For Sunday March 19, 2017

Third Sunday in Lent

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Exodus 17:1–7

Psalm 95

Romans 5:1–11

John 4:5–42

This past January I read the book Lethal Decisions: The Unnecessary Deaths of Women and Children from HIV/AIDS (2017) by Arthur Ammann. Art is a friend of mine, and a friend to JwJ. Every year since 2008 he's written an essay for us for World AIDS Day.

When I finished the book, it occurred to me that Art's life and work the last 50 years has been an extended incarnation of the gospel for this week about the Samaritan woman at the well — the longest discourse in all the gospels.

Early in 1982, as the Director of the Pediatric Immunology and Clinical Research Center at the University of California Medical Center in San Francisco, Art treated a woman who was a prostitute and intravenous drug user and three of her children. All four presented with unusual deficiencies in their immune systems that were aggravated by opportunistic infections that did not fit normal medical models of disease — the same patterns that he had been studying in gay men after Michael Gottlieb of UCLA identified AIDS as a new disease in a June 5, 1981 publication.

Art determined that the mother and all three children had contracted AIDS. This was a tragic diagnosis because the disease was at that time fatal. Equally devastating was a terrifying conclusion, hotly contested and very controversial at the time, that HIV-AIDS was not limited to adults. He had determined that the disease had passed from the mother to her children as an "acquired" and not an "inherited" disease. Art thus documented the first cases of AIDS transmission from mother to infant.

|

|

"My name, Amaretch, means 'the beautiful one'. I am the youngest of four children in my family. Today, I spent from 0300 to 1500 collecting the branches of eucalyptus trees which people use as firewood. I will sell this big bundle at the market for about $2. This will feed my family for a couple of days." Photo from BBC News.

|

On December 10, 1982, in a separate case of an infant who had received more than twenty blood transfusions from nineteen different donors, Art identified the first case of AIDS transmission by blood transfusion. This too was a tragic and controversial discovery that many people denied. The New England Journal of Medicine refused to publish his results, as did the British journal Lancet, until it relented and did publish the article on April 30, 1983. And not until 1985 was there a test approved for HIV for use in blood banks.

For the last fifty years, Art has been not just a leading expert at the center of the AIDS crisis, but also a tireless and vocal activist, especially for the women and children who have been impacted by HIV-AIDS, but also ignored, and especially women and children in the poorest parts of the poorest countries of the world (like war zones). His friend and colleague Gottlieb has called him "the conscience of the pediatric HIV epidemic." His book is a highly personal, deeply passionate, and even polemical history of the defining public health crisis of our generation.

The HIV epidemic resulted in some remarkable achievements by dedicated and brilliant scientists. Indeed, "all the scientific advances, tools, and knowledge necessary to begin the process of eradicating HIV in infants and children were in place by 1996" (272). ZDV, to take just one important example, was the first antiretroviral drug approved by the FDA, in record time, in 1987.

But consider Art's stark reminder — today "an estimated twenty-one million (59 percent of) HIV-infected individuals are still not on any treatment (UNAIDS 2016)" (277). If you are lucky enough to live in a wealthy country, you have access to state of the art drugs that now control HIV. Magic Johnson, for example, publicly announced that he had HIV way back in 1991. But in parts of Africa HIV is still a "hyper epidemic" (281), and treating children with the highly effective ZDV has been mired in needless controversy.

Art explains how this radical disparity came to pass. Looking back, he now sees "how difficult it can be, in spite of scientific evidence and personal tragedy, to move large and cumbersome institutions and the individuals working within them into action to protect the public from dangers." (26).

I was most surprised to read his two separate chapters on "denialism" within the medical-scientifc community. The many manifestations of bureaucratism loom large. Turf wars, research funding, government gridlock, drug development, issues of confidentiality and liability, gender based violence, self interest, conflicts of interest, and counterproductive treatment guidelines by WHO — all these combined to create a perfect storm of a catastrophic epidemic.

For Art, the story of his book is "one of hope and caution" (293). There have been both "extraordinary advances" and "tragic consequences" since 1981. For a long time now we have had the means to identify and treat every individual who is infected with HIV. He reminds us that there's no excuse not to do exactly that.

Jesus's encounter with the Samaritan woman at the well reminds us that the community he inaugurated calls for a people of inclusion not exclusion, dignity not denigration, empowerment rather than exploitation, and affirmation rather than marginalization.

His simple request for a drink of water provoked a dialogue with a marginalized woman that teaches us that God does not desire any human being to shrivel and die from a broken body or a parched soul. Rather, he longs to quench our deepest needs and desires with the "living water" of his Spirit.

As Jesus traveled from Judea to Galilee he stopped in the town of Sychar around noon time, tired and thirsty from the journey. He sat down by a well and asked a Samaritan woman for a drink of water.

That Jesus, a Jew, would talk to a Samaritan shocked the woman (4:9). That he would talk to a woman surprised his own disciples (4:27). In fact, through death or divorce, this woman had burned through five marriages and was then living with a man who was not her husband (4:18).

|

|

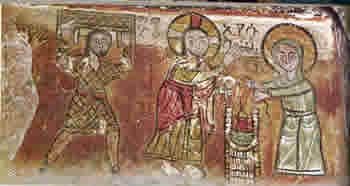

Jesus, the paralytic and the Samaritan woman at the well,

13th-century Ethiopia. |

When you connect the dots of her story, you realize that this woman epitomized the many ways that society marginalizes people. Jesus shattered all the taboos that held sway then (and now)—gender discrimination, ritual purity (sharing a drinking cup with a Samaritan), socio-economic poverty (any woman married five times was poor), religious hostility, and the moral stigma of serial marriages.

The Samaritan woman displayed spiritual thirst, candor about her many problems, and genuine insight about her real needs. She longed not only for literal water, but for the "living water" (4:11) that Jesus offered her, so much so that in her excitement she forgot her water jar when she returned to town (4:28). Spiritual nourishment suddenly became more important than material sustenance.

This marginalized woman made such a powerful impression upon Jesus and her own neighbors that John included an interesting eyewitness detail about Jesus's itinerary: upon the neighbors's request, "he stayed two days" in Sychar (4:40). The woman embraced Jesus as the Messiah, her witness converted many other fellow Samaritans in town (4:39), and she became the cause of the story's punch line: "We no longer believe just because of what you said; now we have heard for ourselves, and we really know that this man is the Savior of the world" (4:42).

As in so many gospel stories about God's alternative community, John 4 subverts and reverses conventional human wisdom and power relations. Jesus not only engaged a disreputable, ostracized, foreign woman; he cast her as the hero of the story, a symbol of life in his kingdom, and as an ardent witness to his universal lordship. She warns us of religiosity that turns a deaf ear to the disenfranchised.

Image credits: (1) BBC News and (2) Christopher Haas, Department of History, Villanova University.