For Sunday June 3, 2016

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

1 Samuel 3:1-10, (11-20)

Psalm 139:1-6, 13-18

2 Corinthians 4:5-12

Mark 2:23-3:6

This past week, I had the privilege of attending a screening of Paper Lanterns, a documentary film about Shigeaki Mori, a survivor of the 1945 bombing of Hiroshima. Mori was eight years old when the bomb fell on his home city. In the film, he describes the mushroom cloud, and a darkness so total he could not see the fingers he held up to his face. He describes running through the ruined streets after the blast, tripping over the countless bodies that littered his path.

An amateur historian, Mori spent his early adulthood documenting the events of that terrible day. In the course of his research, he discovered the virtually unknown fact that twelve American POWs had died in the blast alongside the 140,000 Japanese victims — and that’s when his interest became an obsession. Though he didn’t speak a word of English, or have any personal connection to the United States, those twelve airmen broke Mori’s heart. At a time when he had every reason to fear and hate Americans, Mori saw the twelve young men, not as enemies, but as boys alone and forgotten in a doomed city, fellow victims deserving of the same dignity and compassion as their Japanese counterparts.

For the next forty-two years, Mr. Mori painstakingly researched those twelve men, learning their stories, seeking out their final resting places, tracking down their relatives in the U.S to offer solace and closure, and working to have their names registered at the Hiroshima Peace Museum. The research was slow, hard, frustrating, and costly. It involved combing through thousands of war-time drawings and documents, cold-calling people in the U.S in the hopes of finding the relatives of the deceased, wrestling through the red tape of Japanese bureaucracy, and working extra jobs on the side to fund a ceremonial plaque to honor the POWs. All this, while facing the bewilderment and contempt of his fellow countrymen, who couldn’t understand the compassion that drove him.

|

Mori and his wife were the guests of honor at the screening my son and I attended in San Francisco. He spoke briefly after the film, describing the challenges and joys of his work. Seventy-three years after the bomb fell, he still broke down weeping as he described the twelve soldiers who had captured his heart.

During my train ride home afterwards, I thought about Mori's story, and about this week’s Gospel reading, which raises questions similar to those posed by Paper Lanterns. What makes compassion possible? What makes it impossible? What truly counts as sacred, and how do we honor the sacred in the midst of desecration? When callousness, apathy, and fear threaten our hearts, how do we return to love?

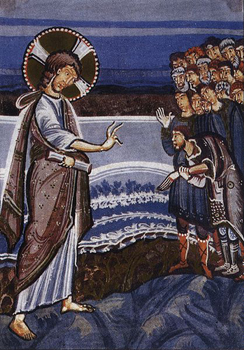

In this week’s lectionary, St. Mark describes a two-part confrontation between Jesus and the Pharisees. In part one, Jesus and his disciples are walking through a grain field on the Sabbath. When they get hungry, the disciples pluck a few heads of grain to munch on, Jesus doesn’t stop them, and the Pharisees pounce, asking Jesus why he’s allowing his followers to break the Sabbath. Jesus answers, “The sabbath was made for humankind, and not humankind for the sabbath; so the son of Man is lord even of the sabbath.”

In part two, Jesus enters the synagogue, and meets a man with a withered hand. Knowing that he’s being watched, Jesus asks the Pharisees whether it’s lawful to “do good or to do harm on the Sabbath, to save life or to kill.” But the Pharisees refuse to answer. Angered and grieved by their hardness of heart, Jesus heals the man with the withered hand. The story ends, predictably, with the Pharisees leaving the synagogue to plot against Jesus’s life.

|

Traditional (and disturbingly anti-Semitic) interpretations of this lection pit a rigid, legalistic Judaism against Jesus. But that reading (in addition to being harmful and inaccurate), lets us off the hook way too easily. The Pharisees in this story are not a stand-in for Judaism. They are a stand-in for all convictions, values, traditions, commitments, doctrines, absolutes, proclivities, preferences, and essentialisms — no matter how cherished, noble, or well-intentioned — that stand between us and compassion. In other words, the question this story asks is not, “What was wrong with 1st century Judaism?” but rather, “What have we — here and now — ossified at our peril? What mortal, broken thing have we deified instead of love? Who or what have we stopped seeing because our eyes have been blinded by our own best intentions?

What are we clinging to that is not God?

We do an injustice to the Pharisees if we write them off as bad people. They were good people — good people trying to preserve and protect those things — laws, rituals, traditions, habits — that mediated faith for them. Don’t we do exactly the same thing when we hold fast to our favorite worship practices, our cherished spiritual disciplines, and our beloved daily rituals? Don’t we just as readily decide what is sacred in our own lives, and then refuse to budge even when those things become obsolete and lifeless? The Pharisees were not wrong to uphold the Sabbath. They were absolutely right. But rightness is not love. Rightness is not compassion. Rightness will never get us to Jesus, the Lord of the Sabbath. Only compassion will do that.

|

This is an unnerving story. It’s a story about Jesus walking through the sacred fields in our lives, and plucking away what we hold dear. It’s a story about Jesus seeing people we’re too holy to notice, and healing people we’d just as well leave sick. It’s a story about a category-busting God who will not allow us to cling to anything less bold, daring, scary, exhilarating, or world-altering than love.

I imagine there are many people in Shigeaki Mori’s life who consider his work a waste of time at best, and a disloyal scandal at worst. Why would a man give up four decades of his life to honor twelve dead boys? Why would a Japanese survivor of the A-bomb care about providing closure to American families?

Why would anyone bring the business of a synagogue to a grinding halt on a Sabbath morning? Why would a man risk his own life to heal a stranger's withered hand?

Apparently, nothing is more sacred than compassion. The true spirit of the Sabbath — the spirit of God — is love. Love that feeds the hungry. Love that heals the sick. Love that sees and attends to the invisible. If we truly want to honor the Lord of the Sabbath, then we have to relativize all practices, loyalties, rituals, and commitments we hold dear — even the ones that feel the most “Christian.” There is only one absolute, and it is love.

Image credits: (1) Wikipedia.org; (2) Cast Your Net; and (3) Wikimedia.org.