Book Notes

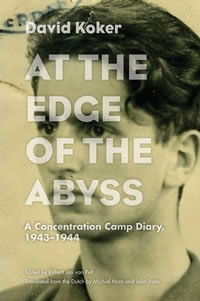

David Koker, At the Edge of the Abyss; A Concentration Camp Diary, 1943–1944, edited by Robert Jan van Pelt, translated from the Dutch by Michiel Horn and John Irons (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2012), 397pp.

David Koker, At the Edge of the Abyss; A Concentration Camp Diary, 1943–1944, edited by Robert Jan van Pelt, translated from the Dutch by Michiel Horn and John Irons (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2012), 397pp.

"Thursday, February 11 [1943]: Picked up between eleven and twelve p.m. One police officer decent but anxious, and one unpleasant. I heard them coming."

With that entry David Koker (1921–1945), a young Dutch Jew, began a book-length diary of his life and death in the Vught concentration camp. His last entry was a year later, on February 8, 1944. Vught was a "regular" labor camp, not an extermination camp, although the inmates constantly dreaded its transformation into a "transit" camp and the regular mass transports to Auschwitz. Installments of the diary, written in exercise books, were smuggled out by civilian workers in the camp. They eventually found their way to David's brother Max, who survived five concentration camps, then to Dutch state archives, where they came to the attention of David's high school teacher Robert Jan van Pelt. He published the original Dutch diary in 1977; it was an immediate classic and publishing sensation.

Koker's diary is especially important in the Holocaust literature for a number of reasons. Make no mistake, this is a trip to the inner circle of Dante's hell, but, having said that, the diary is an example of what Hannah Arendt called "the banality of evil." In Koker's own words, "the dreadful thing about the camp is that it so treacherously imitates real life and happiness." There are bad people who are good, like compassionate SS guards who are "just soldiers" and not anti-Semites, who turn a blind eye to broken curfews and love-making, and who instead of arresting Jews give them gifts, and even crack jokes when the numbers for roll call don't add up. We also encounter good people who are bad, like inmates who connive, steal, betray, run a camp brothel, and quarrel over who got more butter. There is art, music, love and beauty, but also horrible degradation, hunger, and evil.

With his own privileged status Koker survived much longer than many. I was surprised to read how food parcels and mail from family and friends were a regular part of camp life. He had better jobs, and even had responsibility for deciding who would be transported to the extermination camps. There were choices, personal preferences, and tradeoffs. "When you've played at being providence for an evening, you go to bed with a moral hangover and great doubts." He's well aware of his own complicity and ambition, and even admits how much he likes to "polish the apple."

At times Koker becomes insensitive to the inhumanity of it all and reproaches himself for how easily everything becomes routine and "untragic." There's endless speculation and rumor — about the course of the war, whether the commandant is coming, what the other camps are like, and the threat of transport "to the east." Most fascinating of all, Koker records what might be the only eye-witness written account by an inmate of a face to face encounter with Heinrich Himmler, and it's a fine example of the young Koker's power of observation, reflection, and superb writing, all under dreadfully dangerous circumstances. A sixty-page introduction introduces the larger context of the war in the Netherlands and Koker's family. Over eight hundred footnotes in the book elucidate the details of people, places, events, and Nazi policies. A final appendix recounts what little we know about how David Koker actually died, and also what we do know about the fates of many people mentioned in the diary.