessings and sorrows, and despite all that we see in the world.

I've grown to love the eucharistic prayer of Great Thanksgiving that we confess every Sunday morning at my church: "It is right, and a good and joyful thing, always and everywhere to give thanks to you, Father Almighty, creator of heaven and earth."

And so, in a letter to JwJ donors last month, I quoted the poem "Otherwise" by Jane Kenyon (1947-1995). My wife gave me this poem some time ago after hearing it at Stanford.

|

|

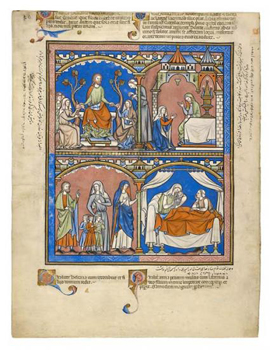

Hannah's Grief; Hannah's Prayer; The Road Home; Samuel. Old Testament miniatures. Paris,1240s.

|

I got out of bed

on two strong legs.

It might have been

otherwise. I ate

cereal, sweet

milk, ripe, flawless

peach. It might

have been otherwise.

I took the dog uphill

to the birch wood.

All morning I did

the work I love.At noon I lay down

with my mate. It might

have been otherwise.

We ate dinner together

at a table with silver

candlesticks. It might

have been otherwise.

I slept in a bed

in a room with paintings

on the walls, and

planned another day

just like this day.

But one day, I know,

it will be otherwise.

This is a short poem with short sentences and short words, almost all of which are one syllable. It considers the simplest pleasures of life — sleep, food, the family dog, and work. The ordinary routines of a normal day, nothing more than eating a bowl of cereal, call us to pay attention. To cultivate gratitude. And to remember, in the words of the last line, the brevity of life.

|

|

Elkanah and his two wives, the Rochester Bible, c. 1125. English illuminated manuscript. The British Library.

|

The story of Hannah about the birth of Samuel in 1 Samuel echoes similar stories about barren women who gave birth to a special child late in life due to the special favor of God—Sarah, Rebekah, Rachel, Samson's unnamed (!) mother, and Elizabeth in Luke's gospel.

And is there anything that evokes joy and gratitude more than the birth of a baby?

Hannah's Song exudes gratitude and thanks: "My heart rejoices in the Lord; / in the Lord my horn is lifted high." This might well be a literary model for Mary's Magnificat.

God reversed Hannah's bad fortune. He remembered her "bitterness of soul... much weeping… deep troubles, … and great anguish." He alone is in control. And so in 1 Samuel 1:20 Hannah named her baby Samuel, "Because I asked the Lord for him." The name Samuel means "God has heard."

Joy and gratitude in our broken world can sometimes strike a false note. They can feel platitudinous and glib. Isn't it presumptuous to claim God's personal favor? A narcissistic indulgence? And what about the millions who suffer and all the unanswered prayers?

Those are important questions. But the audacious idea of the personal care of a transcendent God isn't an evangelical invention. It's a gift of the Hebrew imagination.

I've always loved the wise words of the fourteenth-century English mystic Julia of Norwich: "The greatest honor we can give almighty God is to live gladly because of the knowledge of his love."

Image credits: (1) MetMuseum.org; (2) TheMorgan.org; and (3) Seattle Pacific University.