Comfort and Critique:

The Prophet Joel and a Plague of Locusts

For Sunday October 27, 2013

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Joel 2:23–32 or Jeremiah 14:7–10, 19–22

Psalm 65 or Psalm 84:1–7

2 Timothy 4:6–8, 16–18

Luke 18:9–14

Last spring some 30 billion cicadas that were born in 1996 emerged after seventeen years buried in the earth. It was like the locusts from this week's prophet Joel. Imagine what ancient people in an agrarian economy would have thought.

"What the locust swarm has left," writes Joel, "the great locusts have eaten. What a dreadful day! Before them the land is like the garden of Eden, behind them a desert waste."

The prophet Joel makes only a brief appearance in the biblical drama, and even then he's shrouded in obscurity. All that we know about him comes from his micro-prophecy, but that's next to nothing since the entire book takes only about five minutes to read.

|

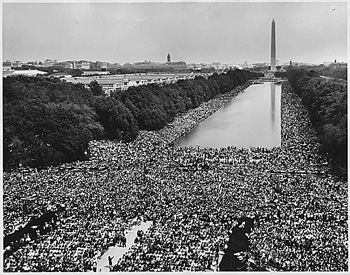

Fifty years ago, August 28, 1963/ |

His name means “Yahweh is God.” He says he's the son of Pethuel, but that's no help since we know nothing about his father. His several references to the temple lead some readers to think that Joel lived in Jerusalem, but that's only conjecture. And the time of his prophecy is murky, with scholars suggesting dates as early as 835 BC and as late as 200 BC.

Joel is a good example of the dual role that prophets played in the history of Israel.

First, Joel did more "forth-telling" about the present than "fore-telling" about the future. The business of the prophets was more prognosis than prediction. Prophets discerned with unusual clarity the significance of current events and the circumstances of God's people. Based upon their diagnosis, they spoke a word from God to provoke his people to change. By speaking God's word to our world, prophets call us to radical transformation.

Joel takes an everyday occurrence and interprets it as an act of God. "The locust plague that we are now experiencing," he says, "is an act of divine judgment calling us to repentance, renewal and redemption!"

He describes a locust plague that devastated the land, the economy and the people. Bark was stripped from trees, food vanished, seeds shriveled, granaries stood empty, cattle moaned from hunger and thirst, and streams evaporated into dry creek beds. With memories of the divine plagues of Moses, Joel interprets this natural disaster as a spiritual sign. It's a “day of the Lord," a phrase he uses six times. Israel, he says, should understand the plague as a divine invitation to turn to Yahweh for redemption.

But the prophets did more than "forth-tell" God's judgment. They cast a positive vision for the people of God. The rains will return. The vats will overflow with new wine. The threshing floor will be filled with grain.

"Your old men shall dream dreams," said Joel, "your young men will see visions." In addition to prophetic critique, the prophets offered pastoral comfort. They kept the dreams of God's people and his kingdom alive in times of disaster and discouragement.

|

Ordinary citizens demand radical change. |

Walter Brueggemann captures this dual role of the prophets nicely when he says that the prophets both criticized and energized. On the one hand, they disturbed the status quo. They questioned the reigning order of things. They viewed the normal state of affairs in a different light, and advocated a new way of seeing and living — personally, socially, spiritually, economically, politically, in short, in every dimension of life. The prophets afflicted the comfortable and the complacent.

But they also comforted the afflicted. They intended to “generate hope, affirm identity, and create a new future," says Brueggemann. They offered more than a negative critique; they were also about positive affirmation and encouragement. This is especially evident when Israel — God's elect! — was destroyed by the pagan nations of Assyria (722 BC) and Babylon (586 BC). How could that happen? Didn't it suggest the failure of God's plan, the abandonment of his people?

When Israel was in exile, feeling forgotten by Yahweh, the prophets consoled them with hope. “Do not be afraid," says Joel. If you've ever felt despair over a hopeless situation, the prophets have a word for you. Yes, they dished out the vinegar; but they also gave us honey for the heart.

Prophetic critique demands radical change. As in now. "Wake up!" writes Joel, "Weep! Wail! Blow the trumpet in Zion; sound the alarm on my holy hill." Don't wait another day. Prophetic critique calls for the question; it is rightly impatient for change.

Pastoral comfort is different; it invites us to patient endurance. When we witness what the psalmist calls "the turmoil of the nations" (65:7) — think Congo and Syria, Egypt and Iraq, we still believe that God is "the hope of all the ends of the earth, and of the farthest seas" (65:5). Despite all that we know, and the appearance of outward events, keep waiting for him to "hear our prayers, answer us with awesome deeds, and still the roaring of the seas." (65:2, 5, 7).

Agitation for change and quiet persistence make awkward bedfellows. But we need both. Consider these two examples.

This past August 28, the United States celebrated the 50th anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech and the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. The seminal moment in history reflected the endurance of blacks who had suffered 400 years of racism, and the agitation for change on the part of King and many thousands of ordinary citizens. The dream was kept alive by both critique and comfort.

Two weeks before that national celebration, the movie Lee Daniels' The Butler was released. Based on the real life of Eugene Allen, it tells the story of Cecil Gaines (Forest Whitaker), a butler in the White House who served eight presidents from 1952 to 1986. Cecil and his wife Gloria (Oprah Winfrey) find themselves in the maelstrom of America's civil rights movement, albeit from an unusual vantage point.

|

34 years in the White House, the real butler Eugene Allen. |

Cecil's job description requires him to be "invisible" when he enters a room. He earned only 40% of what his white colleagues did. But with quiet dignity he did his job. He didn't rock the boat, and made the best of a bad situation. As a trusted butler, presidents asked his advice — where else could they have spoken to an ordinary black citizen? Late in Cecil's tenure, Reagan invited him to a state dinner not as a lowly butler but as an honored guest. Then in 2008, he weeps to see Barack Obama elected president.

None of that was good enough for Cecil's son. He thought his dad was a subservient sellout. The son joins the civil rights movement, agitates for change, is arrested and jailed, and becomes increasingly radicalized.

Father and son become alienated from each other. In the end, they come to respect each other. Cecil marches with his son. His son honors his father's service as a domestic servant.

Mary Pols notes how the movie is built on stereotypes. Cecil is the "Good Negro" of the 1950s, his son is the "angry black man" of the 1960s. But that's the conflict and tension that blacks faced. King was criticized by both conservatives and radicals. There were no easy answers.

But this much is clear: the church and the world need both prophetic critique that demands change, and pastoral comfort on the long road of endurance.

Image credits: (1) Paul De Angelis Books; (2) tqn.com; and (3) celebnmusic247.com.