Between Resistance and Submission:

A Question from

Dietrich Bonhoeffer

For Sunday September 4, 2011

Lectionary

Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Exodus 12:1–14 or Ezekiel 33:7–11

Psalm 149 or Psalm 119:33–40

Romans 13:8–14

Matthew 18:15–20

I recently read Dietrich Bonhoeffer's "Letters and Papers From Prison" (Princeton, 2011) by Martin Marty. Bonhoeffer (1906–1945) was a Lutheran pastor who was imprisoned for his resistance to the Nazis, including a plot to assassinate Hitler. After two years in prison, and just three weeks before the war ended, he was hanged at dawn on April 9, 1945.

Marty begins with the book's unusual birth as a collection of random letters, sermons, poems, and reflections written by Bonhoeffer from his ten-foot by seven-foot prison cell 92 of Tegel prison. They include censored letters to his fiance Maria von Wedemeyer and to his confidant, former student, and eventual biographer Eberhard Bethge. Some uncensored papers were smuggled out of prison with the help of sympathetic Nazi guards. Still others were later discovered buried in gardens or hidden in roof beams by family and friends. Many papers were lost, and Bethge himself burned some before he was arrested in order to protect the identity of people.

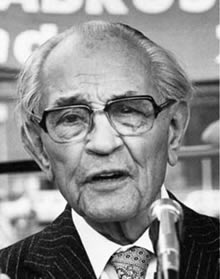

|

Dietrich Bonhoeffer. |

In a labor of love and pains-taking scholarship, after Bonhoeffer's death Bethge tracked down, collected, organized and edited the papers into a book which today we know as Letters and Papers from Prison. It's been published in numerous editions and translated into twenty languages. The new critical and definitive edition of 2010 by Fortress Press runs to 800 pages.

Bonhoeffer could have stayed in the United States at Union Theological Seminary in New York, where he was a visiting professor, and was pressured to do so. But he faced a moral quandary. He wrote to Reinhold Niebuhr: "I have come to the conclusion that I made a mistake in coming to America. I must live through this difficult period in our national history with the people of Germany… Christians in Germany will have to face the terrible alternative of either willing the defeat of their nation in order that Christian civilization may survive or willing the victory of their nation and thereby destroying civilization. I know which of these alternatives I must choose but I cannot make that choice from security."

The original 1951 German edition has the provocative title Resistance and Submission. It comes from a question Bonhoeffer asked in prison: "I have often wondered here where we are to draw the line between necessary resistance to 'fate,' and equally necessary submission." What does resisting fate and evil powers mean? What does submitting to God's providence look like? Should a Christian will harm to her nation for the sake of the gospel? Can one wish for national victory if it destroys the church or other nations?

Scripture affirms that Yahweh intervenes not only in the lives of individuals but in the affairs of nations. Sometimes he judges nations with "disaster upon disaster" (Jeremiah 4:12, 15, 20; Exodus 32:14). Exodus 12 describes the institution of the Jewish feast of Passover that commemorates Israel's liberation from 430 years of bondage to slavery in Egypt. Liberation from oppression is always worthy of celebration by the saints.

Exodus also suggests that emancipation for Israel meant subjugation for Egypt. Today we might say that the oppressed became the new oppressor, except that in this narrative revenge was the act of God himself. In something like divine infanticide, God slays the first-born of every Egyptian, from the highest in Pharaoh's house to the lowliest prisoner languishing in a dank dungeon, and even including the firstborn of Egyptian livestock. To punctuate his point, the writer adds: "there was loud wailing in Egypt, for there was not a house without someone dead" (Exodus 12:30). In a departing act of humiliation, the Hebrews plundered their Egyptian oppressors.

Or consider the schizophrenic zeal in Psalm 149. The first half of the psalm describes dancing, singing, music, and praise of God. But in the second half of the psalm tambourines and harps give way to swords and shackles:

May the praise of God be in their mouths

and a double-edged sword in their hands,

to inflict vengeance on the nations

and punishment on the peoples,

to bind their kings with fetters,

their nobles with shackles of iron,

to carry out the sentence written against them.

