|

Aaron and The Gods of Gold

For Sunday October 12, 2008

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Exodus 32:1–14 or Isaiah 25:1–9

Psalm 106:1–6, 19–23 or Psalm 23

Philippians 4:1–9

Matthew 22:1–14

|

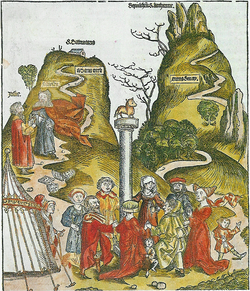

Dance Around the Golden Calf, Emil Nolde, 1910. |

"Come, make us gods who will go before us" (Exodus 32:1).

Before Moses ever descended Mount Sinai with the Ten Commandments, the second of which reads "you shall not make for yourself an idol" (Exodus 20:4), the Hebrews grew impatient. They hectored Aaron for a golden calf. They built an altar so they could bow down to their "gods of gold" (32:31). In this ancient story, so evocative with contemporary applications, the people worshipped a golden god, sacrificed to it, "indulged in revelry" (32:6), and proclaimed national celebrations.

Idols lure us with powerful illusions and misplaced hopes. They make seductive promises. These false gods come in all sizes and shapes. They promise much but deliver little. We can idolize almost anything — career, race, gender, sex, wealth, age, and especially nation. Our personal gods are so petty and pathetic that they would be laughable if they weren't so insidious and corrosive. The robust health of the advertising industry testifies to the power of our puny "household gods."

Personal idols are child's play compared to national idols. National idolatries are more global than personal, more public than private, and more institutional than individual. They wreck far more violence upon humanity than our household gods. The most vicious of these is the War God. C. Wright Mills used a suggestive description when he spoke of a "military metaphysic," by which he meant a way of construing every national aspiration or international problem in distinctly military terms.1 In the last hundred years, at least 200 million people, mainly civilians, have been sacrificed to the War Gods.

|

'Dans om het gouden kalf' 1976; by Fri Heil; in Koningsplein Arnhem, ('Sin of the golden calf'). |

The idol of war, writes Chris Hedges, "is the most common and destructive form of idolatry, one that has left most religious institutions morally bankrupt." Orthodox, evangelicals, Catholics, and liberal Christians have all invoked God to justify warfare's "slaughterhouse and orgy of destruction" (Bacevich) as a means to secure and expand national self-interests. A Catholic priest in Guatemala blesses weapons and soldiers, Pat Robertson calls for the assassination of a head of state, religious liberals romanticize the Marxist Sandinista government, and Serbian Orthodox priests countenance ethnic cleansing.2 Without the wholehearted complicity of conservative evangelicalism, American militarism would have been "inconceivable," says Bacevich, a tragic irony when you consider that the most "Christian" nation on earth did far less to repudiate the War Gods than many ostensibly "secular" nations.

In his book The New American Militarism (2005), Bacevich desacralizes our idolatrous infatuation with military might, and in a way that avoids the partisan cant of both the left and the right. Idolizing militarism, Bacevich insists, is far more complex, broader and deeper than scape-goating either political party, accusing people of malicious intent or dishonorable motives, demonizing ideological fanatics as conspirators, or replacing a given administration. Not merely the state or the government, but society at large, worships the War Gods.

Our military idolatry, says Bacevich, is now so comprehensive and beguiling that it "pervades our national consciousness and perverts our national policies." We have normalized war, romanticized military life that formally was deemed degrading and inhuman, measured our national greatness in terms of military superiority, and harbored naive expectations about how waging war, long considered a tragic last resort that signaled failure, can further our national self-interests.

In 2005 the United States accounted for 48% of the entire world's military spending — which is to say that our one country nearly spent more on the military than the rest of the world combined. Our Department of Defense says that America deploys 254,788 military personnel (double that number if you include dependents) to at least 725 military bases in 153 countries. Our own country is home to 969 separate bases in all fifty states. By these budgetary metrics, the United States sacrifices its people and treasure to the War Gods like no nation on earth.

|

The Worship of the Golden Calf by Filippino Lippi (1457–1504). |

In his book Overthrow, Stephen Kinzer examines the fourteen times in the last century that the United States has toppled foreign governments. Specialists will debate the nuances of outright coups, covert activities, mixed motives, and historical consequences, but by giving us the big picture, Kinzer reminds us that America's geopolitics is hardly benign or altruistic. "No nation in modern history," he writes, "has done this so often, in so many places so far from its own shores."

In 1795, James Madison warned that "of all the enemies of public liberty, war is perhaps the most to be dreaded, because it comprises and develops the germ of every other".3 The text from Isaiah for this week says that to understand God in terms of narrow nationalism secured by military violence is to create an idol in your own image. Three times he identifies "ruthlessness" as a besetting national sin (25:3,4,5). Rather, Isaiah writes, God longs to prepare a rich banquet for "all people," to eliminate everything that separates "all nations," wipe away the tears of "all faces," and, in stark contrast to our idolatry of militarism, He longs to "swallow up death forever."

For further reflection:

* For further reading see David Livingstone Smith, The Most Dangerous Animal; Human Nature and the Origins of War (New York: St. Martin's Press, 2007), 263pp.

* Find people who are both Christian believers and veterans of active duty with whom to discuss military idolatry.

* Can you think of examples of our culture's idolatry of war?

* Meditate on the poem by Wilfred Owen (1893–1918), Dulce et Decorum Est. By some accounts this is the most famous war poem of World War I. DULCE ET DECORUM EST - these are the first words of a Latin saying (taken from an ode by Horace) that end the poem: Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori - it is sweet and right to die for your country. After graphic descriptions of his experiences in war, Owen's poem calls this "The Big Lie."

[1] Cited by Andrew Bacevich, The New American Militarism; How Americans Are Seduced By War (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), p. 2.

[2] Chris Hedges, Losing Moses on the Freeway (New York: Free Press, 2005), p. 50.

[3] Bacevich, p. 7.

Image credits: (1) The Artchive; (2) Flickr.com; and (3) Wikimedia.org.