From Our Archives

Debie Thomas, I Will Make (2021) and Fishing for People (2018) ; and Dan Clendenin, Evangelical: When Labels Are Libels (2015) ; and "The Time Has Come": Martin Luther King Day (2009).

For Sunday January 21, 2024

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Readings:

Jonah 3:1–5, 10

Psalm 62:5–12

1 Corinthians 7:29–31

Mark 1:14–20

This Week's Essay

Now after John was arrested, Jesus came to Galilee, proclaiming the good news of God, and saying, "The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God has come near; repent, and believe in the good news."

I don't know about you, but I find it hard to watch the news these days. My wife and I like to watch the PBS NewsHour while eating dinner, but sometimes I have to turn away, or even turn off the television. The violent images and lurid stories are just too much.

There's a saying in the news industry that "if it bleeds it leads." The news as tragedy is a highly lucrative commodity that is predicated upon being bad. And the badder the better. This is not an accident, it's by design. That's why Leslie Moonves, the CEO of CBS, said of Trump's 2016 presidential run, "It may not be good for America, but it's damn good for CBS."

News as infotainment is designed to be addictive, distractive, polemical, and partisan. It's an immersive totality that is almost impossible to escape. Sophisticated algorithms push stories to our digital devices that reinforce our biases. No story is too insipid if it drives ratings. And now we have sophisticated AI deepfake news.

|

Into this total noise of bad news, the gospel of Mark for this week hits like a sledge hammer: "Jesus came to Galilee, preaching the Good News of God."

The very first sentence of Mark reads, "the beginning of the euanggelion of Jesus Christ." A few paragraphs later, in this week's reading, Mark describes how after living in total obscurity for thirty years, Jesus burst onto the public scene "proclaiming the euanggelion of God, saying, 'The time has come. The kingdom of God is near. Repent and believe the euanggelion.'" Jesus himself, it turns out, embodies the euanggelion, the good news or gospel of God.

This word euanggelion and its derivatives occur about eighty times in the Greek New Testament. That's why Martin Luther thought that the Latin version of the word, evangelium, was the perfect word to describe his radical movement that spread like wild fire across sixteenth-century Europe. And then, from the original Greek to medieval Latin to his native German, there came Luther's evangelische kirche, in contrast to what he thought were the distortions, corruptions, and accretions of medieval Catholicism that had obscured the simple good news of God in Jesus.

There are numerous competitors and imitators when it comes to "good news." Political power, whether ancient or modern, whether conservative or liberal, seeks to control "the news." It claims to be the single source of a saving message or "good news," the sole possessor of all truth. During my four years as a visiting professor in Moscow (1991–1995), the official newspaper of Soviet communism was called Pravda ("truth").

|

Or consider this inscription from Asia Minor from about 9 BCE that describes Caesar Augustus: "The most divine Caesar…we should consider equal to the Beginning of all things… Whereas the Providence which has regulated our whole existence…has brought our life to the climax of perfection in giving to us the emperor Augustus…who being sent to us as a Savior, has put an end to war… The birthday of the god Augustus has been for the whole world the beginning of good news (euanggelion)."

I wasn't a fan of Pope Benedict XVI, but I love what he said about this Greek word euanggelion, and how it deconstructs and subverts the paean of praise to Caesar Augustus. In his book Jesus of Nazareth (pp. 46-47), he writes:

Both Evangelists designate Jesus’s preaching with the Greek term evangelion — but what does that actually mean?

The term has recently been translated as “good news.” That sounds attractive, but it falls far short of the order of magnitude of what is actually meant by the word evangelion. This term figures in the vocabulary of the Roman emperors, who understood themselves as lords, saviors, and redeemers of the world. The messages issued by the emperor were called in Latin evangelium, regardless of whether or not their content was particularly cheerful and pleasant. The idea was that what comes from the emperor is a saving message, that it is not just a piece of news, but a change of the world for the better.

When the Evangelists adopt this word, and it thereby becomes the generic name for their writings, what they mean to tell us is this: What the emperors, who pretend to be gods, illegitimately claim, really occurs here — a message endowed with plenary authority, a message that is not just talk, but reality. In the vocabulary of contemporary linguistic theory, we would say that the evangelium, the Gospel, is not just informative speech, but performative speech — not just the imparting of information, but action, efficacious power that enters into the world to save and transform. Mark speaks of the “Gospel of God,” the point being that it is not the emperors who can save the world, but God. And it is here that God’s word, which is at once word and deed, appears; it is here that what the emperors merely assert, but cannot actually perform, truly takes place. For here it is the real Lord of the world — the living God — who goes into action.

