From Our Archives

Debie Thomas, Astounded (2021); The Exorcist in the Synagogue (2018); and Dan Clendenin, There is No Them (2015).

For Sunday January 28, 2024

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Deuteronomy 18:15-20

Psalm 111

1 Corinthians 8:1-13

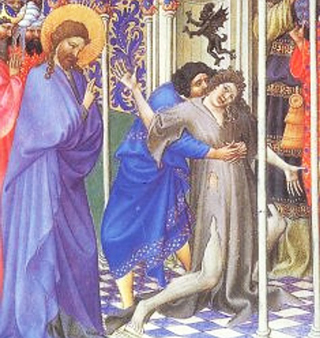

Mark 1:21-28

This Week's Essay

The reading from Deuteronomy this week raises a question that is obvious, urgent, devilishly difficult, and that is as relevant today as when it was asked three thousand years ago: "How can we know when a message has (not!) been spoken by the Lord?" (18:21). Plenty of people today claim to speak in God's name, and to know the divine mind. Consider just three examples.

Hamas and Hezbollah ("Party of God") would annihilate Israel.

For the medieval crusaders, genocide and forced conversions, butchery and baptisms, were equally works of God. The church justified and sanctified the Crusades, and even canonized them as meritorious deeds that earned one remission of sins and eternal salvation.

A few years ago I watched a history of the Aztec empire on public television that described in graphic detail their practice of human sacrifice. In 1487, the Aztecs sacrificed thousands of people in four days at the consecration of the Great Pyramid of Tenochtitlan (today the center of Mexico City).

Genocide, holy wars, child sacrifice, widow burning, caste systems, female genital mutilation, witch hunts, ritual abuse, ethnic cleansing, suicide bombers, apartheid, defending slavery, and mass suicides — the list of religious violence claiming God's support is depressingly long, not to mention all the god-talk that is merely idiotic and insipid. And so the question from Deuteronomy 18: "How can we know when a message has been truly spoken by the Lord?" In the language of 1 John 4:1, we have to "test the spirits."

|

We can start with something very simple and extremely important — the earnestness of a prophet is a poor criterion to determine who truly speaks for God. Sincerity is not a criterion of truth. At the end of his thousand-page history of the Crusades called God's War, Christopher Tyerman warns of the dangers of naievete: "It is a fond myth of the religious that piety excludes greed, coercion, conformity and lack of reflection, that it is freestanding. The language of transcendence should not distract or dupe."

Deuteronomy 18 suggests two ways to test the spirits.

First, the reading describes a false prophet as "presumptuous" (18:20, 22). To be presumptuous is to be brazen, or to transgress proper boundaries. I'm always amazed at how casually people speak about God, as if he were a Good Buddy. In contrast to such casual confidence, a true prophet is circumspect — cautious and careful, guarded and discreet, modest to a fault.

Moses gave many excuses for why he couldn't be a prophet. In Isaiah's terrifying vision of the Holy God "high and lifted up," a burning coal purified his unclean lips. Jeremiah insisted that he was too young to become a prophet and that he "did not know how to speak." Paul wondered aloud "who is adequate for these things," given that the heavenly treasure is in earthen vessels.

Presumption violates the third commandment by misusing the name of the Lord, in contrast to circumspection, as in the Jewish tradition of honoring the mysterious, the inexpressible, and the inviolable name of "God" (YHWH) by not even pronouncing it. Instead, they substitute the word "adonay" or "Lord." Or sometimes they will refer to God as Hashem — "The Name." The Name that no one can name.

True prophets who are circumspect speak with an acute sense of the audacity of what they are attempting. They are painfully aware of the presumption inherent in claiming to speak for God. Who in their right mind would make such claims given the combination of human frailty and divine mystery? Every sane preacher has experienced the dread and shock of their preposterous calling — in some stumbling and bumbling way to speak a word that is true to God. Such is the paradox and burden of prophecy, observed Martin Buber: "It is laid upon the stammering to bring the voice of Heaven to Earth."

This "holy hesitancy" is well-founded. In Deuteronomy the penalty for false prophecy was death (18:20). That's a sobering reminder for we god-talkers. In the epistle for this week Paul warns believers who were overly confident about their Christian knowledge: "The person who thinks he knows something does not yet know as he ought to know" (1 Corinthians 8:2).

|

Whereas some ministries promote personality cults, simplistic formulas, and authoritarian appeals, the early desert monastics actively shunned clerical responsibility. They were decidedly reluctant to speak for God. John Cassian (c. 360–c. 435) judged it a trick of the devil to "inveigle us into desiring the holy clerical office under the pretext of edifying many." Evagrius (c. 345–399) described clerical aspiration as "the source and root of the love of power."

