Absolute Moral Clarity? The Case of Terri Schiavo

For Sunday April 10, 2005

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Acts 2:14a,36–41

Psalm 116:1–4, 12–19

1 Peter 1:17–23

Luke 24:13–35

|

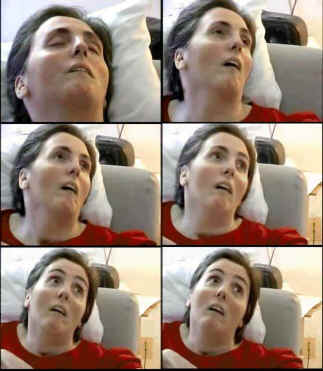

Terri Schiavo |

On February 25, 1990 Terri Schiavo collapsed at her home in Florida from cardiac arrest, perhaps from a potassium imbalance due to her bulimic condition, and suffered severe neurological damage when her brain was deprived of oxygen for five minutes. After fifteen long years of rancorous litigation and accusations, on March 18, 2005, her feeding tube was removed (for the third time) to allow her to die. This, insisted her husband Michael, was her specific wish. The courts concurred, while her parents disagreed. Terri finally died on March 31, 2005 at the age of 41.

From many different quarters, Terri's case generated extraordinary bluster and bombast, pandering and posturing, with opportunistic rivals arguing in favor of a single, right decision. Not all moral choices are difficult, but for at least ten reasons I consider her case to be one of complex moral murkiness rather than of absolute ethical clarity. Consider the tangled thicket of issues.

* The relationship between federal and state jurisdictions, and their intervention in individual rights.

* The separation between the executive, judicial, and legislative powers of government.

* The role of media and public opinion: most Americans (59%) agreed with the decision to remove Terri's feeding tube, most (69%) said that if they were in her place they would want their feeding tube removed, and even more said they thought that it was wrong for Congress and the President to intervene (70-75%).1

* What is the proper role of religion in government and politics, or of Terri's Catholic faith?

* Many groups manipulated Terri's case to further their own, broader political agendas like the right-to-life (stem cell research, abortion) and right-to-die (physician-assisted suicide, death with dignity) movements. Movements on both the right and left have co-opted Terri as their "poster child."

* A deeply estranged and acrimonious family, with charges of greed, spousal abuse, adultery, misdiagnosis, and interference. Of some two dozen court decisions, including six appeals to the Supreme Court, all but one ruled in favor of the husband Michael.

* Complexities of medical diagnosis: in a persistent vegetative state, which the courts ruled described Terri's condition, a person is "awake but not aware." There is a loss of cognitive neurological functions like thinking and speaking, but a retention of non-cognitive functions like respiration, blood circulation, a normal sleep cycle, and reflexive actions like gripping a finger or eye movement. Still, one of the most debated topics in philosophy and neuroscience right now, and one that sells a ton of books, is the very definition of "consciousness."

* Well-founded fears of lawsuits: in 1992 Michael sued and won over a million dollars, although now almost all this money has been used for legal and medical bills.

* Terri's unwritten and therefore contested medical directive about what to do in just such a situation. If you have not stipulated your own wishes through a living will or advance medical directive, state laws vary widely. In 31 states the spouse decides, in 2 the physician and next of kin, in another 2 a consensus of "interested persons," in 3 parents and spouse have equal status, and in 12 states no priority is specified.2

* Sincere, fervent, and differing moral convictions of good people.

It is futile to expect absolute moral clarity in an ethical choice as complex as this one. There is, in fact, a tradition in ethics called "non-conflicting absolutism," which argues that right is right, wrong is wrong, and that moral obligations like truth-telling and life-saving never conflict. Terri's case is one reason why I do not subscribe to that position.

|

Terri Schiavo |

The Psalmist for this week offers Christians two important reminders. First, and most important, "our God is full of compassion" (Psalm 116:5). He pictures a tender God who hears our cries, who inclines his ear to our voice, who meets us in our troubles and sorrows, and saves us in moments of great need. This does not mean that God simplifies complex moral decisions, or absolves us of the human responsibility to seek wise and good choices in tragic circumstances, but it does mean that we can make those choices with confidence that he empathizes with our morally murky condition.

Second, from a biological viewpoint, death is our natural and inevitable end. Some medical treatments tread a thin line between needlessly prolonging death and genuinely extending life. The apostle Paul also referred to death as our greatest "enemy" and so we rightly protest and resist dying. But Christians who have just celebrated the Easter story believe that Jesus vanquished death. The Psalmist for this week even writes, "precious in the sight of the Lord is the death of his saints" (Psalm 116:15). Believers rightly resist death, consider it an enemy, and grieve its arrival, but we also maintain staunch hope that the biological end of life is not our personal end.

What we hope for in a case like Terri Schiavo's is not absolute moral clarity, but confidence to choose knowing that God cares for our confusion and that in Christ he conquered death. What we rightly pray for is not crystalline clarity but what Paul called discernment or insight that we might choose what is best (Philippians 1:9–10). In this regard I have always appreciated the wise words of ethicist Lewis Smedes:

Discernment is the insight, for instance, into the difference between a living person and a mechanically sustained biological organ, between a person who is going to die and a person who is actually dying, between a living person and a breathing corpse. And discernment is the power to sense what is really at stake when we have to make a decision about somebody else's life or death.

The problem is that even when we have discernment we still see things through a glass darkly. We don't have perfect discernment. And we don't have it with the same acuteness one day that we have it on another day. And we don't always know whether we have it or not—especially when someone else sees the same thing differently than the way we see it. So when we pray for discernment, we do not expect to get an infallible 20-20 sense of things going on around us.

Discernment is not a kind of divine intuition that gives us infallible clairvoyance. It is a heightened power to look at and listen to what is going on in front of our eyes and see it for what it is, in all its dimensions.3

|

Terri Schiavo before the incident. |

Christians thus understandably "discern" the Terri Schiavo case differently. I did not think it was wrong to allow her to die by removing her feeding tube. Others posed a provocative question that gave me pause: if her parents were ready, willing, and able to assume full care for Terri, if her own wishes were truly unclear, and if her husband had long since moved on with a new partner and children, what harm was there in letting Terri live?

My wife and I have debated the case, and we agree on something very simple that would have almost certainly prevented Terri's tragic and morally complex case: we will sign advance medical directives asap. Neither of us wants to live or die like Terri, or burden the other with the tragic choice like the one that her husband Michael faced. One perceptive television commentator put it this way: he based his own opinion about Terri Schiavo on how he hoped others would treat him if he was in her condition.

[1] Time Magazine (April 4, 2005), pp. 26-27.

[2] Time, ibid.

[3] Lewis Smedes, Reformed Journal 37.7 (July 1987).