And then comes a second Greek word in the gospel for this week. Jesus said that "the kairos has come." Kairos denotes a critical juncture, a divine appointment or intervention, in contrast to prosaic chronos or everyday "clock time." With chronos you might forget what time your appointment is, whereas kairos provokes a radical response, an urgent choice, or a fundamental reorientation. It invites us to "repent," says Mark, to change our minds and actions, just like the Ninevites did in this week's Old Testament reading from Jonah.

|

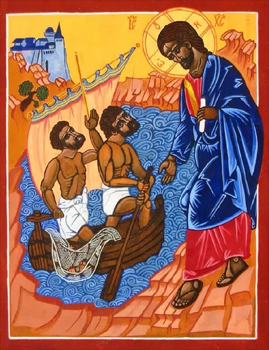

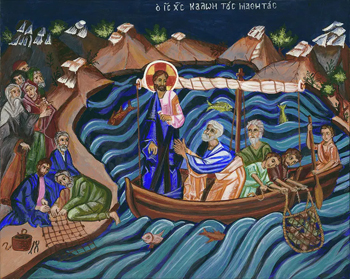

When he announced "the euanggelion of God," Jesus identified God's kingdom with his own person. That's why he invited Simon Peter and his brother Andrew, "Come, follow me." Mark is unambiguous about their unequivocal response: "At once they left their nets and followed him." And to punctuate his point, Mark adds that "when they had gone a little farther" Jesus called a second set of brothers, James and John, who were at work in their boats. They too left everything at once to follow Jesus — their father, the hired help, the boat and their nets.

Jesus proclaimed that "God's kairos has come and his kingdom is near. Repent and believe the euanggelion." In this week's epistle, written about thirty years after Jesus, Paul used remarkably similar language in his letter to the Corinthians: "The kairos is short… this world in its present form is passing away." Scholars debate what Paul meant when he said that "the time has been shortened" — maybe his death was imminent, that he believed Jesus was to return soon, or that he was alluding to specific matters at Corinth.

Whatever he meant, there's no ambiguity in the response that he urged due to the crisis of the kairos. He cautioned against any postponement, entanglements, or distractions. He eliminated any middle ground and called for an either/or decision. The married, the mourning, the exuberant, the buyers and sellers should all live "as if" the normal canons of chronos did not adhere. The fulfillment (Jesus) and foreshortening (Paul) of God's kairos meant that we should no longer live "business as usual." The announcement of God's euanggelion in Jesus should elicit a radical revolution in life's journey.

In the introduction to the book Daniel Berrigan: Essential Writings (2009), the editor John Dear describes how Berrigan (1921–2016) engaged the bad news of the world rather than ignore it, and yet how he immersed himself even more deeply in the good news of God in Christ. Make your own story fit into the story of Jesus, he liked to say. Live as if the truth were true.

At the height of the American war in Iraq, when he was eighty-five years old, Berrigan confided to Dear, "I've been maintaining a new discipline. First, I get as little of the bad news as possible. I only look at the New York Times once a week, if that, and occasionally BBC TV. Second, I spend more time than ever with the good news, reading and meditating on the Gospel every morning, to be with Jesus." Amen to that.

Weekly Prayer

Daniel Berrigan

A Prayer to the Blessed Trinity

I'm locked into the sins of General Motors

My guts are in revolt at the culinary equivocations of General Foods

Hang over me like an evil shekinah, the missiles of General Electric.

Now we shall go from the Generals to the Particulars.

Father, Son, Holy Ghost

Let me shake your right hands in the above mentioned order

Unmoved Motor, Food for Thought, Electric One.

I like you better than your earthly idols.

You seem honest and clear-minded and reasonably resolved

To make good on your promise.

Please: owe it to yourselves not less than to us,

Warn your people: beware of adulterations.From Daniel Berrigan, And the Risen Bread; Selected Poems, 1957–1997 (1998).

Dan Clendenin: dan@journeywithjesus.net

Image credits: (1) Circle of Hope; (2) Ancient Faith Ministries; and (3) Wordpress.com.