|

Palm Sunday or Passion Sunday: "He's No Friend of Caesar!"

Sixth Sunday in Lent 2009

For April 5, 2009

Lectionary

Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year B)

Psalm 118:1–2, 19–29

Mark 11:1–11

John 12:12–16

Macedonian icon of Jesus's Triumphal Entry (13th century). |

For three years Jesus criss-crossed the villages of Galilee teaching in synagogues, preaching the good news of God’s kingdom, and healing the sick. Thousands of people trampled each other just to get a look at him (Luke 12:1). Some people responded positively, for reasons that were both good and bad. Many others responded with rejection, resistance, and unbelief. To say that at the end of those three years he was a controversial figure would be a gross understatement.

Toward the end of those three years Jesus “resolutely set his face toward Jerusalem.” When he entered that city for the last time, knowing full well that betrayal, persecution and death awaited him, it’s easy to imagine that he was greeted by his largest and most boisterous crowd. His so-called “triumphal entry” on what we call Palm Sunday triggered the beginning of the end for Jesus.

What began on Sunday with a religious procession ended Friday morning with a public display of state terror. Excited children waving palm branches were quickly forgotten when violent mobs shouted death chants. The adulation of the crowds evaporated into abandonment by his closest friends.

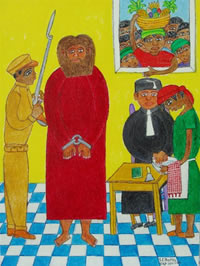

|

Jesus before Pilate, Seymour E. Bottex, Haiti. |

By Good Friday, Jesus's disciples argued among themselves about who was the greatest, Judas betrayed him, Peter denied knowing him, all his disciples fled (except for the women), and Rome employed all the brutal means at its disposal to crush an insurgent movement — rendition, interrogation, torture, mockery, humiliation, and then a sadistic execution designed as a "calculated social deterrent" (Borg) to any other trouble makers who might challenge imperial authority.

Jesus's "triumphal entry" into the clogged streets of Jerusalem on Good Friday was a deeply ironic, highly symbolic, and deliberately provocative act. It was an enacted parable or street theater that dramatized his subversive mission and message. He didn't ride a donkey because he was too tired to walk or because he wanted a good view of the crowds. The Oxford scholar George Caird characterized Jesus's triumphal entry as more of a "planned political demonstration" than the religious celebration that we sentimentalize today.

Because the Roman state always made a show of force during the Jewish Passover when pilgrims thronged to Jerusalem to celebrate their political liberation from Egypt centuries earlier, Borg and Crossan imagine not one but two political processions entering Jerusalem that Friday morning in the spring of AD 30. In a bold parody of imperial politics, king Jesus descended the Mount of Olives into Jerusalem from the east in fulfillment of Zechariah's ancient prophecy: "Look, your king is coming to you, gentle and riding on a donkey, on a colt, the foal of a donkey" (Matthew 21:5 = Zechariah 9:9). From the west, the Roman governor Pilate entered Jerusalem with all the pomp of state power. Pilate's brigades showcased Rome's military might, power and glory. Jesus's triumphal entry, by stark contrast, was an anti-imperial and anti-triumphal "counter-procession" of peasants that proclaimed an alternate and subversive community that for three years he had called "the kingdom of God."

|

The Condemnation of Christ and the Denial of Saint Peter, early fifth century, British Museum. |

Jesus was executed for three reasons, says Luke: "We found this fellow subverting the nation, opposing payment of taxes to Caesar, and saying that He Himself is Christ, a King" (Luke 23:1–2). In John's gospel the angry mob warned Pilate, "If you let this man go, you are no friend of Caesar. Anyone who claims to be a king opposes Caesar" (John 19:12).

People today argue about who's "subverting our nation." A friend in Florida forwarded me an email that blamed Muslims in America for our problems. Others attack evangelicals as "Christian fascists." For a long time conservatives have taken aim at "secular humanists" and liberal Democrats. On his nationally televised program Jerry Falwell blamed the wickedness of pagans, abortionists, feminists, gays, lesbians, the ACLU, and People for the American Way for the 9-11 disaster, which he construed as God's judgment. Pat Robertson, a guest on the show, nodded in agreement, “well, I totally concur.” Rush Limbaugh, the greed of corporate executives and the sleaze of Hollywood movies all make easy targets.

|

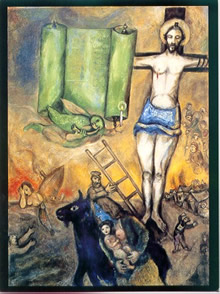

Marc Chagall, "Yellow Crucifixion" (1943). |

But I’ve never heard anyone say what the Gospels say — blaming Jesus, that Jesus is the one who's "subverting our nation." But that was the allegation that sent Jesus to Golgotha.

What were Jesus and his first followers subverting? We know that the earliest believers were called "atheists" because they refused to participate in Rome's cult of imperial worship, and a "third race" that distinguished itself from the "first race" (Greeks and Romans) and the "second race" (Jews). The question deserves a lifetime of reflection, but a simple summary by Borg and Crossan (The Last Week; A Day-by-Day Account of Jesus's Final Week in Jerusalem) also makes a good beginning.

Jesus's alternate reign and rule, they argue, subverted major aspects of the way most societies in history have been organized. Whether ancient or modern, most societies have normalized a status quo of political oppression that marginalizes ordinary people, economic exploitation whereby the rich take advantage of the poor, and religious legitimation that insists that "God wants things this way." It's easy to think of other components of the cultural status quo that Jesus might also subvert, like ethnic stereotypes, media propaganda, gender roles, consumerism, and our degradation of planet earth.

|

Burial of Christ, Cathédrale d'Auch (France). |

On Palm Sunday, Jesus invites us to join his subversive counter-procession into all the world. But he calls us not to just any subversion, subversion for its own sake, or to some new and improved political agenda. Rather, Christian subversion takes as its model Jesus himself, "who, being in very nature God, did not consider equality with God something to be grasped, but made himself nothing, taking the very nature of a servant, being made in human likeness. And being found in appearance as a man, he humbled himself and became obedient to death — even death on a cross."

Image credits: (1) Open Society Institute of Macedonia; (2) Arte del Pueblo: Latin American & European Arts; (3) The Museum of Antiquities Collection, University of Saskatchewan; (4) Jeremy D. Popkin, Universtiy of Kentucky; and (5) Futur Quantique.