From Our Archives

Dan Clendenin, The Pharisee and the Tax Collector (2016); Debie Thomas, On Confession (2019).

For Sunday October 23, 2022

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Joel 2:23–32 or Jeremiah 14:7–10, 19–22

Psalm 65 or Psalm 84:1–7

2 Timothy 4:6–8, 16–18

Luke 18:9–14

This Week's Essay

My wife's stepfather grew up on a farm in Kansas. I can remember him describing something like the locust plague from this week's prophet Joel: "What the locust swarm has left, the great locusts have eaten. What a dreadful day! Before them the land is like the garden of Eden, behind them a desert waste."

The prophet Joel makes only a brief appearance in the biblical drama, and even then he's shrouded in obscurity. All that we know about him comes from his micro-prophecy, but that doesn't tell us much since it's only five pages long.

His name means “Yahweh is God,” but other prophets claim that moniker. He says he's the son of Pethuel, but that's no help since we know nothing about his father. His several references to the temple suggest that Joel lived in Jerusalem, but that's only conjecture. Even the time of his prophecy is murky, with scholars suggesting dates as early as 835 BC and as late as 200 BC.

Nonetheless, Joel is a good example of the dual role that prophets played in the history of Israel, and how they can speak to us today across the centuries.

First, Joel did more "forth-telling" about the present than "fore-telling" about the future. The business of the prophets was more prognosis than prediction. Prophets discerned with unusual clarity the significance of current events and the circumstances of God's people. Based upon their diagnosis, they spoke a word from God to provoke his people to change. By speaking God's word to our world, the prophets call us to radical transformation in the here and now.

|

|

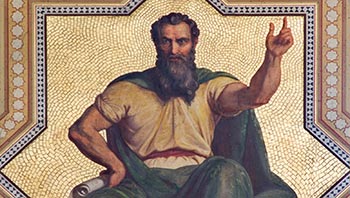

The prophet Joel by Michelangelo, the Sistine Chapel.

|

Joel takes an environmental catastrophe and interprets it as an act of God. "The locust plague that we are now experiencing," he says, "is an act of divine judgment calling us to repentance, renewal and redemption!"

The locust plague devastated the land, the economy and the people. Bark was stripped from trees, food vanished, seeds shriveled, granaries stood empty, cattle moaned from hunger and thirst, and streams evaporated into dry creek beds. With memories of the divine plagues of Moses, Joel interprets this natural disaster as a spiritual sign. He calls it a “day of the Lord," a phrase that he uses six times. Israel, he says, should understand the plague as a divine invitation to turn to Yahweh for redemption.

But the prophets did more than "forth-tell" God's judgment. They also cast a positive vision for the people's future. The rains will return. The vats will overflow with new wine. The threshing floor will be filled with grain.

"Your old men shall dream dreams," said Joel, "your young men will see visions." In addition to prophetic critique, the prophets offered pastoral comfort. They kept the dreams of God's people and his kingdom alive in times of disaster and discouragement.

Walter Brueggemann captures this dual role of the prophets nicely when he says that the prophets both criticized and energized. On the one hand, they disturbed the status quo. They questioned the reigning order of things. They viewed the normal state of affairs in a different light, and advocated a new way of seeing and living — personally, socially, spiritually, economically, politically, in short, in every dimension of life. The prophets afflicted the comfortable and the complacent.

But they also comforted the afflicted. They intended to “generate hope, affirm identity, and create a new future," says Brueggemann. They offered more than a negative critique; they were also about positive affirmation and encouragement. This is especially evident when Israel — God's elect! — was destroyed by the pagan nations of Assyria (722 BC) and Babylon (586 BC). How could that happen? Didn't it suggest the failure of God's plan, the abandonment of his people?

|

|

The prophet Joel preaching, National Library of the Netherlands.

|

When Israel was in exile, feeling forgotten by Yahweh, the prophets consoled them with hope. “Do not be afraid," says Joel. If you've ever felt despair over a hopeless situation, the prophets have a word for you. Yes, they dished out the vinegar; but they also gave us honey for the heart.

Prophetic critique demands radical change. As in now. "Wake up!" writes Joel, "Weep! Wail! Blow the trumpet in Zion; sound the alarm on my holy hill." Don't wait another day. Prophetic critique calls for the question; it is rightly impatient for change.

Pastoral comfort is different; it invites us to the long haul of patient endurance. When we witness what the psalmist calls "the turmoil of the nations" (65:7) — think of Ukraine today, and the decades that it will take for Russia to hope for any semblance of political normalcy, we still believe that God is "the hope of all the ends of the earth, and of the farthest seas" (65:5). Despite all that we know, and the appearance of outward events, we keep waiting for him to "hear our prayers, answer us with awesome deeds, and still the roaring of the seas." (65:2, 5, 7).

Agitation for change right now and quiet persistence for the far off future make awkward bedfellows. But we need both. Consider this example from one of my favorite movies. It's set in the civil rights era when there were criticisms all around that the movement was acting both too slowly and too quickly.

The historical drama The Butler (2013) by the director Lee Daniels tells the real life story of Eugene Allen. Forest Whitaker portrays the role of Cecil Gaines, a butler in the White House who served eight presidents from 1952 to 1986. Cecil and his wife Gloria (Oprah Winfrey) find themselves in the maelstrom of America's civil rights movement, albeit from an unusual vantage point.

Cecil's job description requires him to be "invisible" when he enters a room. He earned only 40% of what his white colleagues did. But with quiet dignity he did his job. He didn't rock the boat. He made the best of a bad situation. As a trusted butler, presidents asked his advice — where else could they have spoken to an ordinary black citizen? Late in Cecil's tenure, Reagan invited him to a state dinner, not as a lowly butler but as an honored guest. Then in 2008, he weeps to see Barack Obama elected president.

|

|

Fresco of the prophet Joel in Vienna's Altlerchenfelder church.

|

None of that was good enough for Cecil's elder son Louis, who joined the protest movements when he was in college. He thought his dad was a subservient sellout. Louis agitates for change now, he is impatient, then arrested and jailed. He becomes increasingly radicalized, and understandingly so.

Father and son become alienated from each other. In the end, though, they come to respect each other. Cecil marches with his son. Louis honors his father's service as a domestic servant.

Mary Pols notes how the movie is built on stereotypes. Cecil is the "Good Negro" of the 1950s, his son is the "angry black man" of the 1960s. But that's the conflict and tension that blacks faced in that era. King was criticized by both conservatives and radicals. There were no easy answers.

But this much is clear: the church and the world need both prophetic critique that demands change, and pastoral comfort on the long road of endurance. That's what the prophet Joel gives us.

Weekly Prayer

Seamus Heaney (1939–2013)

History says, Don't hope

On this side of the grave,

But then, once in a lifetime

The longed-for tidal wave

Of justice can rise up

And hope and history rhyme.

Seamus Heaney won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1995. Born in Northern Ireland, he was the oldest of nine children. Until his teenage years Heaney lived on his small family farm. Later, he lived in Belfast (1957–1972), and then taught at Berkeley, Harvard, and Oxford.

Dan Clendenin: dan@journeywithjesus

Image credits: (1) Wikipedia.org; (2) PICRYL Media; and (3) My Jewish Learning.