Like Lambs Among Wolves:

Gospel Reflections on the Temptations of Violence

A guest essay by Sara Miles, author of Take This Bread: A Radical Conversion (2007). Sara is the director of ministries at St. Gregory of Nyssa Episcopal Church in San Francisco, where she founded The Food Pantry.

For Sunday July 8, 2007

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year C)

2 Kings 5:1–14 or Isaiah 66:10–14

Psalm 30 or Psalm 66:1–9

Galatians 6:1–6, 7–16

Luke 10:1–11, 16–20

|

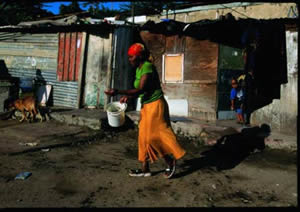

Alexandra, South Africa. |

Long before I was a Christian, I was a reporter, and I specialized in writing about military affairs—specifically, revolutionary wars and the ways they played out on the ground in the Third World.

Writing about and living in such wars absorbed me totally. I used to feel ashamed that I found so much joy in the midst of the violence and dirt and ugliness. Some of it, I think, was the simple adrenaline thrill of danger, and a guilty but real happiness about coming out alive. Plenty of it was romance. But another piece was the intensity of connection that collective experience, even terrible collective experience, provides: the powerful intimacy of sharing life and death together.

What I learned in those moments of danger and sorrow in many countries informs my faith now. It was a feeling of total community with others, experienced through the common fact of our mortal bodies. We all had bodies that could suffer and be killed; we all had hearts that could stop beating in an instant. This solidarity had nothing to do with nationality, nothing to do with worldly power. In war, I looked at other, different people and saw them, face to face: and in seeing them felt a we.

Never was that feeling stronger than when ordinary people took me into their homes and offered me food and drink and rest. In El Salvador, a priest gave me cookies; in the Philippines, a peasant woman gave me fish. The impulse to share hospitality is basic and ancient, and it’s no wonder all the old stories teach that what you give to a stranger, you give to God. Over and over, despite the poverty of the places I visited, despite the grief my nation had brought upon theirs, strangers welcomed me. And in the middle of war, I found peace.

In South Africa in the early 1990s, apartheid was in its final throes: the white state, with its security forces and death squads, was unleashing violence upon black people at an unprecedented rate. I had been in the country for about a week when a friend from the African National Congress, Mzwanele, took me to cover what the government officially called “unrest.” I rented a cruddy little car, and stuck a notebook in my pocket; Mzwanele took nothing but a bandana to wipe the sweat off his face.

We set off. It was ten in the morning in Alexandra township, just outside of Johannesburg, and the sun was already scorching, beating down on the rutted road. A dozen people had been killed overnight, and more disappeared or were arrested, and everyone was terrified.

Mzwanele and I drove very slowly through the homemade barricades that were mushrooming at intersections. We got out of the car at one point and stood next to a boy with an open wound on his arm. His chest was heaving up and down from running, as he faced a semi-circle of gigantic police tanks. There were acrid blasts of tear gas and smoke from burning tires; I could see a line of armored personnel carriers descending a hill towards us. People scattered, running down alleys and dodging out of sight of the army. There was a rush of voices and a sound of breaking glass somewhere close by. And then the shooting started.

I stumbled. A grandmotherly woman in a flowered skirt standing at the door of her shack beckoned urgently to us. “Come here,” she said. Mzwanele deposited me inside, saying he’d be back.

|

South African police at Alexandra

Township in 1985. |

See, I am sending you out like lambs among wolves (Luke 10:3). I’ve seldom been as visibly an outsider as I was in Alexandra that day: a foreigner, the wrong color, someone whose very presence meant danger for the people around me. The woman calmly motioned me to sit down at her kitchen table, under a print of Jesus, a calendar, a broken clock. She took some spoons and mugs off a shelf and said, thoughtfully, “I think we should kill a lot of white policemen. Maybe fifteen, twenty white policemen. And then they’ll have to stop this business.”

Then the woman smiled at me, pouring the hot dark tea from a banged-up kettle. She stirred sweetened condensed milk into my cup, humming under her breath. “Here, my dear, drink it,” she said.

I had no idea that what was settling upon me in that moment, as I sipped my tea and traced my finger over the pattern in the linoleum, was the peace of God.

But I knew the woman’s offer of peace was stronger than anything I was afraid of. The gunfire and the shouting were still there, outside, but in that kitchen some other power prevailed.

Remain in the same house, eating and drinking whatever they provide. The kingdom of God is very near (Luke 10:7, 9).

In the late afternoon, Mzwanele came back for me, and we walked over into the township stadium, where ten thousand unarmed people were gathering for a march, despite police orders.

The stadium was ringed by tanks with gun mounts on their turrets, riot-police vans, armored cars; policemen with pistols and army troops with automatic rifles; white soldiers with tear-gas grenade launchers and black police with shotguns; plainclothes cops with radios; sharpshooters, dog handlers and spies.

There remains on Earth––have you noticed?—the very real threat of powers and principalities. There remains the temptation to see ourselves as special, others as less than human; to kill in the name of the nation and tribe. Satan has fallen like lightning, but the armies of empire are not destroyed. And still the kingdom of God is very near.

A helicopter hung overhead. The police bullhorn bleated at us to disperse. “Watch,” said Mzwanele, and through the haze of smoke I saw a ten-year old girl, her dress whipping around her knees, dancing in front of the tanks.

Out of nowhere, out of everywhere, people began to sing in harmony and clap, and with a deep collective sigh the whole crowd began to move forward singing out of the stadium, dancing toward Calvary, the place of the skulls.

The kingdom of God is very near. Entering that kingdom is as simple as welcoming a stranger into your house, and saying, “Peace be with you.” It is as difficult as welcoming a stranger into your house, and saying, “Peace be with you.” The air is full of tear gas, and the streets of this world are full of broken children, and the Kingdom of God is very near.

Iraq. |

In South Africa fifteen years ago, in Baghdad this afternoon, in a hundred slums tonight where armies and gangs rage, the Son of Man is going up to be glorified.

He is walking with the disciples directly into the line of sharpshooters, leaving behind violence and the temptations of power. She is contemplating revenge, rejecting it, offering a stranger a cup of tea as she prepares to be killed. He is refusing to strike the prisoner; she is bandaging the burnt child. He is turning his back on the empire, the nation, the flag, the tribe.

There is violence all around us. But Christ is here, and we are singing.

Kingdom come.

Alleluia.

(© 2007 Sara Miles)

For further reflection:

* Where and when have you felt like a lamb among wolves?

* How have you experienced the temptations of violence?

* Why is "entering the kingdom" both simple and difficult?

* Cf. Chris Hedges, War is a Force That Gives Us Meaning.