This is the glory of all his saints (Psalm 149:6–9).

I love the anemic understatement in the New Oxford Annotated Study Bible (1991) footnote to Psalm 149: "The dance was evidently of war-like character." Oh, yes it was.

Perhaps the enemies of the psalmist somehow deserved their humiliation. Maybe there's a mysterious divine providence at work in the rise and fall of nations, or maybe you could read this as the normal but tragic rhetoric of ancient military conquest. Whoever laughed at the notion of poetry as a political act? For the psalmist it was a short step from pious praise to religious rage. He glorifies the religiously righteous who brandish the Scriptures in one hand and a sword in the other.

Some people defend a theology of a warrior God who slays his enemies (see Peter Leithart, 1&2 Kings, 2006). I prefer the view of Daniel Berrigan (The Kings and Their Gods, 2008) who suggests that texts like Psalm 149 reflect how the writer saw himself and his nation, and how he (wrongly) thought that God saw his "enemies." I'm uncomfortable with linking divine judgment and national disaster. It's one thing to affirm that God acts in the history of nations, but quite another to claim to know how, when, where, or why.

|

Martin Niemoeller. |

We shouldn't wish divine judgment on any person or nation, even if it appears good and necessary. We should wish them God's shalom. When you imagine that God hates all the people you hate, then you can be sure you've created him in your own image. No, said the German pastor Martin Niemoeller, who was also imprisoned by Hitler for eight years, "It took me a long time to learn that God is not the enemy of my enemies; he's not even the enemy of his own enemies."

What we should wish for every person and nation comes from this week's epistle. Paul borrows a passage from the Hebrew Old Testament to instruct the earliest followers of Jesus: "Love your neighbor as yourself" (Romans 13:9 = Leviticus 19:18). The only debt we should carry, he says, is the never-ending debt to "love your fellow human being." Loving your neighbor fulfills any and every other divine command, for genuine love "does no harm to its neighbor." We're to love not only our neighbor but even our enemy (Matt. 5:43–48).

As a matter of principle, Quaker pacifism takes this to its logical extreme. Last week I read Quaker Writings; An Anthology, 1650-1920 (2010), which documents Quaker pacifism back to the year 1661: "All bloody principles and practices, we, as to our own particulars, do utterly deny, with all outward wars and strife and fightings with outward weapons, for any end or under any pretence whatsoever; this is our testimony to the whole world." We need this reminder when we see how easily divine judgment becomes an excuse for human vengeance.

As a matter of practice, though, it's scary to think what our world would be like if brave people like Bonhoeffer didn't risk guilt to resist evil. He never justified his actions. In his Ethics he wrote: "when a man takes guilt upon himself in responsibility, he imputes his guilt to himself and no one else. He answers for it… Before other men he is justified by dire necessity; before himself he is acquitted by his conscience, but before God he hopes only for grace."

And so Bonhoeffer's question resonates today. How do we resist the evil forces of fate while submitting to the good providence of God?

For Further Reflection

Martin Niemoeller (1892–1984)

First They Came

First they came for the Communists,

- but I was not a communist so I did not speak out.

Then they came for the Socialists and the Trade Unionists,

- but I was neither, so I did not speak out.

Then they came for the Jews,

- but I was not a Jew so I did not speak out.

And when they came for me, there was no one left to speak out for me.

This poem is ascribed to the German pastor Martin Niemoeller (1892–1984), who protested Hitler's anti-semite measures in person to the fuehrer, was eventually arrested, and then imprisoned for eight years at Sachsenhausen and Dachau (1937–1945). The poem describes the passivity of German intellectuals as the Nazi's purged group after group of targeted people. The poem comes in many slightly different versions, and its exact origin is the subject of debate.

Image credits: (1) Wikipedia.org and (2) Martin-Niemöller-Schule Wiesbaden.