Oblivious to the Obvious:

Be a Healer, Not a Hater

For Sunday February 14, 2010

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

Exodus 34:29–35

Psalm 99

2 Corinthians 3:12–4:2

Luke 9:28–36 (37–43)

One day you will look back

And you'll see

Where you were held.

How? By this love.

While you could stand there

You could move on this moment,

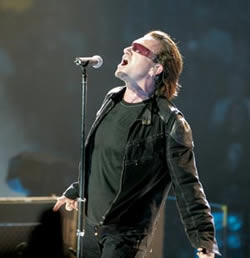

Follow this feeling. — U2 lyrics, "Mysterious Ways"

My daughter called me from college last weekend. That's always a treat, but this time she was in tears.

Another high school classmate had stepped in front of a train on the tracks near our house. Brian was the fifth suicide at our high school in nine months. My daughter remembered him from her math class as a fun kid with a big family. Brian's brave mother confirmed in the newspapers that he had struggled with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia.

Another human being in need of healing love. Like each one of us.

And had I ever heard of Fred Phelps, she asked in a quivery voice?

No, I hadn't.

|

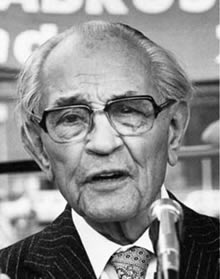

Fred Phelps with protesters. |

Well, she sobbed, Fred Phelps (born 1929) was some nut job pastor with a web site called godhatesfags.com. He and his hate mongers had targeted our high school for a protest on Friday. In fact, Phelps's web site claims to have conducted "41,226 peaceful demonstrations (to date) opposing the fag lifestyle of soul-damning, nation-destroying filth."

Fred Phelps is badly wrong. He's also a liar (see below).

No, God doesn't hate gays.

Yes, God loves my nephew Sam and my niece Jesse. He loves my neighbor's daughter, my former pastor's son, and my current pastor's brother. God loves my sister-in-law's brother, my daughter's high school friends, and Dick Cheney's daughter Mary. And he definitely loves the transgender child of friends.

Yes, God is love, and in him there is no darkness at all. He loves all the world and every person in it. Astonishingly, God loves haters like Fred Phelps.

Luke's gospel for this week describes how Jesus called twelve men to be his closest confidants. He invested them with power and authority, but to do what? To drive out demons and to enlighten the darkness. To cure diseases. To preach the subversive love of God, and to heal the sick. "So they set out and went from village to village," writes Luke, "preaching the gospel and healing people everywhere."

|

Bono. |

For two thousand years Jesus has invited people to be healers and not haters. Healing love is the mark of a disciple. "By this," said Jesus, "all people will know that you are my disciples, that you love one another." Jesus invites us to bring the outsider inside. To include the excluded. He tells us to befriend the broken, heal the hurting, and embrace the alien. Jesus calls us to care and to cure, not to condemn, which according to one word history comes from the prefix com + damnare "to harm, damage."

This is a tall order for each of us. The first disciples stumbled and bumbled, failed and floundered. In the gospel for this week a distraught father screamed in desperation from a large crowd for Jesus to heal his son — "he's my only child, and I begged your disciples to heal him but they could not." And then, when Jesus rebuked his closest followers and explained his mission once again, "they did not understand what this meant."

They couldn't heal. They didn't understand.

There's a sad history of misunderstanding and failure among the apostles, most notably by Peter. He denied that he would ever deny Jesus, but then did so three times. To his credit, he "wept bitterly" after doing so. Peter had a transforming vision that convinced him that God played no favorites and did not hate Gentiles. Yes, God loved even the Gentiles, and Peter proclaimed so. But years later he separated himself from these "impure" and "unclean" Gentiles when he caved in to zealots of ritual purity.

Whereas a besieged Jesus welcomed the bedraggled crowds and healed them, the twelve disciples urged him to "send them away." When someone outside of the Jesus movement tried to heal a person, John boasted with misplaced pride, "Master, we saw a man driving out demons in your name and we tried to stop him, because he is not one of us." Toward the end of his life, when Jesus passed through a Samaritan village and they refused even basic hospitality to him, James and John exploded: "Lord, do you want us to call down fire from heaven to destroy them?"

Jesus defined our love of God by our love of neighbor. You cannot separate the two. To have one is to have the other, and to neglect one is to lose them both. The necessary connection between claiming to love God and demonstrating that we love our fellow human beings became so embedded in the early Christian traditions that all three Gospels contain a version of the story about this "greatest command" (Matthew 22:34–46 = Mark 12:28–31 = Luke 10:27).

|

Martin Niemoller. |

The command to love our neighbor is repeated almost verbatim by Paul (Romans 13:8–9, Galatians 5:14), who says that it's "the only thing that matters," by James (James 2:8), and most memorably by John: "If anyone says, 'I love God,' yet hates his brother, he is a liar. For anyone who does not love his brother, whom he has seen, cannot love God, whom he has not seen. And he has given us this command: Whoever loves God must also love his brother" (1 John 4:20–21).

In the epistle for this week Paul describes how a "veil" over our hearts can obscure the obvious. "Our minds can be made dull," writes Paul, even to a simple truth like God deeply loves every person without qualification or exception. Like Fred Phelps and even Jesus's closest followers, we can become purveyors of death, darkness and condemnation.

We shouldn't be smug or sanctimonious. The pressures of cultural conformity are enormous. Our only hope is for what Paul calls a dramatic transformation by the Spirit of God in which "the veil is taken away." Paul says that through a "metamorphosis" by the Spirit of God we can become "icons" of Jesus himself. As we contemplate God's healing love we're transformed by that love, and in turn reflect and refract it to each and every person we meet.

For further reflection

Martin Niemoller (1892–1984)

First They Came

First they came for the Communists,

- but I was not a communist so I did not speak out.

Then they came for the Socialists and the Trade Unionists,

- but I was neither, so I did not speak out.

Then they came for the Jews,

- but I was not a Jew so I did not speak out.

And when they came for me, there was no one left to speak out for me.

This poem is ascribed to the German pastor Martin Niemoeller (1892–1984), who protested Hitler's anti-semite measures in person to the fuehrer, was eventually arrested, and then imprisoned for eight years at Sachsenhausen and Dachau (1937–1945). He once confessed, "It took me a long time to learn that God is not the enemy of my enemies. He is not even the enemy of his enemies." The poem describes the passivity of German intellectuals as the Nazis purged group after group of targeted people. The poem comes in many slightly different versions, and its exact origin is the subject of debate.

Image credits: (1) Paul Wilkinson blog; (2) Examiner.com; and (3) Reinaldo Azevedo blog.