Dreams of a Christmas Credo

For Sunday December 19, 2010

Fourth Sunday of Advent

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Isaiah 7:10–16

Psalm 80:1–7, 17–19

Romans 1:1–7

Matthew 1:18–25

"Come and save us," the psalmist implores God (80:2).

And in a call-and-response separated by 1000 years, the gospel proclaims, "He will save his people" (Matthew 1:21). That's the Christmas good news, that the birth of a son signals the redemption of the cosmos, or as Paul put it, that "God was in Christ reconciling the world to himself" (2 Cor. 5:19).

|

Angel. |

Matthew's story of the birth and infancy of Jesus includes five dreams. Four of those dreams were by Joseph, and the fifth one by the pagan magi. In his first dream (1:20), an angel spoke to Joseph in words that echo down to us today: "Don't be afraid." Joseph was caught between the public disgrace of a pregnancy out of wedlock and the pain of a private divorce of Mary. He "did what the angel of the Lord commanded him," and endured the public scorn.

In Joseph's second dream (2:13) God warned him that king Herod intended to kill Jesus, and instructed the young family to flee to Egypt for safety. This is the same Herod whom the pagan magi were warned to avoid in the fifth dream (2:12). The political ironies in the flight to Egypt are remarkable. The infant Son of God fled as a displaced refugee to a foreign country, Egypt, Israel's sworn and symbolic enemy that had oppressed the Hebrews for 430 years (Exodus 12:40). The place where Pharaoh had unleashed an infanticide against the Israelite children (Exodus 1:6–22) became a refuge for Jesus.

In his third dream a few years later (2:19), God instructed Joseph that Herod had died, so the young peripatetic family returned to Judea in Israel. But after learning that Herod's son Archelaus reigned in place of his father Herod, Joseph feared for their lives. In a fourth dream (2:22) God instructed him to move his family yet again, this time to Nazareth of Galilee.

Four of these five dreams warn of king Herod's plans to kill the baby Jesus. Why does the birth announcement of Jesus include such overt and ominous political overtones? A clash between a Roman governor and a peasant baby? In addition to the four gospels, there's a fifth birth narrative in the New Testament. I've never heard it read at Christmas, but it illuminates the other four and the confrontation between Jesus and Herod.

|

A Lady Expecting. |

This other birth narrative takes place in heaven rather than on earth. In contrast to Luke's bucolic imagery of a baby in a barn, this fifth birth announcement explodes with apocalyptic imagery from a cosmic perspective. In Revelation we read about a woman crying out in labor pains as she gives birth to "a son, a male child, who will rule all the nations with an iron scepter." An enormous red dragon stands in front of her spread legs, "so that he might devour the child the moment it was born" (Revelation 12:1–13:1). The baby in the barn would be the ruler of the nations, and therein resides the clash of two kings.

For the earliest believers, Rome was that beastly dragon, the incarnation not of divine love but of human tyranny. What had Rome done to deserve Revelation's outrageous imagery and opprobrium? Didn't Rome give us highways and aqueducts, a language and architecture, the rule of law and the Pax Romana? True, but they also martyred Christians for three hundred years.

Even more disturbing than that were the claims made by the caesars of that day. Roman emperors assumed divine titles like “son of God”, “lord” and even “god.” Consider this inscription from Asia Minor from about 9 BC that describes caesar Augustus:

The most divine Caesar. . . we should consider equal to the Beginning of all things. . . Whereas the Providence which has regulated our whole existence. . . has brought our life to the climax of perfection in giving to us the emperor Augustus. . . who being sent to us as a Savior, has put an end to war. . . The birthday of the god Augustus has been for the whole world the beginning of good news [the Greek word here is euangellion, “gospel” or "good news"].

Both Joseph's earthly dreams about Herod and John's cosmic imagery of a savage dragon provoke the question: who is the ultimate lord and king? Whose birth, in the words of that ancient inscription, is "the gospel for the whole world?" Is the Roman caesar lord and god or is the baby of Bethlehem? Is the "good news" that of political power or of love incarnate?

|

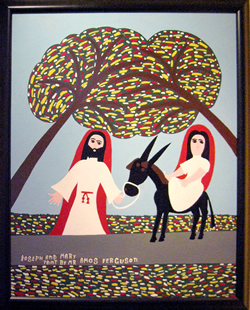

Joseph and Mary. |

Revelation 1:5 confesses that Jesus is “the ruler of the kings of the earth.” Herod was right to feel threatened. As Marcus Borg writes, Rome “designates all domination systems organized around power, wealth, seduction, intimidation, and violence. In whatever historical form it takes, ancient or modern, empire is the opposite of the kingdom of God as disclosed in Jesus.”

"Come and save us." Political power, whether in ancient Rome or modern America (or whatever other country you might like to substitute here), is only one of many false gods that offer a gospel of salvation. Consumerism promises fulfillment but alienates us from our true selves. Propaganda, regardless of its content, tries to integrate us into its own narrative. The alternative "gods" to which we bow down are almost endless — sex without love, wealth without generosity, work with no sense of call, and knowledge without wisdom.

The renegade priest and peace activist Daniel Berrigan (born 1921) repudiates our many false gods in his poem "Credo."

I can only tell you what I believe; I believe:

I cannot be saved by foreign policies.

I cannot be saved by the sexual revolution.

I cannot be saved by the gross national product.

I cannot be saved by nuclear deterrents.

I cannot be saved by aldermen, priests, artists,

plumbers, city planners, social engineers

nor by the Vatican,

nor by the World Buddhist Association

nor by Hitler, nor by Joan of Arc,

nor by angels and archangels,

nor by powers and dominions,

I can be saved only by Jesus Christ.

This is what Paul calls "the gospel of God" in the epistle for this week, a gospel that deconstructs every other false hope. And it's hard not to read a note of irony when he directs his invitation "to all who live in Rome" (Romans 1:7).

Image credits: (1) Amos Ferguson;