For Sunday July 17, 2016

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Amos 8:1–12 or Genesis 18:1–10

Psalm 52 or Psalm 15

Colossians 1:15–28

Luke 10:38–42

Back on April 30, 2016, the church lost a modern day prophet when Father Daniel Berrigan died at the age of ninety-four. His niece Frida was with him when he died, and observed that Berrigan owned almost nothing — he still wore the same black shirt that he had at her wedding fifteen years earlier.

"Deeds, not things, made Father Berrigan one of the best-known Roman Catholic priests of the 20th century," observed Jim Dwyer in his May 8 reflection in the NYT. "He departed indifferently penniless from a world that often seems to keep score in gilded ink."

Berrigan was a Jesuit priest, poet (15 volumes), playwright, author of over fifty books, university professor, and peace activist. He spent a long life celebrating the good news of Jesus rather than the bad news of caesar.

I liken Berrigan to Amos in this week's reading. Both were troublers of the conscience who protested national delusions. Both epitomized how in the Bible "prophecy" is more about forth-telling God's word to society than about fore-telling the future.

Amos wrote 2,800 years ago, but he reads like today's newspaper. He lived during the reign of king Jeroboam II, who forged a political dynasty characterized by territorial expansion, aggressive militarism, and unprecedented national prosperity. The citizens of his day took pride in their religiosity, their history as God's favored people, their military conquests, their economic affluence, and their political security.

|

|

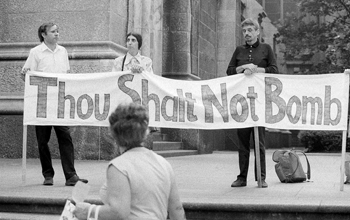

Vietnam protests.

|

Amos preached from the unpatriotic fringe. He was blue collar rather than blue blooded. He was a farmer from little Tekoa, about twelve miles southeast of Jerusalem and five miles south of Bethlehem.

The cultured elites despised Amos as a redneck. He was also an unwelcome outsider. Born in the southern kingdom of Judah, God called him to thunder a prophetic word to the northern kingdom of Israel.

Amos delivered a withering cultural critique. He describes how the rich trampled the poor. He says the affluent flaunted their expensive lotions, elaborate music, and vacation homes with beds of inlaid ivory. Fathers and sons abused the same temple prostitute. Corrupt judges sold justice to the highest bidder, predatory lenders exploited vulnerable families. And then religious leaders pronounced God's blessing on it all.

With Israel at the peak of its power, Amos preached a counter-intuitive and culturally subversive message. To the country's disbelief, he said that Israel was no different than the pagan nations with their war crimes. Before God they were equals.

He spoke to everyone, but especially to the nation's leaders — priests, judges, financiers, and state bureaucrats,"the notable men of the foremost nation" (6:1). In this week's reading Amos compared Israel to a basket of summer fruit that was not just ripe, but almost rotten (8:1).

I doubt that many people listened to Amos. Amaziah the priest defended Jeroboam the king, and ran Amos out of town — a classic example of the religious legitimation of the cultural status quo.

But Amos persevered. He announced the end of Israel's empire — an end that came swiftly. In 725 BC the Assyrian king Shalmaneser occupied Israel for three years, crushed the opposition holdouts, and then deported its population (2 Kings 17). In twenty-five short years Israel went from being a regional power under Jeroboam to a failed state under Shalmaneser.

Amidst the church's checkered history in relationship to power, politics, privilege, and wealth, Daniel Berrigan was a modern day Amos.

In 1968, he and eight other activists stole 378 draft files of men who were about to be sent to Vietnam, dumped them into two garbage cans, poured homemade napalm on them, and burned them in the parking lot of the Catonsville, Maryland, draft board.

As the photographers clicked away, Berrigan spoke: "Apologies, good friends, for the fracture of good order, the burning of paper instead of children… our hearts give us no rest for thinking of the Land of Burning Children."

|

|

Burning draft cards.

|

In 1980, he trespassed into General Electric's nuclear missile plant in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania, poured blood on some warhead nose cones, then hammered away — enacting the prophecy of Isaiah 2:4 about beating weapons of war into plowshares of peace.

For these and similar activities, he and his brother Philip spent time on the FBI's Ten Most Wanted list, not to mention significant time in prison.

Berrigan bore witness on a broad range of issues — racism (he marched in Selma), nuclear arms (he founded the Plowshares Movement), the death penalty, and most famously Vietnam (partnering with the likes of Howard Zinn and Thomas Merton). He also opposed what he called "the abortion mills."

In her memoir Things Seen and Unseen, Nora Gallagher recalls meeting Berrigan in the spring of 1986. When she asked how many times he had been jailed for the gospel, he responded, "Not enough." For his 80th birthday he remarked, “The day after I’m embalmed, that’s when I’ll give it up.”

But being a prophet isn't easy. Jim O'Grady once asked Berrigan "if it was tiring to constantly work on the fringes — of the Catholic church, of American politics, of polite discourse. He referred me to his old friend Dorothy Day, founder of the Catholic Worker, a volunteer community devoted to pacifism and serving the poor. 'She’s always thought of herself and her work as residing at the center of the Gospels,' Berrigan said. 'It was up to everyone else to move toward her.'"

Berrigan was also a realist. I was interested to read in his May 2 NYT obituary by Daniel Lewis about his deep discouragements.

Lewis writes, "While he was known for his wry wit, there was a darkness in much of what Father Berrigan wrote and said, the burden of which was that one had to keep trying to do the right thing regardless of the near certainty that it would make no difference. In the withering of the pacifist movement and the country’s general support for the fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan, he saw proof that it was folly to expect lasting results.

“This is the worst time of my long life,” Berrigan said in an interview with The Nation in 2008. “I have never had such meager expectations of the system.”

What made it bearable, he wrote elsewhere, was a disciplined, implicitly difficult belief in God as the key to sanity and survival."

Realism, futility, and discouragement were Berrigan's penultimate words rather than his final word.

|

|

Back to prison.

|

In his book No Gods But One (2009), a chapter-and-verse study of Deuteronomy, he wrote: "Nor is the fall the final judgment, as though we were bereft of all hope. No, there has occurred an intervention of God, for healing and reconciliation. An intervention named Jesus."

At the end of that book he calls us to "behave as though the truth were true."

Similarly, in his meditation on 1–2 Kings, The Kings and Their Gods (2008), he leaves us with this last word on his final page:

"One must urge (to his own soul first) a firm rebutting midrash; bring Christ to bear. Read the gospel closely, obediently. Welcome no enticements, no other claim on conscience. Mourn the preachers and priests whose silence and collusion signal plain revolt against the gospel. Enter the maelstrom, the wilderness; flee the claim that would possess your soul. Earn the blessing; pay up. Blessed — and lonely and powerless and intent on the Master — and, if must be, despised, scorned, locked up — blessed are the makers of peace."

NOTE: On Jim O'Grady, see The Nation: http://www.thenation.com/article/apologies-good-friends-for-the-fracture-of-good-order/

Image credits: (1) TheNation.com; (2) Wordpress.com; and (3) PopularResistance.org.