The Edge of the World

A guest essay by Sara Miles (http://www.saramiles.net/). Sara is Director of Ministry at St. Gregory of Nyssa Episcopal Church in San Francisco (http://www.saintgregorys.org/) and the author of Take This Bread and Jesus Freak: Feeding Healing Raising the Dead.

For Sunday April 1, 2012

Palm Sunday or Passion Sunday, the Sixth Sunday in Lent

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Isaiah 50:4–9a

Psalm 31:9–16

Philippians 2:5–11

Mark 14:1–15:47

This week the grace of the Holy Spirit calls out to us. It’s Palm Sunday, Passion Sunday, the end of Lent and the beginning of Holy Week. For the last forty days, as we sang way back on Ash Wednesday, the church has been “sailing across the great sea of the fast.” And this week we’re about to — thrillingly, scarily — sail right off the edge of the world.

|

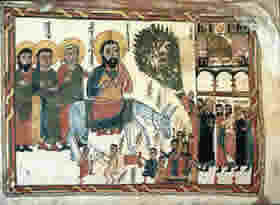

Jesus's Triumphal Entry, Medieval Syriac manuscript. |

Working in a church during this season is really weird. The Gospel narrative is moving faster and faster. We’re getting caught up in this dramatic story: the growing crowds, the escalating miracles, Jesus’ increasingly reckless self-revelation. We’re swimming in long, long passages of the most intense Scripture: living water, spit and mud turned into vision, the wild shout of COME OUT to a dead man, a flood of tears and perfume, the whole sense of gathering doom and meaning and danger and glory.

And at the same time I'm ordering paper cups and plastic forks for Easter. I'm answering email until nine at night. I'm getting absorbed in my own self-important busy-ness, juggling spreadsheets and phone calls and visits from the copier repair guy, and trying to figure out how the morning crew of volunteers can get those gigantic palm branches cut, trimmed, and hung without provoking another argument with the evening crew, who thought they had booked the space for rehearsal and setting up the folding chairs. My throat hurts, I'm irritable from lack of sleep, I'm eating stale tortilla chips because I can’t stop for lunch, and I don’t have time to pray, much less listen to one more person with a question. I am officially in the weeds, the Holy Week weeds.

|

The Condemnation of Christ and the Denial of Saint Peter, early fifth century, British Museum, London. |

But it doesn’t matter. This week the grace of the Holy Spirit calls us. And grace has brought us to the edge of the known world. We’re entering God’s time now: time out of time, kairos time, and nothing we do or don’t do can stop it.

And so, on Palm Sunday, I take off my watch for a week. I invite you to take off your watch too, or do whatever it takes for you to enter God’s time. To walk with Jesus, all the way through Holy Week.

In this week's epistle, St. Paul quotes the early Christian hymn, the Kenosis, or emptying, hymn, that describes how Jesus gives himself totally away in love. Jesus is one with the Father from before the beginning: one God, at the center of all life. But as a human being, for the sake of all human beings, Jesus keeps moving further and further toward the edge. He turns his back on claims to power, humbles himself to serve the undeserving, empties himself so we can experience God's fullness, and dies so we can live. St. Paul is writing to urge us, the faithful, to do the same thing. “Make your mind the same mind that was in Christ Jesus,” he says, so that you too will “walk in a manner worthy of the Gospel."

It’s a manner that seems perilous at best. Over the course of the great narrative we hear during Lent, Jesus has given up family, reputation, home, safety. He has become a scandal in the eyes of the temple authorities and illegal in the eyes of the state.

|

Mosaic of Christ before Pilate, Basilica of Saint Apollinare Nuovo, 6th century. |

This Sunday, as if he’s suddenly coming to his senses, Jesus enters Jerusalem, hailed by crowds who want to make him into the triumphal king who will save them from Rome. But Jesus doesn’t care. He is already walking away from our shouts of hosanna. He’s moving toward the meal he most longs for, the last one, when he’ll kneel down like a servant to wash his friends’ feet. He’s walking toward our angry shouts of “Crucify him!” and toward our betrayals, as one by one we abandon him to torture and death; he is walking toward the edge of the world.

And none of it can stop him. He jumps off the edge, on to the cross.

And into God’s time. Life, eternal. The life we are living today.

Cucifixion icon, Sinai, 8th century. |

Which means, in a pretty unsettling way, Holy Week can’t be about a story that took place in the past, or a mere remembrance, or a historical re-enactment. It’s about the kind of life Jesus makes possible for all of us right now.

That life demands a different mind than the one I generally use. My own mind wants to shout hosannas in a happy crowd waving palms, and later on be able to blame that other crowd, the Jews, for all the bad stuff that happens. My own mind wants to claim Jesus as my friend and me as his personal favorite and pretend I won’t betray him, later, like his other friends. I want to act as if I’m somehow separate from all the other suffering, sinful souls Jesus pours himself out for: disciples and executioners, cheering and jeering crowds; each one of you.

So it’s really hard for me to walk with Jesus in a manner worthy of the Gospel. Sure, I want forgiveness; but I don’t necessarily want to admit how violent my impulses can be, how capable I am of yelling “crucify.” Sure, I want new life, but I don’t want to sit abandoned in a garden, be humiliated and hurt and killed, to get there. I want to hang on to my own power, and save myself, rather than empty myself like Jesus. I know Palm Sunday’s exciting, but I also have a feeling it’s going to get pretty dark over the next week, before it’s time for Easter.

Except — except that we’re on God’s time now. And it turns out I don’t have to jump off the edge of the world alone, because Jesus already has. His abiding love is everywhere. The good news is that there’s nothing left for me to do through my own anxious efforts at self-improvement. There’s nothing left for any of us to do. God is always moving all humanity closer to God, with the endless love of our friend and savior Jesus lighting the way for us, from the cross.

|

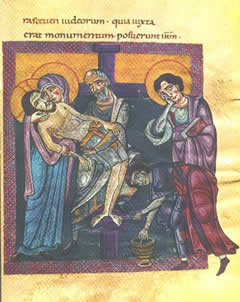

Descent from the Cross, 12th century, parchment, Nonantola (Modena, Italy), Abbey`s Library. |

Back when I first started going to church, a dozen years ago, I went around in a daze, as a friend told me later, “like a deer caught in the headlights.” I’d been blindsided by Jesus, who I didn’t believe in, but who, to my shock, had shown up anyway, quite alive, in a piece of bread. I used to come to church and sit during the early service, waiting for more bread, and halfway listening to the Scriptures or whatever the preacher was saying. I’d stare out the window, gazing at the tangle of green ivy and nasturtiums beyond in a spaced-out way. One day I noticed the window frames. They seemed to have a very peculiar construction. “Oh,” I thought, “Look at that. It’s a…cross! You can see a cross over everything… You can see everything through the cross… Wow, there’s a cross over the whole world!”

I was unprepared, and undeserving, and stupid. But there is a cross over the whole world, and you can see everything through it. See the crowds, see the disciples, see Jesus: riding the donkey into Jerusalem, eating supper with friends, stumbling up the hill. And if you let your mind be made in the mind of Christ Jesus, you will stay beside him the whole way, because you see where all this is going.

It is going toward love. It is going toward life. And it cannot be stopped.

Image credits: (1) Christopher Haas, Department of History, Villanova University; (2) Museum of Antiquities, University of Saskatchewan; (3) Robert W. Brown, Dept. of History, University of North Carolina Pembroke; (4) Jugoslav Ocokoljić; and (5) Chiesa Cattolico di Torino.