Picking Up the Broken Pieces

For Sunday April 14, 2013

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Acts 9:1–6, (7–20)

Psalm 30

Revelation 5:11–14

John 21:1–19

"O Lord my God, I called to you for help / and you healed me" (Psalm 30:2).

In a recent article about the movie Moonrise Kingdom (2012), the novelist Michael Chabon explores the film world of director Wes Anderson. In childhood, writes Chabon, we experience the world as unbelievably big and beautiful, but also as "irretrievably broken." Sooner or later, whether voluntarily or involuntarily, we all learn the bitter lessons of our broken world — "heartbreak, violence, failure, cowardice, duplicity, cruelty, and grief." Nor is that a complete list of lost innocence.

But beauty and brokenness mix and mingle. In the pangs of adolescence, we try to reconcile the two when they provoke "the ache of cosmic nostalgia, an intimation of vanished glory, a memory of the world unbroken." This second experience is as powerful as the first, and "the feeling haunts people all their lives."

In adulthood, people respond to the shattered fragments of life in different ways, says Chabon. Some people sit among the shards and just try to survive. Others break the broken pieces into smaller and smaller fragments. "And some people," he writes, "passing among the scattered pieces of that great overturned jigsaw puzzle, start to pick up a piece here, a piece there, with a vague yet irresistible notion that perhaps something might be done about putting the thing back together again."

|

The crucifixion of St. Peter by Caravaggio. |

This will always be an imperfect process. We can't see the lid of the jigsaw puzzle with its perfect picture of the completed whole. Some pieces will always be missing. "The most we can hope to accomplish with our handful of salvaged bits is to build a little world of our own." Chabon compares these recreated worlds to a scale model of the broken original. They're partial approximations and imperfect replicas. But even in their imperfections they can be "faithful maps" of the "beautiful and broken world." And that's what Wes Anderson has done in his movies.

It's also what Peter had to do in this week's gospel. He had to pick up the pieces of his broken life. Peter was eating breakfast on the shores of the Sea of Galilee with the resurrected Jesus. Dirty, wet and tired from fishing all night and catching nothing, he huddled around a "fire of burning coals." As he extended the palms of his hands to warm himself before the crackling fire, Jesus asked Peter not once, but three times, "Peter, do you really love me?" Three times Peter responded, "Yes, Lord, you know that I love you."

John writes that "Peter was hurt" by Jesus's query. The triple question evoked a deeply painful memory of his triple denial. The last time he stood around a campfire just a few days earlier, he denied three times that he even knew Jesus. But now Jesus reinstates Peter three times with the words, "Feed my sheep," and despite his bitter past he went on to become the movement's leader.

Similarly, this week's reading from Acts describes Paul's Damascus road conversion. Before his conversion, Paul "breathed out murderous threats" and aggressively sought to imprison believers. After his conversion, the greatest persecutor of the church became its greatest propagator, eventually traveling over 10,000 miles to spread the good news of God's love.

But the memories of Paul's past always cast a dark shadow. Even as an old man Paul remembered his sordid past to the younger Timothy with remarkable candor: "I was once a blasphemer and a persecutor and a violent man." He considered himself "the worst of sinners." But as with Peter's restoration, after his conversion Paul also transcended his past, however imperfectly: "forgetting what is behind and straining toward what is ahead, I press on toward the goal to win the prize for which God has called me heavenward."

|

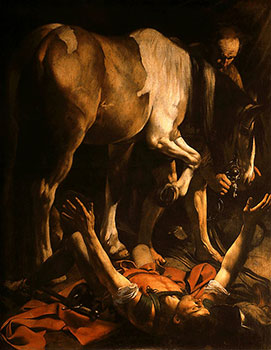

The conversion of St. Paul by Caravaggio. |

But notice the caveats that both Peter and Paul received about the imperfect nature of restoration and conversion. They are foretastes of a more perfect future, only down payments on our continuing debt to mortality.

To Peter: "When you were younger you dressed yourself and went where you wanted; but when you are old you will stretch out your hands, and someone else will dress you and lead you where you do not want to go." Henri Nouwen once used this verse as a shorthand for Christian maturity — to go where you'd rather not go.

To Paul: "This man is my chosen instrument to carry my name before the Gentiles and their kings and before the people of Israel. I will show him how much he must suffer for my name." It is only through many trials and temptations, said Paul, that we inherit the kingdom of God.

And as we know, according to tradition, both men were martyred.

No matter how imperfect our replicas and scale models of God's once and future Original, we should never lose hope. "Should we fall, we should not despair and so estrange ourselves from the Lord’s love," encouraged St. Peter of Damaskos (12th century); "let us always be ready to make a new start. If you fall, rise up. If you fall again, rise up again."

We get up again, Frederick Buechner suggests, because as Christians we are "people who have been delivered just enough to know that there’s more where that came from, and whose experience of that little deliverance that has already happened inside themselves and whose faith in the deliverance still to happen is what sees them through the night."

Note: See Michael Chabon, The Film Worlds of Wes Anderson, NYRB (March 7, 2013), p. 23.

Image credits: (1) Wikipedia.org and (2) State University of New York at Albany.