When a saint asked Abba Theodore, "Speak a word to me for I am perishing," the old man replied sorrowfully, "I myself am in danger. So what can I say to you?" For these early ascetics, renunciation, obedience, and confession of thoughts to an elder were a necessary check on trusting your own judgment—"of all evil suggestions, the most terrible" (Isidore the Priest). Uncritical acceptance of your own ideas, impulses, and inclinations, along with all forms of overzealous piety, were sure signs of spirituality run amuck.

In addition to "presumption," Deuteronomy says that we can identify a false prophet by their "detestable practices" (18:9, 12). Israel was to categorically reject the "detestable ways" of pagan nations. "Let no one be found among you who sacrifices his son or daughter in the fire, who practices divination or sorcery, interprets omens, engages in witchcraft, or casts spells, or who is a medium or spiritist or who consults the dead" (Deuteronomy 18:10–11).

It would be instructive to identify our own "detestable practices" that are peddled by religion today. I began this essay with three examples: genocide, holy war, and child sacrifice.

In contrast to the "detestable practices" of false prophets, God promised to raise up a true prophet like Moses. "You must listen to him" (18:15). At the simplest level, there arose in Israel the office and function of the prophets; their job was not so much to fore-tell the future as to forth-tell the present from God's perspective. But even within Israel some false prophets imitated the detestable practices that they were supposed to reject. Jeremiah, for example, thundered againt the "reckless lies and false hopes" prophesied by Israel's religious leaders (Jeremiah 23:23–29).

In the epistle this week, Paul says that claims of divine knowledge must be authenticated with concrete deeds of love: "Knowledge puffs up, but love builds up" (1 Corinthians 8:1). In Mark for this week, the people were "amazed" at Jesus's "authority" and his "new teaching." In stark contrast to the religious establishment, the "authority" of Jesus demonstrated itself by fostering human wholeness when he healed a man (Mark 1:21–28). James writes that "true and undefiled religion" cares for widows and orphans.

|

Here too the ruthless realism of the monastics can save us from "detestable practices" that masquerade as true religion. Those grizzled monks experienced every sort of pompous pronouncement, spiritual fraud and pious pretense. They knew what it meant for a deluded believer to be "deceived by his innumerable revelations and [wrongly] believe that he was a messenger of righteousness." Their spiritual radars were especially sensitive to what Cassian called "specious authority" and loveless judgmentalism.

So, we must test the spirits. Jesus repeatedly warned that "many" would come in his name who were false prophets, "blind guides," and hypocrites. "Watch out, " he warned, "be on your guard!" Paul warned the early churches about "savage wolves," false prophets with "depraved conduct," and "pseudo-apostles" who distorted the gospel for "dishonest gain."

The false prophet, then, is characterized by presumption, degradation, dehumanization, and detestable practices. The true prophet is marked by circumspection and compassion, and fosters human health and wholeness.

I've made my share of cringeworthy remarks. Thank God I was not on television, nor did I command an audience of millions. I do believe that God speaks today, but given the cacophony of religious voices ranging from the terrifying to the godly, hearing what He says demands that we distinguish between the signal and the noise. We must test the spirits.

For further thought: Ten Warning Signs That Religion Has Become Evil.

Weekly Prayer

C.S. Lewis

He whom I bow to only knows to whom I bow

When I attempt the ineffable Name, murmuring Thou,

And dream of Pheidian fancies and embrace in heart

Symbols (I know) which cannot be the thing Thou art.

Thus always, taken at their word, all prayers blaspheme

Worshiping with frail images a folk-lore dream,

And all men in their praying, self-deceived, address

The coinage of their own unquiet thoughts, unless

Thou in magnetic mercy to Thyself divert

Our arrows, aimed unskillfully, beyond desert;

And all men are idolaters, crying unheard

To a deaf idol, if Thou take them at their word.

Take not, O Lord, our literal sense. Lord, in thy great

Unbroken speech our limping metaphor translate.C.S. Lewis (1898–1963) was a Professor of Medieval and Renaissance Literature at Oxford and Cambridge universities. In 2013, on the 50th anniversary of his death, he was honored with a memorial stone in the Poets’ Corner of Westminster Abbey, alongside Chaucer, Shakespeare, Milton, Handel, Dickens, and many others.

Dan Clendenin: dan@journeywithjesus.net

Image credits: (1) Wikipedia.org; (2) T.A. Donnelly; and (3) Wikipedia.org.