|

Celebrating the Saints:

All Saints Day

For Sunday November 2, 2008

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Joshua 3:7–17 or Micah 3:5–12

Psalm 107:1–7, 33–37 or Psalm 43

1 Thessalonians 2:9–13

Matthew 23:1–12

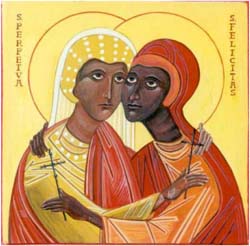

Eastern Orthodox icon of the saints. |

This week Christians observe All Saints Day on November 1, the day after Halloween. But they do so in different ways and for different reasons.

During its first three hundred years, the church suffered widespread persecutions, and so Christians celebrated their leaders, heroes and especially martyrs of the faith. Literature of the fourth century indicates that churches honored saints in their liturgies. Churches were named after saints, relics were collected and honored, the dates of their death were commemorated, and special communion services were held at their tombs. Churches were even built on their tombs.

The church eventually concluded that all believers who had died, and not just famous saints, should rightly be commemorated. For Catholics, All Saints Day took final form in the year 835 when Pope Gregory IV ordered the Feast of All Saints to be universally observed on November 1. Eastern Orthodox churches observe All Saints Day on the first Sunday after Pentecost. Protestants get positively nervous about celebrating the saints.

Protestants cringe at the superstitions that developed across the centuries. In Luther's Wittenberg, for example, prince Frederick the Wise had an extraordinary cache of sacred relics. An illustrated catalog by Lucas Cranach (1509) listed 5,005 articles — a tooth from Jerome, three pieces of Mary's cloak, a piece of gold from the three Wise Men, a piece of bread from the Last Supper, a strand from Jesus's beard, and so on. By 1520, says Roland Bainton, the collection of holy bones had grown to 19,013.

These vulgar distortions of the Gospel made Luther's blood boil: "What lies there are about relics! One claims to have a feather from the wing of the angel Gabriel, and the Bishop of Mainz has a twig from Moses' burning bush. And how does it happen that eighteen apostles are buried in Germany when Christ had only twelve?" Most galling of all, the church displayed these relics on All Saints Day, and for the proper financial contribution, the pope would reduce your time in purgatory up to 1,902,202 years and 270 days. Of course, we rightly repudiate such flagrant abuses.

Protestants also get nervous about blurring the boundary between honoring the saints and worshiping them, praying to them for protection, kissing icons of them, and treating them as mediators to God or even co-redeemers with Christ. Protestants emphasize a distinction that both Catholics and Orthodox acknowledge, at least in theory if not in popular practice — Christians honor or venerate (duleia) the saints, but we don't worship them (latreia). Worship is due to God alone.

Protestants also disagree about the definition of a "saint." Catholics use the word “saint” in a narrow and technical sense. Saints are Christians whose lives have been characterized by extraordinary holiness, heroic virtue, and the performance of miracles. Only the Pope may canonize a believer as a “saint.”

|

Catholic depiction of saints. |

The first step to sainthood is called “beatification,” for which there are three criteria — theological soundness, extreme holiness, and the performance of two miracles. If the Pope verifies all of that, the person is then honored as “Blessed” so-n-so. But to be canonized as a "saint," the believer must also be credited with two additional miracles. Whereas the "beatified" receive only local recognition, the "saints" are venerated worldwide. Whereas believers are permitted to venerate the beatified, veneration of a "saint" is mandated. Finally, the pope's act of canonizing a saint is declared to be an infallible act, meaning Catholics can be assured that the saint is worthy to be venerated and imitated, and that the saint can intercede for them.

All this is way too complicated for Protestants. It's also discouraging — I'll never be a saint! When Pope John Paul II canonized Latin America's first indigenous saint, Juan Diego, a Nahuatl Indian who converted to Catholicism in the early 16th-century, I resonated with the remarks of a retired bus driver named Bernardo Gomez. He complained that canonizing Diego actually distanced ordinary believers from him, for they had loved him as a humble, peasant person just like them, not someone famous and highly exalted to sainthood. “Juan Diego was an ordinary man chosen by the Virgin to be her messenger,” said Gomez. “That's what he did.”

Protestants resonate with Gomez. They maintain that all believers, not just a famous few superstars, are "called to be saints" (Romans 1:7). We prefer the plural, “saints,” which includes all Christians (as in the Apostles' Creed, “I believe in the communion of saints”), as opposed to the singular, “saint,” which suggests an exalted status. Paul, for example, addressed his letters to "all the saints" in Rome, Ephesus, and Philippi (Ephesians 1:15, Philippians 1:1). In this Protestant view, I'm a saint not because of my heroic deeds, my virtuous character, or my performance of miracles, but because God calls me to Himself in a lifelong pilgrimage.

But Protestants shouldn't over react and throw out the baby with the bath water. We shouldn't dismiss a practice just because it's abused. Protestants could do a better job of honoring the role that the saints can play in our Christian lives, especially for us who in stressing the personal nature of salvation often slide into individualistic, privatistic, and even narcissistic patterns of discipleship. We should see ourselves in the greater, communal identity of all God's people. There's a social and corporate dimension to our journey with Jesus that should include the saints.

When I think about the saints, whether the especially holy like Mother Teresa or the egregiously fallen like Jimmy Swaggart, I'm reminded that I have choices to make in my Christian life, and that my choices matter. These choices have consequences for my spiritual welfare. Believers are told to imitate not only Christ but the saints. Paul urged his readers to imitate his way of life several times (1 Corinthians 4:16). Hebrews 6:12 commands us to “imitate those who through faith and patience inherit what has been promised” (cf. Hebrews 13:7). Other saints, by the choices they've made, have “shipwrecked their faith” (1 Timothy 1:19), and I do well to consider them too.

|

Saints Perpetua and Felicitas, third century women martyrs. |

In addition to imitation there is consolation. The saints console me that I'm not alone. Rather, I am surrounded by “a great cloud of witnesses” (Hebrews 12:1), who cheer me on to “run with endurance the race that is set before me.” Wherever I find myself on the Christian pilgrimage, in joy or despair, faith or doubt, sin or grace, millions of believers have gone before me. Some have failed miserably, others have triumphed gloriously. But at the end of the race, whether they ran well or poorly, they found ultimate rest in God's grace that knows no boundaries and love which knows no limits.

So, celebrate the saints. We need both the Catholic and Protestant ideas of sainthood. The former challenges and inspires us; the latter offers consolation and encouragement for all the normal struggles of life. Find a fellow saint and share your own journey with Jesus, encouraging one another to love and good works (1 Thessalonians 5:11, Hebrews 10:24)

Image credits: (1) Arimethea.co.uk; (2) CatholicGreetings.org; and (3) ExecutedToday.com.