Book Notes

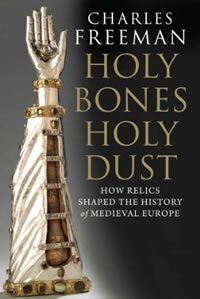

Charles Freeman, Holy Bones, Holy Dust; How Relics Shaped the History of Medieval Europe (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011), 306pp.

Charles Freeman, Holy Bones, Holy Dust; How Relics Shaped the History of Medieval Europe (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011), 306pp.

The cradle and cross of Christ. The milk of Mary and the rod of Moses. The right arm of John the Baptist, a tooth of Peter, and the head of Lazarus. These are just a few of the religious relics that included "virtually every kind of object" in medieval Christianity. Relics served many purposes for both kings and clerics. They were objects of prestige, forms of patronage, talismans of power, and most certainly sources of immense profits. Most of all, though, they were a "gateway to the supernatural" (269) that mediated a tenuous relationship between a holy God and sinful humanity. Relics were an avenue to intercession in heaven, a hope for the miraculous on earth, and nothing less than "public demonstrations of sacred power."

It would be hard to exaggerate the influence of relics in medieval life. Nonetheless, the obvious case against them was made by many people. "As the sun does not need the lamplight," wrote Basil of Caesarea, "so also the church of the congregation can do without the remains of the martyrs. It is sufficient to venerate the name of Christ." Others observed that people enjoyed a direct relationship with God and didn't need mediating objects. Some supported relics in principle but were appalled by their practice — uncritical enthusiasm, hocus pocus, exploitation of the poor, and so on. Even the Fourth Lateran Council of 1215 worried that relics were being "exposed for sale and exhibited promiscuously" (143). In turn, these objections provoked even more sophisticated (and tenuous) defenses of the role of relics.

By the sixteenth century complex forces produced a virulent iconoclasm among the Protestant reformers. Specific responses varied according to each town, but by the 1520s there began a systematic destruction of relics, images, sculptures, altar pieces and wood panels. In Basel in 1529 town authorities destroyed relics in a public bonfire. To avoid chaos, other towns closed churches and hired craftsmen to disasemble the many forms of "sacred sacrilege." John Calvin wrote his Treatise on Relics in 1543. Renaissance thinkers questioned the whole concept of the miraculous. The Catholic church pushed back, of course, in the counter Reformation. Relics were far too deeply embedded in the practices of the ordinary laity to be erased. After all, handkerchiefs and aprons that had been touch by the apostle Paul healed the sick and cast out evil spirits (Acts 19:11–12).